Social Return on Investment (SROI) assessment of a Baby-Friendly Community Initiative in urban poor settings, Nairobi, Kenya

By Sophie Goudet, Caroline W. Wainaina, Teresia N. Macharia, Milka N. Wanjohi, Frederick M. Wekesah, Peter Muriuki, Betty Samburu, Paula L. Griffiths and Elizabeth W. Kimani-Murage

This research was supported by the research consortium Transform Nutrition, funded by the UK Department for International Development, but the views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the UK Government’s official policies. The original intervention study was funded by the Wellcome Trust, UK. We are grateful to the Unit of Nutrition and Dietetics and the Unit of Community Health Services at the Ministry of Health, Kenya; the sub-County Health Management Teams in Makadara and Kasarani; and the Nairobi County Council. The authors would also like to thank UNICEF, Concern Worldwide, the Urban Nutrition Working Group and the Nutrition Information Working Group convened by the Unit of Nutrition and Dietetics, among other agencies, NGOs and organised groups for their guidance and support in the design and implementation of the intervention. The team thank Tim Goodspeed of Social Value UK for mentorship on SROI assessment. The team is also indebted to the study community, the community health volunteers involved and the data collection and management teams.

This research was supported by the research consortium Transform Nutrition, funded by the UK Department for International Development, but the views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the UK Government’s official policies. The original intervention study was funded by the Wellcome Trust, UK. We are grateful to the Unit of Nutrition and Dietetics and the Unit of Community Health Services at the Ministry of Health, Kenya; the sub-County Health Management Teams in Makadara and Kasarani; and the Nairobi County Council. The authors would also like to thank UNICEF, Concern Worldwide, the Urban Nutrition Working Group and the Nutrition Information Working Group convened by the Unit of Nutrition and Dietetics, among other agencies, NGOs and organised groups for their guidance and support in the design and implementation of the intervention. The team thank Tim Goodspeed of Social Value UK for mentorship on SROI assessment. The team is also indebted to the study community, the community health volunteers involved and the data collection and management teams.

Location: Kenya

What we know: The social impact of nutrition interventions is not well evidenced.

What this article adds: The social impact of the Maternal, Infant and Young Child Nutrition (MIYCN) project in Kenya was investigated using a Social Return on Investment (SROI) analysis method. Data collection used a mixed-methods approach; 281 stakeholders participated. Value games were used to place value on outcomes which did not have a market value. Chain of events described how one outcome led to another. The MIYCN intervention showed overall an important positive impact. The results confirmed the expected results (e.g. having healthier children, mother being healthier), identified other positive outcomes that were not expected (e.g. mothers received more support from fathers) and identified some negative outcomes (e.g. stress transitioning from exclusive breastfeeding). The outcomes with most social value to mothers and children stakeholders were ‘healthier mother’ and ‘less worried mother due to better health’. The team will investigate the design of a less time and budget-intensive SROI for nutrition interventions.

This article presents the social impact of the Maternal, Infant and Young Child Nutrition (MIYCN) project; a pilot project from the African Population and Health Research Centre (APHRC) that aimed to improve the health and nutrition of mothers and children and inform implementation of the Government’s Baby-Friendly Community Initiative (BFCI). The findings presented here used a Social Return on Investment (SROI) analysis, an accepted method of measuring the social impact of programmes in a participatory way that uses financial proxies to measure the value of changes that stakeholders experience (positively and negatively). As SROI is a relatively new evaluation method in nutrition interventions, this paper largely focuses on the tools and methodology used.

Background

APHRC, in collaboration with the Unit of Nutrition and Dietetics and the Unit of Community Health Services at the Ministry of Health in Kenya, implemented a research project consisting of home-based nutritional counselling of mothers by Community Health Volunteers (CHVs) known as the Maternal, Infant and Young Child Nutrition (MIYCN) project (http://bit.ly/1HARcJB). The MIYCN intervention was a randomised controlled trial, testing the Baby-Friendly Community Initiative (BFCI) in urban slums in Kenya (Kimani-Murage et al, 2013). A total of 1,100 pregnant women and their respective children were recruited into the study and followed up. The mother-child pairs were followed up until the child was up to one year old. The mothers received regular, personalised, home-based counselling by trained CHVs on MIYCN. Regular assessment of MIYCN knowledge, attitudes and practices was conducted, together with assessments of nutritional status of the mother-child pairs and diarrhea morbidity among the children. The project was conducted in Korogocho and Viwandani slums of Nairobi from 2012 to 2015 and was funded by the Wellcome Trust.

Methodology

Stakeholders form the basis of an SROI as organisations or people who were impacted directly or indirectly by the project; they report on the outcomes and value them. Here, the included stakeholders were the mothers recruited in the study, their children, siblings of the children, fathers of the children, grandmothers, healthcare providers, the data collection team and daycare centres operational in the intervention area.

Data collection used a mixed-methods approach (focus group discussions (FGDs), key informant interviews (KIIs), in-depth interviews (IDIs), quantitative stakeholder surveys, and revealed preference using value games). The qualitative approach explored the impact of the intervention per stakeholder using data from 19 FGDs, 27 KIIs and 20 IDIs with a total of 161 participants. The quantitative stakeholder survey assessed the level of impact (frequency of people reporting an outcome), explored costs, duration and comparison with outcome if the project had not taken place. Data were collected on 281 participants (separate questionnaire for mothers, CHVs, grandmothers, daycare centres, business community, healthcare providers and data collection team). Value games were used to place value on outcomes which did not have a market value (e.g. confidence). These were conducted using additional 16 FGDs (mothers, fathers, grandmothers, CHVs, and data collection team) and six KIIs (daycare centres and therapeutic feeding centres). Findings were crosschecked and triangulated using other sources of data (randomised controlled trial and cost-effectiveness analysis using qualitative data).

The chain of events described how one outcome led to another to end up with the identified outcome. For example, the outcome ‘mothers were less worried’ was at the end of the following chain of events: “The counselling on household hygiene to mothers resulted in improved knowledge about hygiene practices and better household hygiene practices. Babies were reported to have less diarrhoea and increased weight gain. This resulted in fewer hospital visits and reduced expenditure on healthcare. Mothers were less worried”. These chains of events were detailed for each outcome using participant citation, which provided deeper understanding of how the intervention impacted people’s lives. Financial proxies were identified to value the impact of the outcome with or without market value. For outcomes such as ‘increased cost of healthcare and nutritious food’, we asked stakeholders in the quantitative questionnaire and used the average cost. For outcomes such as ‘mothers were less worried’ or ‘data collection team members were more confident’, we used willingness to pay via value-games exercises (see Box 1 for an example of a value game with grandmothers; see also following link to a value-game video, click here.

Box 1: Valuing social outcomes: value game example with grandmothers

The value game was used to determine the monetary value of outcomes without market values. In the case presented below, the grandmothers were willing to pay USD6,000 to be happy and USD9,000 to have a lesser burden of care.

Steps in SROI value game

- The grandmothers individually list at least three to four material items they can buy/have bought for them that can last at least a year.

- The list is compiled and the grandmothers list the items in order of priority from what would make them happiest to least happy.

- The grandmothers then place the outcome of interest in the ranked outcomes, again in order of priority.

- The material items are then ranked according to their worth in monetary value for one year, from the most to the least expensive.

- The outcomes of interest are then placed back in their original positions and valued.

- Finally, the grandmothers were asked if they agreed with the value of the outcome of interest.

We estimated a number of stakeholders who reported the outcome based on frequency in stakeholder questionnaire with inference to the general population. The duration of the outcome was estimated based on stakeholders’ responses in the questionnaire. In the analysis, skills and heath-related outcomes that can have ‘life-lasting’ impact were limited to five years, as they were complicated to evaluate beyond this period. Assumptions were made to take into account whether other organisations or people contributed to the impact (attribution); if the intervention displaced activities (displacement); what would have happened anyway (deadweight); and what the decline over time would be (drop off). Assumptions were also made to recognise how future financial values are worth now using discount rate.

Results

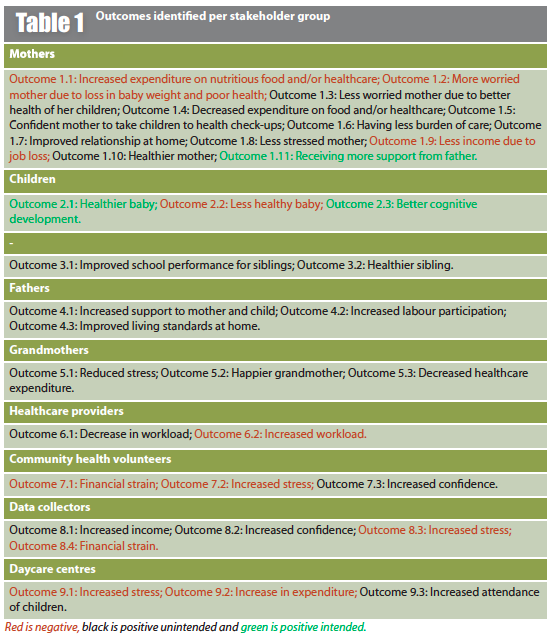

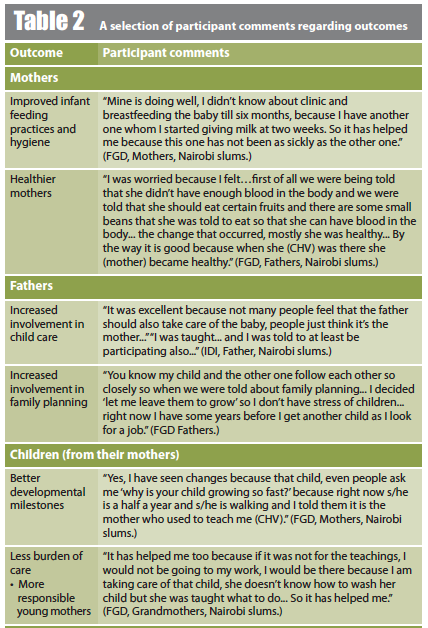

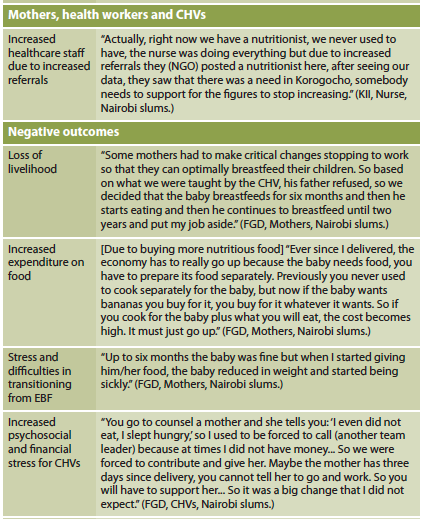

In the SROI process, outcomes were identified as perceived by the stakeholders and their values using financial proxies. The results confirmed the expected results (e.g. having healthier children, mother being healthier), identified other outcomes that were not expected (e.g. mothers received more support from fathers) and some outcomes identified were negative (e.g. increased level of worry for mothers due to challenges in introducing complementary feeding after exclusive breastfeeding for six months). In total, 34 outcomes were identified, with 11 negative ones and 20 positive but not expected (see Tables 1 and 2).

The analysis estimated that, after accounting for discounting factors, the input ($USD419,716) generated $USD8 million of social value at the end of the project (for more on the findings see SROI Short Report (aphrc.org/publications/social-return-investment-assessment-baby-friendly-community-intervention-urban-poor-settings/) and the BFCI Policy Brief (aphrc.org/publications/measuring-value-baby-friendly-community-intervention-nairobis-slums/).

The net present value created by the project was estimated at $USD29.5 million. The SROI analysis showed that the MIYCN programme was assessed highly effective and created social value: US$1 invested in the project was estimated to bring US$71 of social value for the stakeholders.

Limitations

The limitations were related to the complexity of assessing future health benefits and the challenges in valuing non-market-valued outcomes. We decided therefore not to value future health benefits and to limit the duration of impact to five years. We feel that this may underestimate future health benefits, but without data on how to evaluate these we preferred not to include them. We used willingness to pay via value games to monetise outcomes without market value such as confidence, burden of care, worry, happiness, etc. While value-game exercises were done to minimise subjectivity and to reach a consensus per stakeholder group, sensitivity analysis showed that the SROI ratio was mostly sensitive to these.

Discussion and conclusion

The MIYCN intervention showed overall an important positive impact. The intervention resulted in better mother and child health and increased confidence of mothers to exclusively breastfeed and better nutritional outcomes, among other things. Unexpected benefits were identified that could only be accounted for and quantified using the SROI approach. The impact was less important for grandmothers, fathers and CHVs. Nevertheless, these stakeholders also reported positive outcomes such as increased happiness and improved living standards at home. Key negative outcomes were also identified; for example, women foregoing work in order to breastfeed their children optimally, since their workplaces were not supportive. Overall, the intervention had a negative impact on daycare centres and healthcare providers, putting too much pressure on them without providing extra support. Daycare managers reported having to invest more but with the same income, as mothers were not willing to pay for improvements in the daycare centres. Community health volunteers also underwent psychosocial and financial stress emanating from the level of poverty in the communities in which they were working. Future interventions should consider such potential negative outcomes and find measures to mitigate them, which may include finding social protection measures for vulnerable populations.

A comparison of the MIYCN SROI ratios against other SROI studies showed the ratio obtained was the highest so far, but this is also the only study that assessed nutrition-promotion (Banke et al, 2015). The outcomes that generated the most social value to mothers and children stakeholders were ‘healthier mother’ and ‘less worried mother due to better health’. The negative outcomes that will need to be tackled in future programming are: ‘less healthy baby due to difficulty in introducing complementary feeding after six months’; ‘[stress transitioning from] exclusive breastfeeding’ for children and ‘increased workload for healthcare workers due to mothers seeking child check-ups’. These findings led to a policy brief and recommendations (see Box 2).

SROI, as an evaluation tool, is very powerful but can be costlier and more time-consuming than other evaluation methods, such as cost-effectiveness analysis. The team will investigate the design of a lighter SROI for nutrition interventions that can respect the SROI principles while meeting time and budget constraints.

Box 2: Policy recommendations

1. National and county governments and donors

- Fund BFCI as a priority health-promotion tool. BFCI has many far-reaching positive impacts on the health and wellbeing of both family and community members, including, mothers, fathers, children and grandmothers.

- Support the community health strategy by providing incentives for community health volunteers and adequately training CHVs on handling psychosocial issues.

- Empower the community economically through social protection measures such as job-creation and support of mothers who wish to successfully combine work with breastfeeding.

- Include fathers in BFCI interventions as they are a key determinant to its success.

2. Researchers, NGOs and donors

- Adopt SROI approach in evaluation of interventions in order to manage unexpected outcomes and value social outcomes.

- Build the capacity of program implementers to include SROI in their evaluations.

For policy brief and recommendations, click here

For more information, contact: Sophie Goudet or Elizabeth Kimani-Murage

More details on the findings and plans are available at the socialvalueofnutrition website.

References

Banke-Thomas AO, Madaj B, Charles A, & van den Broek N, 2015. Social Return on Investment (SROI) methodology to account for value for money of public health interventions: a systematic review. BMC Public Health, 15, 582. doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1935-7

Kimani-Murage EW, Kyobutungi C, Ezeh AC, Wekesah F, Wanjohi M, Muriuki P, Musoke RN, Norris SA, Griffiths P, & Madise NJ, 2013. Effectiveness of personalised, home-based nutritional counselling on infant feeding practices, morbidity and nutritional outcomes among infants in Nairobi slums: study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. Trials 14.1: 445. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-14-445.