Management of SAM in the Philippines: from emergency-focused modelling to national policy and government scale-up

By Aashima Garg, Anthony Calibo, Rene Galera, Andrew Bucu, Rosalia Paje and Willibald Zeck

Aashima Garg is Nutrition Specialist based in UNICEF New York. At the time of writing, she was Nutrition Manager with UNICEF Philippines leading the nutrition emergency and regular programmes. She has over 11 years’ of experience in the area of public health nutrition programming across south Asia.

Anthony P. Calibo MD, DPPS is a Medical Specialist IV at the Family Health Office, Department of Health, Manila. He is the current Chair of the CMAM and IYCF National Technical working groups.

Rene Galera MD, MPH is a Nutrition Specialist with UNICEF Philippines.

Andrew Bucu MD, MPH is a SAM Management Scale Up Consultant, engaged by UNICEF Philippines.

Rosalie Paje MD, MPH is Division Chief, Preparedness Division, Health Emergency Management Bureau, Department of Health, Manila. She chaired the CMAM Technical working group from mid to end 2015.

Willibald Zeck MD, MA is Chief of Health and Nutrition Section, UNICEF Philippines.

The authors would like to acknowledge colleagues from the National Nutrition Council, Department of Health – Asec. Maria-Bernardita T. Flores, CESO II, Assistant Secretary of Health and Executive Director/Chair of the National Nutrition Cluster; Maria Lourdes A. Vega, Chief of the Nutrition Policy and Planning Division; Margarita D.C. Enriquez, Nutrition Officer II/IMO and Secretariat of the National Nutrition Cluster. Thanks also to Valid International for technical support in development of the National Guidelines, members of the National CMAM working group, and Christiane Rudert and Cecile Basquin from UNICEF East Asia and Pacific Regional Office.

Location: The Philippines

What we know: Access to essential health and nutrition services by the poor and marginalised in the Philippines is low, exacerbated by recurrent disasters and conflict. Malnutrition persists as an alarming concern in the country.

What this article adds: The emergency response to super-typhoon Haiyan in 2013 included successful, cluster-led programmes for treatment of severe acute malnutrition (SAM), but highlighted significant shortfalls in national policies, protocols, health system capacity, supplies and government buy-in.

Subsequently, national guidelines for the management of SAM were developed and adopted by the Philippine Government in a participatory, consultative process led by the Department of Health, with UNICEF technical support, expert and partners’ consultation, and SUN stakeholder involvement (under the auspices of the national CMAM working group). MAM guidelines are also in development, but issues around commodity supply costs at scale and competing agency mandates have hampered integration with SAM guidance and finalisation. A detailed scale-up plan for integrated SAM treatment is now in development for 16 priority provinces; supplies are one hundred per cent funded by the Department of Health’s 2016 Annual Investment Plan.

Background

The Philippines is a middle-income country that has enjoyed reasonable economic growth in recent years. Progressive Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth is projected for 2016, with a 6.3% increase from a 6.1% increase in 2014 (Asian Development Bank, 2015), positioning the Philippines among countries with the highest economic growth in Southeast Asia. However, compared to other countries in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, the country’s nutrition indicators are still lagging. While the 2015 Global Nutrition Report shows the Philippines to be “on course” towards achieving the stunting target, (although more recently released 2015 National Nutrition Survey data show an increase from 30% to 33.4% in 2015), the country is “off course” in progress towards the targets for wasting in children under five years old and anaemia among women of reproductive age by 2025.

The Philippines is a middle-income country that has enjoyed reasonable economic growth in recent years. Progressive Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth is projected for 2016, with a 6.3% increase from a 6.1% increase in 2014 (Asian Development Bank, 2015), positioning the Philippines among countries with the highest economic growth in Southeast Asia. However, compared to other countries in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, the country’s nutrition indicators are still lagging. While the 2015 Global Nutrition Report shows the Philippines to be “on course” towards achieving the stunting target, (although more recently released 2015 National Nutrition Survey data show an increase from 30% to 33.4% in 2015), the country is “off course” in progress towards the targets for wasting in children under five years old and anaemia among women of reproductive age by 2025.

The country showcases glaring, income-based inequities and its health systems are regularly challenged by natural disasters and armed conflict. Political factors, weak policies and decentralisation resulting in muddled accountabilities at local and national levels have resulted in low access to essential nutrition and health services in remote, poor and minority communities. Political patronage and the lack of “voice” of the poor mean that health and nutrition expenditures are often skewed in favour of the rich. Research from the World Bank finds that the Philippines is one of only 20 countries in the world (among 69 assessed) where government expenditure on health is “significantly pro-rich” (Wagstaff, Bilger, Buisman et al, 2014). Being affected by more than 20 typhoons each year, the environmental context of the Philippines makes disaster preparedness and resilience particularly critical. It is the third-most disaster-prone country in the world, with high vulnerability not only to typhoons but also to flash flooding, volcano eruptions and earthquakes.

High Burden of Wasting

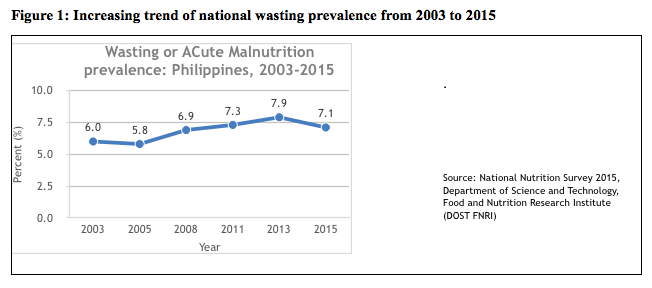

Despite substantial economic growth, the prevalence of wasting in the Philippines consistently increased from 2003-2013, with only a slight decrease in recent years. According to the 2015 National Nutrition Survey (Figure 1), wasting increased from 7.3% in 2011 to 7.9% in 2013, but decreased to 7.1% in 2015. This translates into an estimate of nearly 1.5 million wasted Filipino children under five years of age, around a third (estimated 500,000) of whom are severely wasted. The same survey noted regional variations for wasting in children 0 to 5 years of age, reflecting increasing inequities across the country. Wasting is a major concern in the Philippines, particularly as it is a highly disaster-prone country and since the risk of developing wasting increases during humanitarian emergencies.

Lack of policies, standard protocls, systems and capacity for the management of acute malnutrition

Since the 1970s, treating a child for malnutrition in the Philippines meant admission to a malnutrition ward (MalWard), a delegated area within a hospital that focused on fully accommodating the special needs of children with malnutrition. Over time, priorities of hospitals were shifted away from malnutrition, leading to the deterioration or subsequent phasing out of the MalWards. Furthermore, the treatment of malnutrition was largely hospital-based, with clinicians using outdated protocols. Over the years, local government units (LGUs; equivalent to districts) have been resorting to supplementary feeding initiatives at the school or community level to treat wasting in young or school-age children. These initiatives were, and still are, managed by school or health workers who are neither trained on adequate, evidence-based management of wasted children, nor equipped with the necessary tools to identify or report such cases. The management of severe acute malnutrition (SAM) remained a key emergency response intervention during the recurrent natural disasters and conflicts in the Philippines from 2008 to 2013, but could not be carried out at scale in the absence of a national protocol and guidance to inform a coherent, country-wide scale-up.

When super-typhoon Haiyan impacted the Philippines in November 2013, the SAM management programme, which was led by the Philippine National Nutrition Cluster, was effective in saving the lives of around 1,000 children with SAM as part of its strategic response plan, but again highlighted the lack of national policy, standard protocols, systems and capacity essential for the sustainability and scale-up of essential services for children with SAM. The experience from the Haiyan emergency response, coupled with the evidence-based advocacy efforts of the Nutrition Cluster and partners, also resulted in increased awareness and demand from LGUs on improving access and availability of essential services for children with SAM.

To address the high burden of SAM in the country, the Philippine Nutrition Cluster prioritised the urgent need to support the development of national protocols and policy on the management of SAM for children under five years of age. This was achieved through its community-based management of acute malnutrition (CMAM) working group led by the Department of Health (DOH). The broad objective of this prioritisation was to improve the access and availability of life-saving services for children with SAM through the institutionalisation of SAM management within the national and local health systems, in both emergency and non-emergency settings.

Development and endorsement of national protocols and policy for management of SAM in children under five years of age

In 2011, with the objective of institutionalising CMAM as part of health-systems strengthening, the Nutrition Cluster, supported by UNICEF, started the development of national guidelines for the management of SAM in the Philippines. A consultative workshop was organised where various stakeholders, including staff from the DOH and members of the CMAM task force of the Philippines, were engaged to adapt generic protocols into the Philippine Integrated Management of Acute Malnutrition (PIMAM) protocols. However, due to the unavailability of essential commodities (ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF), F-75 and F-100) in the country, procurement concerns by the DOH, and lack of a defined operational component in the PIMAM protocols, the guidelines could not be adopted by the DOH.

Despite the lack of endorsement as a national policy, the PIMAM guidelines were used by Nutrition Cluster partners and the Philippine Government as a reference to deliver emergency nutrition services during several high-impact humanitarian emergencies. Between 2011 and 2015, the Philippines was repeatedly affected by several disasters (including tropical storm Washi, typhoons Bopha and Haiyan, the Bohol earthquake and armed conflicts in Zamboanga City and central Mindanao), where the protocols were implemented to provide life-saving care to affected children. In addition to emergencies, the draft PIMAM protocol was also implemented in the urban development context of Davao City in 2014.

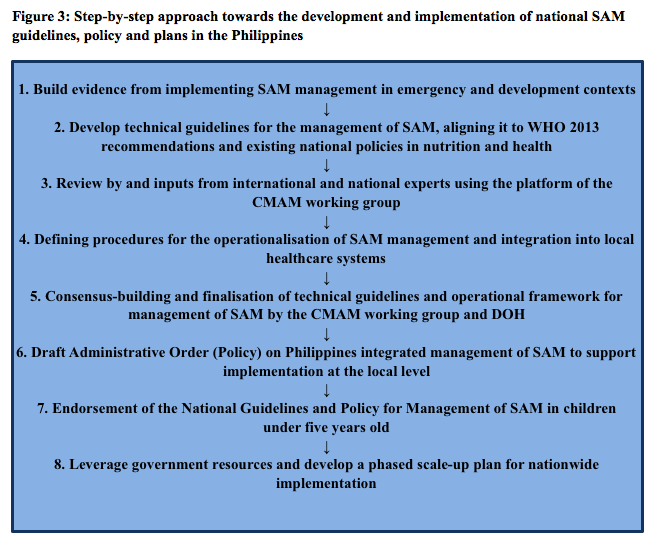

The experiences of implementing SAM management programmes over the last seven years in various settings in the country have resulted in building local capacity in the programme areas and have generated the evidence necessary at local level to support national advocacy. The number of trained healthcare staff at national, regional and district levels has increased. In 2014 alone, 1,766 healthcare personnel (doctors, nurses, midwives and community nutrition/health volunteers) were trained on SAM management protocols. The number of functional outpatient and inpatient therapeutic care centres increased from 62 health facilities in 2012 to 313 community health stations and hospitals in 2014 (see Figure 2). These facilities have been providing life-saving services to children under five years of age with SAM since then (UNICEF, 2014). Although these experiences were successful in providing life-saving care to children with SAM, largely in emergency-affected contexts, they highlighted the critical gaps in the lack of national policy, DOH-endorsed standard protocols, systems and capacity essential for the sustainability of the initiatives and the scale-up of services for children with SAM in every barangay (village).

In mid-2014, realising the urgent need to integrate the services for management of SAM into the regular health system and to address identified critical gaps, with UNICEF’s support the Nutrition Cluster reinitiated the process of updating the 2011 draft guidelines. Members of the DOH-led national CMAM working group (one of the four technical working groups under the National Nutrition Cluster) identified key gaps in facilitating the endorsement of the national guidelines and policy. These were: (1) Inclusion of the operational component into the national guidelines for integrating services for SAM into health systems; (2) A consultative and transparent guidelines development process involving national experts from various fields (practitioners, academicians, implementers, administrators and service providers); (3) Aligning the technical guidelines to the most recently updated World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations for the management of SAM in infants and children (WHO, 2013); (4) Passing the leadership for guidelines development on to DOH for increased ownership of the guidelines; and (5) Developing guidelines with a focus on implementation during both non-emergency and emergency settings.

While guidelines for the management of SAM were being developed, the Nutrition Cluster was also updating the guidelines for the management of moderate acute malnutrition (MAM) with technical support from the World Food Programme and Save the Children. The initial plan was to merge the two guidelines as one for endorsement by the DOH. However, the finalisation of the MAM guidelines and their integration into the SAM guidelines were hampered due to supplementary food supply cost at scale and competing agency mandates in developing the guidelines. There was a lack of consensus by the CMAM working group on the supplementary food to be used for the treatment and the high costs associated in using ready-to use supplementary food (RUSF) or a locally produced supplementary food for treating children with MAM at scale using national government resources. In light of the delays over finalisation of MAM guidelines, the cluster decided to move ahead with the endorsement of the guidelines and policy for SAM management. The MAM guidelines will now be integrated into the national guidelines on supplementary feeding being developed by the National Nutrition Council (NNC). However, both guidelines and policy on SAM management include and define the preventive linkages with MAM management in the community.

Under the leadership of the DOH, with technical support of UNICEF1 and in consultation with partners and experts using the platform of the national CMAM working group, national guidelines for the management of SAM were developed and submitted to the Philippine Government for endorsement. This consultative and participatory process, which lasted for about one and a half years, led to an improved understanding and ownership of the government on the criticality of the SAM management programme within the ongoing health-systems strengthening. This, coupled with having a defined operational component for implementing the technical protocols with details on supplies and programme costing integrated into the health systems, resulted in DOH endorsing the national guidelines and the policy. On 1 October 2015, the National Guidelines for the Management of SAM for children under 5 years were signed by the DOH Secretary and launched on 5 November 2015 in Manila. In December 2015, the DOH issued Administrative Order 2015-055, its highest policy instrument for the health and nutrition sectors, providing the policy and strategic framework to guide the adoption and implementation of the national guidelines at the local level. In parallel, DOH and UNICEF teams worked on developing a draft scale-up plan to implement the SAM management programmes in a phased approach. This process involved a series of technical discussions with DOH programme officers on essential supply requirements and product registration, caseload calculations, costing projections and identification of priority areas. A total of 16 priority provinces were identified2 for Phase 1 of SAM programme scale-up by the DOH starting in 2016.

These actions show the commitment of the Philippine Government to achieve kalusugang pangkalahatan (universal healthcare) by integrating the services for management of children with SAM into the routine healthcare system. In line with the country’s commitments to Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN), the Second International Conference on Nutrition, and the World Health Assembly Resolution on Maternal, Infant and Young Child Nutrition, the DOH has allotted US$3.3 million in its 2016 investment plans for the scale-up of SAM management services, targeting 34,000 children with SAM in 16 priority provinces. The costs in the investment plans are for procurement of SAM programme commodities (RUTF, F-100, F-75 and basic medicines), together with some training and programme costs per province. The gaps in training component of the scale-up in 2016 are being supported by UNICEF, using emergency and development programme funds. The DOH has plans to fund the other phases of the SAM management scale-up, expanding it to all the provinces in the country. Under the SUN commitment, efforts are also being made by nutrition partners to raise more funds for nutrition in the Philippines. Given its middle-income country status, however, partners – including the UN – are finding it very difficult to raise funds for nutrition. While the annual budget of the DOH has been increasing (tripling in the last four years), only a small share is earmarked for nutrition interventions. The focus for SUN partners is therefore on strengthening the investment case for nutrition, with continued advocacy on increased government investment for nutrition. This effort is linked to developing the SUN Common Results Framework, which is aligned to the new Philippine Plan of Action for Nutrition (2017-2022).

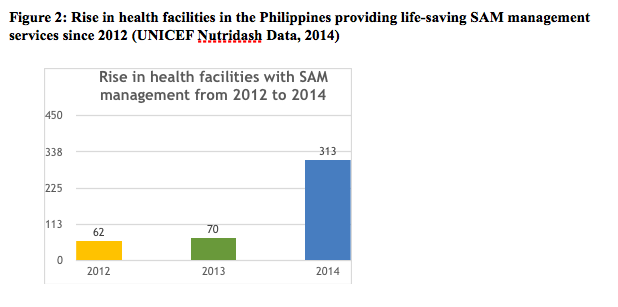

Figure 3 summarises the step-by-step approach for the development of the national guidelines, policy and plans in the Philippines. The evidence generated from both emergency and development SAM programming facilitated the development of draft guidelines aligned to global updates and national policies. Using the CMAM working group platform with technical inputs from international and national experts, technical guidelines and the operational framework were finalised. Using a consultative and participatory process involving national and local actors, defining procedures, tools and indicators, the necessary consensus was built. This led to the ownership and endorsement of the national guidelines, policy and plans. This has been a major achievement by the Philippine Government towards institutionalising SAM management services into the routine healthcare system. This achievement is also a milestone of Philippines’ commitment to SUN, as the members of the CMAM working group under the Nutrition Cluster are also the members of various networks under the SUN multi-partner platform. The Philippines has the advantage that the DOH’s NNC plays the dual role of Nutrition Cluster chair and the SUN Secretariat in the Philippines. This has led to greater involvement of the SUN stakeholders in ownership of the national guidelines.

Lessons learned from SAM national protocols and policy development in the Philippines

- Updating and developing national guidelines is a critical step towards building consensus among all actors in and outside the Government and in agreeing to collectively support SAM management programmes.

- The process of protocols development should be participatory and consultative (involving both national and sub-national actors) to ensure ownership of the programme and protocols.

- For the Government to endorse the SAM management protocols and plan scale-up, it is important to include both technical and operational components in the guidelines.

- International standards and protocols need to be subjected to consultation, adapted to country realities and contextualised in order to improve acceptance and ownership.

- The development of practical and user-friendly protocols is critical. Clarity for end users of the protocol should be ensured.

- Simplified tools and job aids are critical protocol components. Protocols should undergo consensus and testing at the sub-national and national levels.

- SAM management protocols should address all four components of CMAM and MAM protocols, which need to be integrated from the beginning of the protocols development process.

- Protocols need to be developed for both emergency and non-emergency contexts for both SAM and MAM.

- DOH chairing of the national CMAM working group and leading on the protocol development process improved ownership, which was critical for the validation and endorsement of the protocols, policy and budget.

After an intensive and consultative process, the National Guidelines for Management of SAM have been adopted by the Philippine Government as an evidence-based and equity-focused nutrition intervention for children under five years old. The DOH, UNICEF and the Nutrition Cluster are working towards countrywide scale-up of the National Guidelines for Management of SAM and are in the process of developing a detailed scale-up plan. Phase 1 of the scale-up plan is for implementation in 16 priority provinces, starting in 2016. Key components of the scale-up plan include: 1) Dissemination of national policy and protocols at the local level; 2) Capacity-building of trainers and implementers at the national and local levels; 3) Establishing procurement systems of essential SAM management commodities; 4) Establishing monitoring and reporting systems, including bottleneck analysis; 5) Advocacy and communication for effective community mobilisation and institutionalisation of SAM management services in pre-service and in-service curricula of service providers; and 6) Linking SAM management services with the Conditional Cash Transfer Programme and PhilHealth (national health insurance entity) out-patient and in-patient insurance packages.

For more information, contact: Aashima Garg, or agarg@unicef.org

References

1 Valid International provided international technical expertise in the development of the national guidelines.

2Priority provinces identified were based on DOH’s 43 priority provinces; those with high levels of wasting based on the National Nutrition Survey (2013); and those that are hazard-prone and have existing capacities for implementation of outpatient and inpatient therapeutic care services.

Asian Development Bank 2015. Asian Development Outlook 2015: Financing Asia’s Future Growth.

UNICEF 2014. Nutridash 2013: Global Report on the Pilot Year. New York: UNICEF, 2014.

Wagstaff A, Bilger B, Buisman L, Bredenkamp C, 2014. Who Benefits from Government Health Spending and Why? A Global Assessment. Policy Research Working Paper No. 7044. World Bank Group, Washington DC. 2014.

WHO 2013. Updates on the management of SAM in infants and children guideline. World Health Organization 2103.