Nutrition Impact and Positive Practice (NIPP) Circles

By Vimbai Chishanu, Okello Aldo Frank, Sarah Ibrahim Nour, Hatty Barthorp and Nikki Connell

By Vimbai Chishanu, Okello Aldo Frank, Sarah Ibrahim Nour, Hatty Barthorp and Nikki Connell

Vimbai Chishanu is a former nutritionist with GOAL Zimbabwe

Okello Aldo Frank is a nutritionist with GOAL South Sudan

Sarah Ibrahim Nour is a nutritionist with GOAL Sudan

Hatty Barthorp is Nutrition Advisor with GOAL

Nikki Connell is a former Nutrition Advisor with GOAL

Location: South Sudan, Sudan and Zimbabwe

What we know: In communities where undernutrition is common, there are many contributory factors related to food diversity and social, care, health or environmental health practices. Integrated multi-sectoral approaches to tackle undernutrition are needed but are a challenge to implement and sustain.

What this article adds: GOAL has devised an integrated, community nutrition approach to malnutrition that centres on community ownership, using local available resources and capacity. It involves close coordination between sectors, such as WASH and health. The Nutrition Impact and Positive Practice (NIPP) circle method has been well received amongst communities in South Sudan, Sudan and Zimbabwe. The focus of activities is on behaviour change, micro-gardening and cooking demonstrations led by community members. Broad admission criteria are used that prioritises those most at nutritional risk. A simple longitudinal monitoring system tracks progress; data so far show promising results. The approach has successfully engaged volunteers without the use of unsustainable incentives. There is a strong sense of individual and community ownership of the project.

The Nutrition Impact and Positive Practice (NIPP) circle methodology is a community nutrition approach to address problems of malnutrition sustainably by supporting communities to help themselves, using locally available resources and low-cost technologies. It can be used as a community based alternative for the treatment of mild or moderate acute malnutrition and as a preventative tool to reduce risk of new episodes of acute malnutrition from occurring. Thus it should help contribute to a reduction in stunting and low birth weight, caused by malnutrition related intrauterine growth retardation.

The Nutrition Impact and Positive Practice (NIPP) circle methodology is a community nutrition approach to address problems of malnutrition sustainably by supporting communities to help themselves, using locally available resources and low-cost technologies. It can be used as a community based alternative for the treatment of mild or moderate acute malnutrition and as a preventative tool to reduce risk of new episodes of acute malnutrition from occurring. Thus it should help contribute to a reduction in stunting and low birth weight, caused by malnutrition related intrauterine growth retardation.

NIPP circles are used in community contexts where undernutrition (in any section of the demographic) is common and where a lack of dietary diversity and inappropriate social, care, health or environmental health practices have been identified as contributory factors in causing malnutrition. NIPP circles aim to improve the nutrition security and care practices of households (HH’s) either affected by, or at risk of suffering from, malnutrition, through participatory nutrition/health education and dietary diversity promotion. The design engages with both males and females to highlight issues surrounding and affecting nutrition, which both enhances the role of men in childcare and supports females to engage in positive practices.

How NIPP circles work

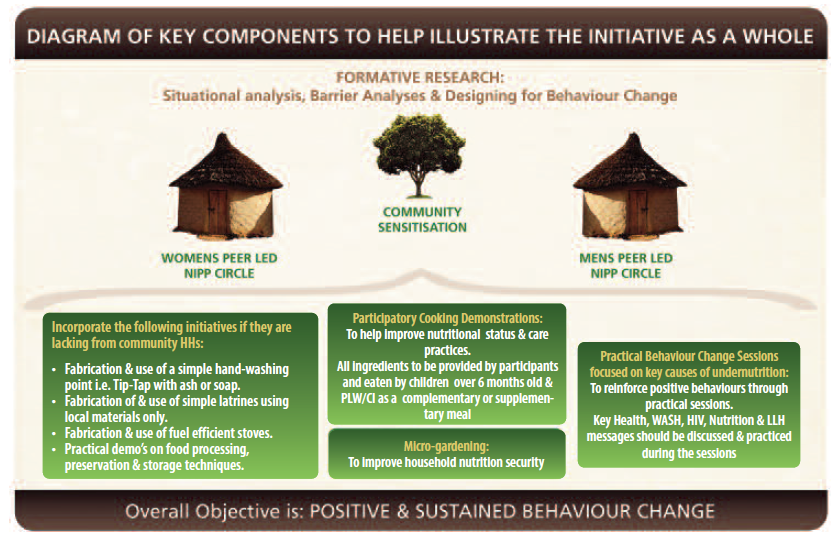

The overall approach is reflected in Figure 1. NIPP circles are gatherings of males and females separately within a community. A “macro circle” is broken down into three separate circles: parallel male and female circles of representatives of targeted households, and a third circle for key community figures (traditional healers, influential religious figures, respected elderly, etc). The community circle is only undertaken at the outset of the project to maximize awareness and transparency of what the project aims to achieve. Over a period of usually12 weeks, the members of the male and female circles meet on a regular basis for 2-3 hours, at multiple junctures during the week (decided by themselves) to share and rehearse positive behaviours. The circles aim to facilitate knowledge and skills sharing of both men and women using group discussions, practical exercises and positive reinforcement to help families adopt sustainable, positive behaviours. There are three main areas of focus: (a) Behaviour Change Communication and Counselling - for improved awareness and practice (b) Micro-gardening - for improved nutrition security and (c) Cooking demonstrations for improved feeding and care practices. This allows the project to address many of the underlying causes of malnutrition (see Box 1 for more details).

Figure 1: Diagram of key components of the NIPP circles approach

Box 1: NIPP areas of focus

The Behaviour Change sessions use findings from formative research (including barrier analyses) to focus on pre-identified key causes of malnutrition and reinforce positive behaviours through engaging, practical sessions. Included within these sessions are demonstrations on how to make a simple, replicable household hand-washing point, drying rack and latrine (if not already in situ), construction and use of fuel efficient stoves and practical demonstrations on food processing, preservation and storage techniques.

Micro-gardening aims to improve household dietary diversity, but also has a focus on food preservation and processing, which helps to improve food/nutrition security during lean seasons, as well as periods when foods are more abundant.

Cooking demonstrations for improved feeding and care practices are done through practical cooking of high energy, nutrient dense foods. All foodstuffs and equipment are provided by the participants and are then eaten by malnourished children/pregnant and lactating women and/or chronically ill, acting as a supplementary meal. Cooking demonstrations are carried out on fuel-efficient stoves built from locally available materials and participants are subsequently taught how to make their own for home use.

There are a number of target groups that may be admitted; the highest risk individuals are prioritised (see Table 1). Admission may include children discharged from outpatient SAM treatment, children with MAM, malnourished/at risk infants < 6 months of age, malnourished pregnant or lactating women, and families with chronic illness. Caregivers who wish to participate irrespective of a child’s nutritional status may also do so, on the basis that young women or mothers whose children are not malnourished but have less experience and an appetite to learn will benefit from participating in the interests of preventing malnutrition. Malnourished children may be admitted based on MUAC, weight for height % of the median (WHM) or weight for age (WA) criteria, to encourage inclusivity (e.g. referral from growth monitoring clinics). In practice, most children are admitted using MUAC. For practical purposes and due to the stronger association of MUAC with mortality risk, only MUAC is used as an anthropometric discharge criterion.

| Table 1: Admission and discharge criteria for female circles | |

|

Admission criteria to female circles |

Discharge criteria for female circles |

|

All children recently discharged cured from OTP* |

MUAC ≥12.5 cm for children at the end of the NIPP Circle cycle and Carers pass the post-test assessment (includes theory and practical elements) |

|

Families with children with moderate MN: Children 6-59m with MUAC 11.5cm - <12.5cm Children 6-59m with WHM <80% referred from a health facility Children 6-59m with WA <80% or growth faltering on their ‘road to health’ chart Infants 2-6m with MUAC <11cm with appetite Infants <2m visibly thin but with appetite |

MUAC ≥12.5 cm for children 6-59m; MUAC ≥11 cm for infants 2-6m; improved nutritional status for infants <2m on ‘road to health’ charts (verified at health facility) at the end of the of NIPP Circle cycle and Carers pass post-test assessment (includes theory and practical elements) |

|

Malnourished pregnant or lactating mothers (MUAC <23cm – cut-offs may vary by country as per national guidelines) |

MUAC ≥12.5 cm Carers pass post-test assessment (includes theory and practical elements) |

|

Families with chronic illness (including HIV cases), families with twins or multiple births, families where the primary carers show a keenness to participate to improve their public health nutrition education (PHNE) knowledge |

Carers pass the pass post-test assessment (includes theory and practical elements) |

|

Defaulter criteria for female circles |

|

|

If the primary carer is absent for two sessions consecutively and the team are not able to trace her, the HH should be discharged from the Circle as a defaulter on the second session. Similarly, if they are able to trace her but she is not interested in returning, the HH should also be discharged as a defaulter on the second session. |

|

|

Non-responder criteria for female circles |

|

|

If the relevant discharge criteria have not been attained at the end of the Circle period, the HH can be discharged as a non-responder (NR). If their non-response is thought to be due to lack of adequate behaviour change, the HH should ideally be readmitted into the next Circle for a repeat cycle. If however, non-response is thought to be due to an underlying clinical condition, they should be referred to the nearest health facility for assessment |

|

|

Referral criteria to OTP or health facility - if referred, should be discharged from the NIPP circle |

|

|

1. Child 6-59m with MUAC <11.5cm, WH <70% or below 70% on their ‘road to health’ chart 2. Child with bilateral pitting oedema 3. Infant, child or adult not clinically alert and well 4. Malnourished infant or child with no appetite 5. Infants less than 6 months who are failing to thrive (diagnosed by plotting serial weight for age on road to health card) 6. Unexplained weight loss or static weight gain at the end of the Circle cycle with regular attendance |

|

MN: malnutrition; WHM: Weight for height % of the median; WA: Weight for age; MUAC: Mid upper arm circumference; NR: Non-responder; HH: household; OTP: Outpatient Therapeutic Programme * Includes children >59m.

The session structure provides an environment where members can discuss and learn about recommended practices and access peer support. NIPP circles are led by trained community volunteers (male and female) who are identified ‘positive deviants’ within their villages. These volunteers are positive role models whose households have a comparatively better nutritional status than the other households, despite their similar living and socio-economic conditions. Their knowledge of successful behaviours and practices are honed and transferred to households with under-nourished children or other ‘at risk’ groups. To maximise compliance and impact, sessions are designed to be fun, interactive and thus engaging through use of song, poetry, dance, role plays, games and drama.

The programme’s approach of using community solutions to address malnutrition makes it sustainable and low cost. It also brings to the fore the inter-sectoral links with water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH), health and agriculture, thereby addressing some of the core causes of malnutrition. The promotion of fuel efficient stoves results in the use of much less energy, saving household income and also helping to conserve the local environment and resource base.

The NIPP Circle model uses formative research including designing for behaviour change (DBC) frameworks with Barrier Analyses (BA) and survey and assessment data, to help identify specific causes of malnutrition and barriers and boosters to change. This allows programme teams to design evidence based activities for the circles, specific to the contexts they are working in, allowing the greatest impact to be achieved.

As the NIPP circle approach involves promotion of key nutrition, health, WASH and livelihood behaviours, the relevant Ministries of Health and Agriculture are key stakeholders in each country. These government partners, in addition to the GOAL sector staff in country, provide technical trainings to staff and volunteers, including MUAC screening, counselling and behaviour change techniques, construction and use of micro-gardens, construction and use of fuel efficient stoves, participatory cooking demonstrations, food preservation, processing and storage, tippy-taps1 (or alternative) and latrine construction. They also assist with monitoring and support to households to implement behaviour change and assist with data collection where workload permits.

In addition to close collaborations with government ministries, local CBOs and national NGOs have also been engaged to run NIPP circles, whereby financial outlay is purposefully kept to a minimum to encourage sustainability. In Sudan, the local NGO ‘WOD’ is piloting 47 NIPP circles in Kassala state and ALMANAR is piloting eight circles in Khartoum. In South Sudan, SMART, a local NGO, is working with GOAL to understand supervision mechanisms and to assist with anthropometric measurements and micro-gardens.

All elements of the programme – from visual aids to education approaches to fuel efficient stoves – have been well received. Despite apprehension by GOAL staff and partners, in most locations, families are happy to contribute the food for the cooking demonstrations undertaken in the female circles, which is very positive, as their individual outlay is no greater than that they would have invested in feeding their children/themselves, but as a collective is far more powerful. Running a project through community volunteers (with no financial incentives) has also been a success aided by a sensitive community approach, adequate dialogue and a limit to the investment of time needed; most lead volunteers only have to engage in a handful of circle cycles, to cover eligible neighbours. Support can then be relocated elsewhere to start up new circles.

Health centres are linked directly with the NIPP circles, with participants referred to health facilities for available services (illness – chronic or acute, ante-natal and peri-natal care, expanded programme on immunisation (EPI) and growth monitoring where appropriate). Outpatient therapeutic programme (OTP) discharges are referred to NIPP circles after their severe acute malnutrition has been resolved. This can be done in conjunction with supplementary feeding programmes (SFPs) or independently, as often the causes of malnutrition are far greater reaching than merely food insecurity alone.

Programme rollout

GOAL is rolling out the NIPP circles in South Sudan, Sudan and Zimbabwe:

- The first pilot was carried out in South Sudan in late 2011 and so far, 50 macro-circles have been set up in 2013 across four locations (11 in Agok in Abyei Administrative Area, 16 in Twic County in Warrap State and 23 in Baliet and Ulang Counties in Upper Nile State).

- GOAL began piloting the NIPP circle project in Sudan in late 2012 in Kutum, North Darfur where 20 circles have been implemented by GOAL, 47 circles through the partner Waad Organisation for Development (WOD) in Kassala State, and 8 circles through the partner Almanar in Khartoum State. To date, there have been 125 circles implemented across both country locations.

- The NIPP circle project also began in Zimbabwe in mid-2013 and at the end of 2013, 24 circles had been implemented in Zimbabwe in each of the districts of Hurungwe, Makoni and Nyanga, totalling 72 macro-circles. The Zimbabwe project has funding for 3 years through the DFID Global Poverty Action Fund (GPAF) grant and plans to complete 432 macro-circle cycles across the three districts by February 2016, whereby approximately 22,000 direct beneficiaries will have been reached.

Programme challenges

The main challenge that this project has faced across all locations is poor male participation in the circle activities, despite motivation from communities. This is starting to improve in Sudan where successful graduates are used to encourage other men to attend the circles and attendance certificates are provided after successful graduation. Since this project is a ‘no hand-out’ project, households themselves providing the necessary inputs, volunteer participation is a challenge in South Sudan. This is especially an issue if partner organisations working in the same areas have volunteer incentives (payments) as part of their approach. GOAL has identified non-material incentives used in some sites to further motivate volunteers, including volunteer recognition days, certificates for completing the training and engaging volunteers in other GOAL projects, such as female literacy programmes. Lastly, in Sudan the shortage of water can be a challenge in dry areas, so maximising yields during rain fed seasons is promoted with subsequent processing, preservation and storage being used to improve access to harvested produce during the lean seasons. This approach is combined with the promotion of household waste water use to water reduced sized micro-gardens during dry spells.

Programme monitoring

A longitudinal monitoring system has been designed to enable GOAL to monitor various outcomes, including anthropometric status of young children and PLW, care and feeding practices, micro-gardening, food use, hygiene-sanitation practices and HIV prevention awareness. A guiding principle has been to make the data collection realistic and as easily replicable by GOAL/partner field teams as possible. In Sudan, where two local NGOs are implementing, they are undertaking data collection. Data points are collected at baseline, upon graduation for all admissions, then 2 months, 6 months and 12 months post-graduation for a significant sample, which will help to provide a picture of the sustainability of different elements of the project. Graduation is based on admitted participants with MAM achieving improved anthropometric status, attaining a certain level of knowledge and demonstrating that they are using newly acquired practices at a household level. If admission is not based on MAM, participants still have to achieve the latter of the three requirements. If significant relapse is observed at a particular juncture post-graduation, the design of the project could feasibly be adapted to include one-off or short-term refresher sessions, to further cement positive behaviour change.

At the time of writing, we have verified results in Sudan and South Sudan at graduation only, whereby both countries have been affected by political and security associated access restrictions, delaying original implementation and support plans. Tables 1 and 2 outline a selection of the key findings from the database.

| Table 2: South Sudan results from female circles during 2013 | ||||

|

State/Area |

||||

|

Warrap State |

Abyei Admin-istrative Area |

Upper Nile State |

Upper Nile State |

Comments |

|

County/area |

||||

|

Twic |

Agok |

Baliet |

Ulang |

|

|

# Female circles opened |

||||

|

4 |

10 |

6 |

6 |

Results from female cirecles only have been highlighted in this table, as most data are collected from these groups. |

|

Date opened |

||||

|

May 2013 |

Feb – Aug 2013 |

June 2013 |

March 2013 |

|

|

# of admissions into female circles |

||||

|

29 (1 x PLW, 28 x children 6-59m)

|

97 (1 x 2-6m, 74 x 6-59m, 4 x OTP disch, 17 x PLW, 1 x other) |

60 (41 x 6-59m, 15 x PLW, 4 x other) |

47 11 x 6-59m, 23 x PLW, 3 x other) |

|

|

% graduating successfully (n)* |

||||

|

96.6% (28 success, 1 DEF |

56.9% (33 success, 22 DEF, 2 NR, 1 REF, 39 graduated datasets uncollected) |

66.7% (40 success, 13 DEF, 7 NR) |

57.4% (27 success, 4 DEF, 16 NR) |

In Agok, the circles suffered from high defaulter rates. Ulang’s relatively high NR rate may be attributable in part due to GOAL’s access to Ulang being compromised at times during the cycle, so the requisite support was not aways available. |

| % of children 6-59m admitted with a MUAC <12.5cm reaching gradulation with a MUAC >12.5cm & PLW admitted with MUAC <23cm reaching graduation with MUAC >23cm | ||||

|

96.6% (27 of 28 children admitted on MUAC & 1 of 1 PLW achieved MUAC targets upon graduation)

|

60.4% (of 58 full datasets, 32 of 53 children admitted on MUAC achieved MUAC cut-offs upon graduation, no complete PLW data collected) |

66.0% (26 of 41 children admitted on MUAC & 11 of 15 PLW achieved MUAC targets upon graduation) |

59% (6 of 11 children admitted on MUAC & 20 of 33 PLW achieved MUAC targets upon graduation) |

Of those admitted based on MUAC, results for non-sucesses were as follows: Twic: 6-59m 1 x DEF Agok: 2-6m 1 x no graduation data at the point of collation, 6-59m 21 x no graduation data, 19 DEF and 2 NR. PLW 17 x no grad’ data Baliet: 6-59m 11 x DEF and 4 x NRs, PLW 2 x DEF and 2 x NRs. Ullang: 6-59m 1 x DEF and 4 x NRs, PLW 1 x DEF and 12 x NRs Note: only one infant was included 2-6m with a MUAC <11cm but with an appetite in Agok, but graduation data was not available at the time of writing. |

|

% eating produce from the microgarden at graduation |

||||

|

92% |

97.2% |

100% |

56.8% |

No baseline was collected as most HH’s didn’t have microgardens prior to NIPP Circle support. The % in Ulang was lower than the other sites because some of the participants still chose to sell the produce in the market rather than eat it in the household, despite advice to prioritise HH consumption. Due to GOAL’s access to Ulang being compromised at times during the cycle, support to beneficiaries to encourage household consumption was limited. GOAL is working to address the issue of access for future circles. |

|

% showing improvement in knowledge on causes of malnutrition |

||||

|

89.3% improvement in knowledge (from 0% to 89.3%)

|

30.13% improvement in knowledge (from 67% to 97%) |

50% improvement in knowledge (from 50% to 100%) |

24.3% improvement in knowledge (from 61.7% to 86.1%) |

Baliet/Ulang recruited staff immediately prior to the start-up of NIPP circles, so their knowledge on the topics was more limited than other sites. Now they have undergone training, this should improve moving forward. Baliet/Ulang NIPP circle volunteers spent a lot of time on the micro-garden element, so less time was spent on some other topics. This will be rectified in future circles to ensure sufficient time is spent on all aspects. |

|

% knowing how to make high-energy porridge at baseline and at graduation |

||||

|

0.0% baseline, 92.3% graduation |

51.6% baseline, 100% graduation |

71.7% baseline, 100% graduation |

59.6% baseline, 93% graduation |

Note: Graduation percentages are based on total no. of discharges less defaulters, as graduation data could not be collected for those having defaulted from the circle cycle |

|

% with latrine with evidence of use in the homestead at baseline and graduation |

||||

|

3.5% baseline, 7.4% graduation |

0.0% baseline, 14.3% graduation |

3.3% baseline, 12.8% graduation |

2.1% baseline, 2.4% graduation |

GOAL’s WASH staff were unable to participate fully in this initial round of NIPP circles due to staff absences and without technical support, often latrine pits collapsed prior to completion of the latrine. In the future adequate WASH support is planned which will allow beneficiaries to observe several alternatives for latrine construction. |

|

% with handwashing facility and evidence of use in the homestead at baseline and graduation |

||||

|

0.0% baseline, 10.7% graduation |

47.9% baseline 82.9% graduation |

0.0% baseline 21.3% graduation |

2.13% baseline 7.1% graduation |

As per the above, there was inadequate WASH support provided during this round of NIPP circle cycles. Uptake of households willing to construct and use handwashing facilities in the homestead in Agok however was higher due to the beneficiaries largely being Muslim, where handwashing is an inherent part of their lifestyle. |

DEF: Defaulter; NR: Non-responder *Successful graduation includes achieving a MUAC 12.5cm or greater if aged 6-59 months/a MUAC 23cm or greater when PLW, in addition to passing a post-test which includes verifying key behaviour changes through home visits. To successfully graduate, all discharge criteria – target MUAC, knowledge attainment and practice demonstration – must be met.

| Table 3: Sudan results from female circles during 2013 | |||

|

State/Area |

|||

|

North Darfour |

East Sudan |

Khartoum |

Comments |

|

County/Area |

|||

|

Kutum |

Kassala |

Mayo |

|

|

# Female circles opened |

|||

|

10 |

47 |

8 |

|

|

Date opened |

|||

|

March 2013 |

April and July 2013 |

March 2013 |

|

|

# and type of admissions into female circles |

|||

|

145 (78 x 6-59m, 54 x OTP discharges, 2 x PLW, 2 x other) |

703 (13 x <6m, 565 x 6-59m, 70 x OTP, 55 x PLW) However, only 176 cases were follwed up and thus have graduation data |

97 (although only 2 gps, total of 28 members) had graduation data collected by end of 2013) |

Due to an omission by the partner in Khartoum & an oversight of GOAL, unfortunately only a small sample of admitted cases were followed up, not realising that ALL cases should be followed up at baseline and graduation and the smaller sample selected for longitudinal follow-up at 2m, 6m and 12m post graduation. |

|

% graduating successfully* |

|||

|

80% (116 success, 27 NRs, 1 DEF, 1 referral) |

92.6% (136 sucess, 14 NRs)

|

100% (28 success) |

|

|

% of children 6-59m admitted with a MUAC <12.5cm reaching gradulation with a MUAC >12.5cm & PLW admitted with MUAC <23cm reaching graduation with MUAC >23cm |

|||

|

81.2% (63 of 78 children admitted on MUAC and 2 of 2 PLW achieved MUAC targets on graduation. Also,of the OTP referals (admitted irrespective of MUAC) of the 54 admitted, 36 had a MUAC <12.5cm, 30 reached grad’ with a MUAC >12.5, 5 did not & 1 defaulted = 85.7%) |

94.7% (136 of 137 children admitted on MUAC and 8 of 15 PLW achieved MUAC targets on graduation. Also, 5 of 5 infants were admitted on MUAC <11cm and achieved a MUAC of >11 upon graduation, plus of the OTP referrals (admitted irrespective of MUAC) of the 20 admitted, 19 had a MUAC <12.5cm, 14 reached graduation with a MUAC >12.5cm = 73.7% |

100.0% (12 of 12 children admitted on MUAC achieved MUAC targets on graudation. Also, of the OTP referrals (admitted irrespective of MUAC) of the 15 admitted, 6 had a MUAC <12.5, all 6 greached graduation with a MAUC>12.5 = 100%) |

Of those admitted based on MUAC, results for non-successes were as follows: Kutum: 6-59m: 14 x NRs and 1 x referral Kassala: 6-59m: 1 x NR and PLW: 7 x NRs Mayo: none |

|

% eating produce from the microgarden at graduation |

|||

|

79.5% |

100.0% |

60% |

The % in Khartoum was lower than the other sites, but is expected to be even lower in other circles because the beneficiaries are in an internally displaced people (IDP) camp, with little access to land and limited water. Almanar (partner community based organisation) is working to address the issue of access for future circles. They have begun to pilot keyhole gardens and investigate alternative options to improve HH dietary diversity through improved market access, potentially replacing the micro-gardening element with an alternative livelihood activity |

|

% showing improvement in knowledge on causes of malnutrition |

|||

|

60.5% improvement in knowledge (from 33.3% to 93.8%) |

92.9% improvement in knowledge (from 1.1% to 100%)

|

49.5% improvement in knowledge (from 50.5% to 100%) |

|

|

% knowing how to make high-energy porridge at baseline and at graduation |

|||

|

15.9% baseline, 95.9% graduation |

1.1% baseline, 98.9% graduation |

36.1% baseline, 100% graduation |

|

|

% HH reporting functioning latrine with evidence of use in the homestead at baseline and at graduation |

|||

|

68.3% baseline, 96.6% graduation |

60.0% baseline, 82.3% graduation |

96.8% baseline, 100% graduation |

The baseline was higher in this programme and programme support for the hygiene and sanitation element of this project was strong. |

|

% with handwashing facility and evidence of use in the homestead at baseline and graduation |

|||

|

37.8% baseline, 97.3% graduation |

5.7% baseline, 75.7% graduation |

72.2% baseline, 100% graduation |

|

*Successful graduation includes achieving a MUAC 12.5cm or greater if aged 6-59 months/a MUAC 23cm or greater when PLW, in addition to passing a post-test which includes verifying key behaviour changes through home visits. To successfully graduate, all discharge criteria – target MUAC, knowledge attainment and practice demonstration – must be met.

Project costs

As the Zimbabwe project has stand-alone funding, it is more straightforward to estimate beneficiary cost (Sudan and South Sudan projects have a number of funding sources that complicate costing). Costings are based on the projected plans for incremental rollout over a three year period, which will see ~72 circles each running for 12 weeks, completing 432 cycles in different villages across three districts. The costs cover three months of pre-implementation surveys, formative research, activity planning and session designs, plus three months of post project evaluations and review. With an average of between 10-15 male and 10-15 female participants per cycle, these direct beneficiaries will amount to an average of 10,800 men and women plus a further 10,800 from the same households (usually children), where the average HH size in Zimbabwe is 4.3. Thus direct beneficiaries would amount to no less than 21,000 individuals. The total project budget is £1.4 million. Thus a conservative calculation of the cost per beneficiary (as we have only considered the core direct beneficiaries) would amount to ~£67/person. At a later stage, we will be able to take into consideration success rates. But given that the project aims to achieve sustained behaviour change, tackling a broad range of contributory causal factors, at this early stage, this is deemed an effective use of money in the fight against both acute and chronic forms of malnutrition.

Lessons learnt

There have been many positive outcomes, some unexpected, from the NIPP circle project. These can be used to strengthen interventions moving forward. For example, in one location in South Sudan, the circle members set up their own small village savings and loans scheme independently of GOAL (as they had previously been exposed to such a scheme). The savings were used to buy subsequent cycles of seeds, as many varieties available to them were hybrid and thus not self-regenerating. In another site in South Sudan, one of the male circles requested that they be tasked with the practical construction and maintenance of the micro-gardens instead of their wives, as part of role-sharing between themselves and their spouses. This is particularly attractive as we are conscious of the ‘do no harm’ element of the project and do not wish to overburden HH members, particularly mothers, with additional tasks that might negatively impact other positive practices. We have witnessed the significant role grandmothers play in family nutrition. Although the NIPP Guidelines outline that female circles should include female primary carers and female elders, the inclusion of mother-in-laws and grandmothers had been somewhat overlooked during the initial start-up of NIPP circles. In the future, these influential groups will be explicitly invited to join the female circles, either for all sessions, or if regular attendance is not possible, particularly when IYCF practices are being discussed.

On the negative side, GOAL have experienced problems in a number of field sites, whereby poor coordination between partner NGOs has resulted in the promotion of non-NIPP projects using different forms of volunteer incentivisation (either financial, food or non-food items) leading to difficulties in compliance for the NIPP project that works through true volunteers. Naturally, it will be demotivating for a NIPP volunteer to learn that ‘volunteers’ in other projects are receiving monetary or material incentives when they are not. Given that GOAL has striven to design a sustainable and replicable community based project, the provision of non-sustainable incentives would undermine this whole ethos.

For all implementing GOAL support teams, it has been particularly interesting to facilitate a project that seeks to address malnutrition through an integrated and multi-sectoral community based approach, using close coordination between sectors. In addition, it has been shown that it is possible successfully to incentivise volunteers through volunteer recognition days, group photographs displayed in the community and regular field visits to support volunteers. The removal of commonly used financial or ‘gift’ incentivsation means that not only is there a far greater sense of individual and community ownership of the project, ensuring that only people who really want to improve their quality of life participate in the circle cycles, but that local partners, national NGOs and the Ministry of Health would in theory all be able to run the project longer term at minimal cost. So far the project has proven more successful in rural areas than urban areas, indicating that a modified approach may be needed for urban contexts.

For more information, contact: Hatty Barthorp, GOAL, email: hbarthorp@goal.ie, Mutza Dzimba (Zimbabwe programme), email: mdzimba@zw.goal.ie, Frank Okello (South Sudan programme), emails: ofrank@ss.goal.ie and Sarah Ibrahim Nour (Sudan Programm), email: sibrahim@sd.goal.ie

For more information, contact: Hatty Barthorp, GOAL, email: hbarthorp@goal.ie, Mutza Dzimba (Zimbabwe programme), email: mdzimba@zw.goal.ie, Frank Okello (South Sudan programme), emails: ofrank@ss.goal.ie and Sarah Ibrahim Nour (Sudan Programm), email: sibrahim@sd.goal.ie

1Tippy-taps are an easily constructed, small-scale hand washing points for households, using locally available and accessible materials.