The Coverage Project: a national partnership for evaluating CMAM services in Nigeria

By Maureen Gallagher, Saúl Guerrero, Ifeanyi Maduanusi and Diego Macías

By Maureen Gallagher, Saúl Guerrero, Ifeanyi Maduanusi and Diego Macías

Maureen Gallagher is the Senior Nutrition & Health Advisor Action Against Hunger US based in New York. She is a public health specialist with an MSc in Social Policy and Planning specialising in health policy. She has been working in nutrition programming for the last 15 years in Niger, East Timor, Uganda, Chad, DRC, Burma, Sudan and Nigeria.

Maureen Gallagher is the Senior Nutrition & Health Advisor Action Against Hunger US based in New York. She is a public health specialist with an MSc in Social Policy and Planning specialising in health policy. She has been working in nutrition programming for the last 15 years in Niger, East Timor, Uganda, Chad, DRC, Burma, Sudan and Nigeria.

Saul Guerrero is Director of Operations at Action Against Hunger (ACFUK). Prior to joining ACF, he worked for Valid International Ltd. in the research, development and roll-out of CTC/CMAM. He has worked in over 20 countries in Africa and Asia.

Saul Guerrero is Director of Operations at Action Against Hunger (ACFUK). Prior to joining ACF, he worked for Valid International Ltd. in the research, development and roll-out of CTC/CMAM. He has worked in over 20 countries in Africa and Asia.

Ifeanyi Maduanusi is a Programme Quality and Accountability Technical Advisor for Action Against Hunger in Nigeria. He led the implementation of most the SQUEACs while he worked as CMAM Deputy Programme Manager for the Coverage Project

Ifeanyi Maduanusi is a Programme Quality and Accountability Technical Advisor for Action Against Hunger in Nigeria. He led the implementation of most the SQUEACs while he worked as CMAM Deputy Programme Manager for the Coverage Project

Diego Macías is a Learning Officer for ACF, working on learning outcomes from coverage programmes, including data analysis and qualitative assessments.

Diego Macías is a Learning Officer for ACF, working on learning outcomes from coverage programmes, including data analysis and qualitative assessments.

The authors would like to thank the participating Federal and States’ authorities, health workers and communities for their commitment to CMAM, support and active participation throughout the Coverage Project. Thanks also to the Coverage Monitoring Network for their technical support. Thank you to UNICEF, Save the Children, Valid International and Centre for Communications Programme in Nigeria for their collaboration as partners of the consortium. The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of the Children’s Investment Fund Foundation (CIFF) for their support to the Coverage Project and CMAM in Nigeria.

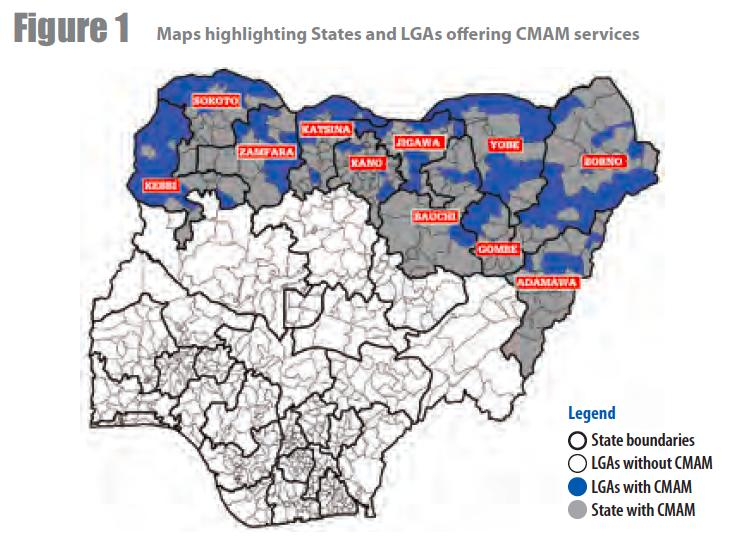

The Severe Acute Malnutrition (SAM) burden in Nigeria is known to be amongst the highest in the world, with over 10% of the global burden, resulting in an estimated 2 million children affected. Since 2009, the Government of Nigeria, with the support of UNICEF, started tackling the problem by piloting Community-based Management of Acute Malnutrition (CMAM) in two Local Government Areas (LGAs), one in Kebbi State and the other in Gombe State. Since then, Nigeria has proven their strong commitment to the fight against SAM, with geographical coverage extending to 91 LGAs in 11 states of the country, including 642 health facilities, as presented in Figure 1. This has also been possible as partners and donors have supported federal and state Ministries of Health (MoH) to institutionalise SAM management as part of regular routine health services. More than 1,000,000 children received treatment between 2009 and mid-2015.1

A large component of this scale up has been possible due to a strong partnership launched between the Children’s Investment Fund Foundation (CIFF), UNICEF and the Government of Nigeria (GoN) in 2013 (see article in this issue of Field Exchange). This also generated the opportunity for comprehensive evaluation and learning about progressively scaling up CMAM services. As a result, another partnership - for assessment and learning of coverage - was formed. ACF, Save the Children and Valid International worked together with UNICEF and MoH to design the Coverage Project, a collaboration in support of evaluation of SAM services funded by CIFF. The project included two key components: 1) Assessment of coverage and 2) Community Mobilisation Pilot Project. The findings, recommendations and lessons learned from the project were brought together in a Learning Review document.2 Both project components were undertaken in close consultation and collaboration with the MoH and UNICEF.

The Coverage Project in Nigeria

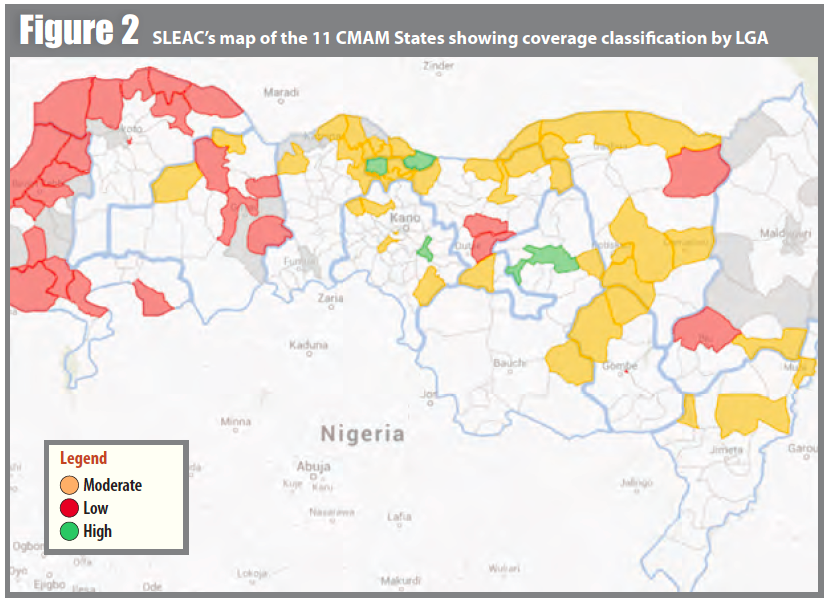

The Assessment of Coverage component was implemented in two phases. First, a SLEAC3 was conducted by Valid International to classify coverage of 71 of the 91 LGAs implementing CMAM programming between October 2013 and March 2014, providing an overall picture of the coverage levels of CMAM throughout a high proportion of LGAs. The SLEAC offered a clear view on both the geographical and the direct coverage of CMAM in the region, identifying regions, especially in the northwest, where efforts were needed most. The results are presented in Figure 2.

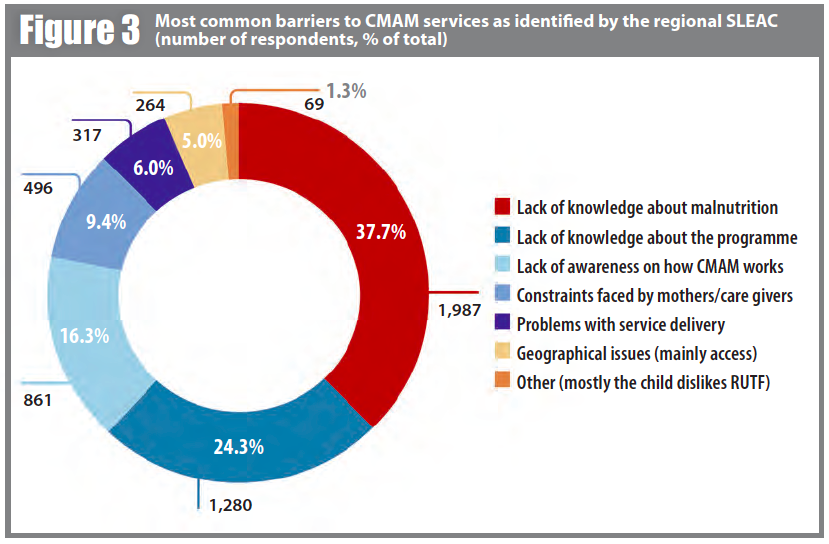

A national workshop was held with key stakeholders to review findings and identify locations for the second phase of this component. More in depth information on coverage was obtained through 12 Semi Quantitative Evaluation and Access of Coverage (SQUEAC) surveys which were implemented by ACF and Save the Children, with support of the Coverage Monitoring Network (CMN) and Valid International. A practical training was conducted in March 2014, when the first survey was jointly done. Then, Save the Children conducted five surveys in the northwest and ACF conducted six surveys in the northeast. All surveys were completed by December 2015. Key findings of the more in depth analysis provided by the SQUEACs on barriers to access are presented in Figure 3.

Based on SLEAC and SQUEAC findings, which clearly revealed the lack of awareness about SAM and of services available as common barriers to access across states, the Community Mobilisation Pilot Project was developed in partnership with the Centre for Communication Programmes Nigeria (CCPN) in June 2014. The pilot approach for a sensitisation campaign was developed and tested in two LGAs in Sokoto State – Goronyo and Sokoto South LGAs (both had SLEACs conducted in November 2013 and one SQUEAC was conducted in Goronyo in March 2014). The choice of State and LGAs was discussed and agreed between ACF, Save the Children and UNICEF based on common criteria. UNICEF then supported the visit and introduction of CCPN to Sokoto State. Workshops were held with key stakeholders in the State to explain the goals of the initiative and engage participants in the design of the awareness strategy and tools. The campaign was implemented by Hikima Community Mobilisation and Development Initiative (HCOMDI), a local grassroots organisation. During the four months of the campaign (October 2014 - Jan 2015), over 110 community dialogues, 300 household visits and active case-finding activities were delivered with the support of community volunteers and involvement of key stakeholders of the outreach area; about 32,000 people are estimated to have been reached during the campaign. In order to measure the impact of the approach and compare it between LGAs, end line SQUEACs were conducted in both LGAs in February 2015. The results of the pilot project are presented in Box 1.

Box 1 - Community mobilisation pilot project results

- Admissions. In both LGAs, the admissions between September and December 2014 were higher in proportion to total yearly admissions compared to the earlier part of the year (41% in Goronyo and 40.6% in Sokoto South). Seasonality did not affect admission rates in this case, as the lean season is between May and August, which would have led to higher admissions during that part of the year rather than Sept- Dec and/or Jan-April.

- Barriers to access. The study demonstrated that barriers can be positively tackled. In Goronyo, awareness related barriers (about malnutrition, the ongoing programme and/or how the programme works) accounted for 71% of the reasons provided by all non-covered cases for not accessing services prior to the campaign. This proportion reduced to 48% after the campaign. Whilst this is based on a small sample, it does suggest that targeted campaigns can have a measurable impact on awareness related barriers. As a result of the decrease in awareness related barriers reported, two other key barriers were more widely reported – quality of service delivery (including stock outs) and constraints faced by the mother (opportunity costs, money for transport). This suggests that addressing awareness is effective yet not sufficient to increase coverage alone as other barriers become more prominent.

- Coverage. Estimated coverage levels did not significantly change between baseline and endline. Sokoto South’s level indicated slight improvement in comparison to the SLEAC (below 20%), whereas Goronyo (14.7%) did not reflect meaningful changes4. This is likely to have been due to a combination of wide confidence intervals but also because other barriers became more prominent, indicating that all barriers need to be addressed at the same time to result in increased coverage.

A final workshop was held mid-March 2015 in order to present the SQUEAC and pilot project results, as well as to engage key stakeholders on next steps and recommendations in order to strengthen key findings. Directors of Primary Health Care (PHC), State Nutrition Officers (SNO) from the 11 states and FMOH Nutrition Department members attended the workshop and shaped key recommended actions. A summary of actions proposed by the Directors, SNOs, and other partners to tackle the key challenges revealed by the coverage assessments is presented in Box 2.

Box 2 - Key actions proposed by stakeholder to tackle main barriers to increasing coverage of CMAM in Northern Nigeria

1) Innovative awareness-raising method

- Diversify groups and locations for meetings: community dialogues, social, town hall, compound and household meetings

- Diversify key stakeholders involved : include community & religious leaders, traditional birth attendants (TBAs), school teachers and students

- Use of community based organisations (CBOs) and existing support groups

- Use of media, mobile phones/SMS, IEC (information, education & communication) materials to sensitise the public

- Community action-oriented activities such as: local dramas, local songs, food demonstrations, community nutrition champions

2) Resource learning to institutionalise CMAM and scale up

- Evidence-based advocacy and sensitisation to engage philanthropists, policy makers, and first ladies to support CMAM, at all levels

- Include nutrition and CMAM into state budget / Costed Nutrition Plans and timely release of funds

- Engage in public-private partnership to support nutrition and CMAM

- Collaborate with other projects such as Millennium Development Goals Fund projects and Maternal Child Health initiatives

- Reactivate and strengthen committees for food and nutrition for resource mobilisation

3) Strengthen adherence to national protocol

- Increasing number of health workers trained and refresher training on national protocol and its application

- Continuous training of community volunteers on detection and referral

- Routine and supportive supervision by the State MoH teams

- Engage trained and skilled community health extension workers for management of SAM

4) Improve data quality

- Strengthen capacity of service providers on data collection, management and analysis and M&E systems

- Timely supportive supervision, on-site monitoring, dissemination and feedback at all levels (consider the use real time monitoring through smart phones)

- Verification and validation of data, including data quality assessments

- Provision of a central databank for nutrition programmes

5) Strengthen community volunteer (CV) network

- Training and retraining of CVs with regular meetings and experience sharing with health workers

- Strengthen CVs to support outpatient activities in the communities (screening, tracing of defaulters, referral and home visits)

- Performance awards for motivated and engaged CVs

- Motivation and incentives schemes should be considered for CVs

Lessons learned for SAM scale up in Nigeria

The Learning Review - SAM Management in Nigeria: Challenges, Lessons & the Road Ahead5 - outlines the current state of SAM in Nigeria, provides the detailed in depth analysis and results of the coverage assessment, the outcomes of the pilot project and the recommendations for improving SAM in Nigeria. It was revised and agreed on by all partners of the project. Some of the key lessons learned from the Coverage project, pulled together from multiple streams – including the comprehensive SAM context analysis, coverage assessments, pilot project and workshop inputs – and reflected in the learning review are outlined below.

- Two out of every three SAM cases in North Nigeria are not accessing treatment. Recent surveys carried out by the SLEAC of 2013-14 suggest that CMAM services across the 11 northern states are reaching an estimated 36.6 per cent of SAM cases.

- SAM management services are located in states with the greatest need, but the spread of services within those states remains limited. Most states only offer SAM treatment services in less than half their local government areas, which considerably reduces the capacity to deliver services to the targeted population.

- The expansion of CMAM services has not been matched by an increase in trained and available staff. Training and follow up of an increased number of health workers and CVs has the potential to increase the quality of services delivered both through the availability of adequate numbers of personnel and the improvements in treatment, screening, referral and follow-up activities. For instance, evidence from SQUEAC assessments show that some inconsistencies exist with regards to CMAM protocols at times of cured discharges. Revising modes of delivery and extending staff training can also improve quality of care.

- Making CMAM services available does not make them accessible. The data shows that the coverage in areas with a higher number of facilities, or smaller geographical or demographic catchment areas, is not necessarily higher. Efforts to improve infrastructural and logistic obstacles, such as stock outs of ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF), are necessary. Stock outs were especially problematic in Goronyo with SLEAC and SQUEAC surveys showing these lasting more than two months in late 2013/early 2014. Examples of approaches to address stock outs could include an increase in LGA and health facility based stocks of RUTF. Furthermore, a doubling or tripling of rations could be considered as a way of reducing the numbers of visits and time spent traveling for caregivers.

- Awareness about SAM, the existence of CMAM and the way it functions can and must be improved. A community mobilisation strategy should be designed to sustain wider sensitisation campaigns involving local populations and empowering local and state authorities. Recent evidence suggests that increased awareness helps to increase admissions to CMAM. Moreover, in the long term it might help improve service delivery itself.

- There is room for improving the quality of SAM management information and data. The scale up of CMAM services requires strong information systems that can provide reliable and timely information to decision makers at LGA, state and federal levels. Improving the quality of available information must be prioritised and the expansion of existing pilot models (including Rapid SMS) considered. Strong commitments to capacity building, training and resource allocations are necessary to improve the performance of CMAM service delivery; this can only happen via a coordinated mechanism between key nutrition stakeholders in country.

The Coverage project and a key output in the form a learning review has been a positive joint partner initiative to work in support of the GoN to further advance and succeed in their fight against SAM. Key next steps will involve close follow-up of application of recommendations and monitoring of coverage for further strengthening CMAM in Nigeria.

For more information, contact: Maureen Gallagher, email: mgallagher@actionagainsthunger.org

1 ACF (2015). SAM Management in Nigeria: Challenges, Lessons & the Road ahead

2 Learning Review. SAM Management in Nigeria: Challenges, Lessons & the Road Ahead. ACF International, ACF Nigeria. March 2015. Available at: http://www.coverage-monitoring.org/resources-library/

3 Simplified LQAS (Lot Quality Assurance Sampling) Evaluation of Access and Coverage

4 The first programme SQUEAC took place precisely in Goronyo and its coverage estimate was 14.3%. In the SLEAC in late 2013, the LGA had an estimated coverage of 0.5%.

5 See footnote 2