Using care groups in emergencies in South Sudan

By Peter Ndungu and Julie Tanaka

Peter Ndungu is a Nutrition Programme Manager with Samaritan’s Purse South Sudan. He manages the Blanket and Targeted Supplementary Feeding Programmes and the Care Groups IYCF project. He previously worked with MSF in nutrition programmes in South Sudan and Nigeria. Peter is a trained clinician and is currently completing his Masters in Public Health.

Peter Ndungu is a Nutrition Programme Manager with Samaritan’s Purse South Sudan. He manages the Blanket and Targeted Supplementary Feeding Programmes and the Care Groups IYCF project. He previously worked with MSF in nutrition programmes in South Sudan and Nigeria. Peter is a trained clinician and is currently completing his Masters in Public Health.

Julie Tanaka is the Senior International Nutrition Advisor for Samaritan’s Purse. She helps field offices around the world with programme design, proposal review, implementation, nutrition surveys, trainings, monitoring and evaluation, and emergency relief.

The authors would like to thank the Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance for funding the project and to acknowledge Kimberly Ostrum and Gracie Fairfax for their help in the development of this article and the Samaritan’s Purse South Sudan team for their assistance in the implementation of this project.

Location: South Sudan

What we know: The Care Groups Model is a common approach to achieve social and behaviour change.

What this article adds: A Care Groups project targeting infant and young child feeding (IYCF) behaviour change was initiated by Samaritan’s Purse in South Sudan in 2015. Escalation in violence soon afterwards led to adaptation of the care groups model to the emergency context (characterised by a transient population and short-term funding). The core delivery structure of Programme Coordinator, Supervisor, Promoters, Lead Mothers and Neighbourhood Women was retained. The main adaptation was to have open groups, allowing mothers to join and leave groups at will, enabling continued access for those displaced. Project staff identified beneficiaries at household level (looking for saturation registration of target group). Informal communication networks facilitated easy flexibility and adaptation. Smaller groups worked best. An endline Knowledge, Attitudes and Practice (KAP) survey found improvements in IYCF practices; endline SMART found a deterioration in nutritional status of children, indicative of prevalent food insecurity.

Background

On December 15, 2013, violence erupted in Juba, South Sudan, following fighting between government and opposition forces. The violence rapidly spread to other parts of the country, causing displacement of an estimated 1.5 million people. Ongoing military campaigns have been concentrated in three key strongholds across the county: Jonglei, Upper Nile and Unity State. Samaritan’s Purse (SP) is currently working in various counties within Unity State and Upper Nile State, serving at-risk populations with WASH (water, sanitation and hygiene), food security, livelihoods and nutrition interventions. The nutrition interventions include a stabilisation centre (SC), outpatient therapeutic programmes (OTP), targeted and blanket supplementary feeding programmes, general food distributions, mother-to-mother support groups and care groups.

The county in Unity State where Samaritan’s Purse implemented a Care Groups project is one of the most affected counties in the ongoing South Sudan conflict. Fighting has continued to have devastating effects on the population, leading to loss of life, destruction of property and infrastructure, and massive population movement. Most of the men are engaged in military activities, with women acting as head of the household. This has increased women’s workload and caloric expenditure, which in turn has increased their risk of malnutrition. Moreover, now that women are carrying out many roles, the amount of time they are able to spend feeding and caring for their children has decreased, which increases children’s risk of malnutrition. Agriculture is the county’s primary economic activity. The people are nomadic agro-pastoralists who engage in both agriculture and the rearing of livestock, especially cattle. Fishing is also a major part of people’s livelihoods. The population is very transient. The men often move around to look for pastures for their livestock and for military activities. The women frequently move location to look for food or to access healthcare.

Project context

An Initial Rapid Needs Assessment (IRNA), conducted by Samaritan’s Purse in March 2014, indicated that many of the internally displaced believed that because mothers did not have enough food, they could not produce enough breastmilk. This led to children as young as four months old being given undiluted animal milk to supplement breastmilk. Because of the lack of staple foods, mothers were unable to introduce adequate complementary feeding. Consequently, some children over six months old were relying solely on breastmilk for nutrition. Children aged 6-23 months were not meeting minimum dietary diversity requirements or minimum meal frequency requirements. This information, combined with the lack of previous infant and young child feeding (IYCF) interventions, indicated the need to promote IYCF practices in the target county.

On December 15, 2015, Samaritan’s Purse started a Care Groups project in five payams1 in Unity State. A few months before implementation began, fighting in the county escalated because control of the town switched from opposition to government forces. The county was greatly affected by the conflict because of the ethnic profile and militarisation of residents. After many were killed, people from the area fled into the swamps. Some lived there for weeks, others for months, drinking dirty water and eating wild foods such as lily pods. Samaritan’s Purse decided to proceed with the planned Care Groups project, even though the situation had changed from a protracted emergency to a more acute emergency context.

Care Groups approach

The Care Groups project proposed to reduce nutrition-related morbidity and mortality through the promotion of IYCF practices and behaviour-change services to women of reproductive age (WRA) aged between 15 and 49 years. Optimal IYCF practices were encouraged and women were empowered to overcome key barriers by developing creative solutions in the circumstances. Mother-in-laws and grandmothers, who play an influential role in child-rearing, were incorporated into the project during home visits.

The Care Groups Model was selected to deliver the proposed IYCF activities, given the evidence base behind using Care Groups for social and behaviour change. Many tools and resources compiled by practitioners of the model, and its capability to reach 100% of target beneficiaries, have made it one of the best-practice methodologies in promoting social and behaviour change for health and nutrition projects. Given the escalation in conflict with a now more transient population, and since only one-year funding was available (U.S. Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA)), the Care Groups Model was adapted to fit the acute emergency context more practically.

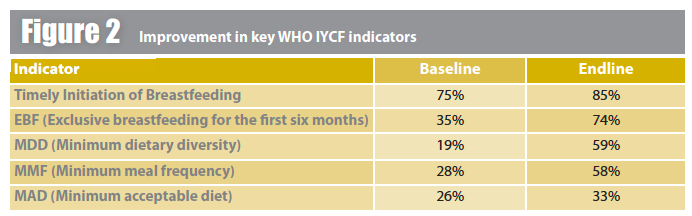

A Knowledge, Attitudes and Practice (KAP) survey was conducted at the outset to provide a baseline of IYCF practices and was used to inform the development and focus of the training manual. A two-stage cluster sampling methodology was used for a total sample size of 1,132 caregivers of children aged 0-23 months. In the first stage, clusters were selected using probability proportional to size (PPS). The Expanded Programme on Immunisation (EPI) method was used in the second stage for household selection. Results of the KAP survey revealed that 19% of children sampled met minimum dietary diversity requirements, 28% met minimum meal frequency standards, and only 26% had a minimum acceptable diet. Of the infants included in the survey, 35% were found to be exclusively breastfed, with a majority receiving breastmilk along with other liquids, including water and yogurt. Focus group discussions revealed local myths about babies needing oil and water for digestion before six months of age, gaps in knowledge around a woman’s breastmilk supply, cultural beliefs around what constituted proper ‘children’s food’, and issues with women’s time and workload that made breastfeeding and responsive feeding difficult.

A SMART survey was also conducted to supplement the KAP baseline survey. A sample size of 430 was used for children aged 6-59 months. The global acute malnutrition (GAM) prevalence was 16.1% [(12.1- 21.0, 95% C.I.] and the severe acute malnutrition (SAM) prevalence was 2.4% [1.3-4.5, 95% C.I.]. The fact that the GAM prevalence was above the WHO emergency threshold highlighted the acute needs in the area. Stunting prevalence was 13% [9.3-17.4, 95% C.I.] The survey findings indicated poor health-seeking behaviours by the caregivers, with only 39.3% seeking assistance. This is likely due, in part, to the fact that only one primary healthcare unit was in operation in the county and healthcare access was particularly difficult for more remote villages. The Crude Mortality Rate (CMR) was 2.78 deaths per 10,000 per day [2.22-3.47, 95% C.I.], while the U5 Mortality Rate (U5MR) was 0.71 deaths per 10,000 per day [0.27-1.85 95% C.I. The CMR mortality rate was above the WHO emergency threshold.

Care Group structure

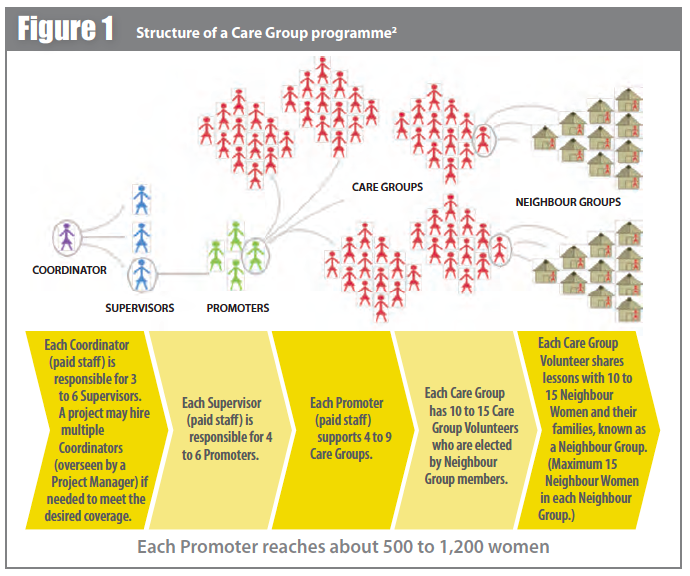

In the Care Group model, paid staff (Promoters), are trained by the Programme Supervisors and the Programme Coordinator (see Figure 1). The Promoters would, in turn, train Leader Mothers (LMs), who are formed into Care Groups. These LMs then train Neighbour Women (NW), either in Neighbourhood Groups or in one-on-one, bi-weekly sessions, with messages they are taught by the Promoters. This cascade model relies on the strength of LM volunteerism and usually achieves greater coverage of the target population and greater behaviour-change results than traditional mothers’ club methods. Because of its intense monitoring and evaluation, preparation work and comprehensive coverage, this approach is not usually employed in an emergency context.

In this Samaritan’s Purse Care Groups project, the paid Promoters were trained on the Care Group model protocols, IYCF behaviour change and participatory training methods. The six IYCF topics that were covered were: timely initiation of breastfeeding (colostrum feeding); exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months; complementary feeding after six months with soft foods and gradual increasing of amounts and density with age; continued breastfeeding up to two years; adequate feeding with breastfeeding/meal frequency three to four times a day; and balanced diet for children (healthy diet, fewer infections).

Due to the 12-month project implementation timeline, the programme found that the most expedient way to carry out the Care Groups census, used to identify beneficiaries and place them in groups, was to conduct house-to-house visits. A ‘Household Level Selection’ approach was used in which Promoters entered villages to systematically count 11 adjoining households (HHs). Women of reproductive age identified in each of the 11 adjoining HHs were registered for participation in the Care Groups project. Promoters covered every geographical area in the villages to ensure that all the women in the target group were accounted for. Among these HHs, the women would gather among themselves to appoint their own LM. They typically selected women who had confidence, commanded respect and trust, and were good public speakers. A total of 320 LMs were selected to form 32 Care Groups. Each Promoter was allocated eight CGs (80 LMs), in the payams they resided in. This ensured that Promoters did not walk for long distances to train, monitor and offer supportive supervision to the LMs. Each LM would reach her 10 NW through Neighbourhood Group meetings.

In traditional Care Groups projects, Neighbourhood Groups usually have a set number of women who do not change. For this emergency context, these groups were left open to accommodate women who moved; this was the most significant adaptation made to the Care Groups model for the emergency context. Throughout the one-year project period, the women remained transient, due to the slow trickle of displaced returnees and subsequent flooding in the area (requiring Promoters to use canoes to reach LMs). This meant that some LMs and NW were displaced from their original groups. To ensure that the women continued to receive behaviour-change messages, the LMs would trace the movement of the displaced women and connect them to Neighbourhood Groups in the locality where they moved, with assistance from the Promoters.

In addition to learning helpful health and nutrition information, displaced women were able to find a support structure in their Neighbourhood Groups that helped them in their transition. Displaced LMs were allocated NW for new groups if existing groups reached capacity. The tracing of population movement relied heavily on informal information channels, with Promoters and LMs sharing information via telephone and the grapevine of women who left and new women who arrived. These informal conversations allowed everyone to triangulate information and ensure everyone was accounted for.

Results

Even though the IYCF project in Unity State was only one year as opposed to the typical three-to-five year lifespan of a Care Groups project, it achieved significant results. The endline KAP survey was conducted with a sample size of 470 children aged 0-23 months using a two-stage cluster sampling methodology. The first stage used PPS to randomly select the clusters; the second stage used simple random sampling to select households. The results showed the improvement of key WHO IYCF indicators.

The endline SMART survey sampled 432 children aged 6-59 months and found a GAM prevalence of 19.6% [16.1-23.6, 95% C.I.]; a SAM prevalence of 3.6% [2.4-5.5, 95% C.I.]; and a stunting prevalence of 13.6% [10.7-17.2, 95% C.I.], indicating a deterioration and highlighting the need for greater coverage of acute malnutrition treatment services. Although the security situation stabilised during the year, a disrupted planting season and problems with flooding continued to plague the county, perpetuating a tenuous food security situation. It is likely that IYCF improvements are attributable to the Care Groups intervention and not due to a significantly improved external environment or other interventions that were started in the previous year.

In total, the Care Groups component within this larger, multi-sector project had a budget of US $345,402. The project:

- Trained 320 LMs on six IYCF topics, which they passed on to 320 neighbourhood groups, reaching 3,832 NW.

- Conducted two cooking demonstrations for 320 LMs; topics covered included hygienic handling, preparation and benefits of foods for nutrition.

- To ensure correct messages were passed on to the beneficiaries, IYCF promoters carried out 400 supervisory contacts with LMs during the trainings conducted in the community.

Lessons learned

In an emergency context, the census must be conducted in the most expedient way possible, given the limitations on time and length of funding. Using ‘Household Level Selection’ of beneficiaries allowed project staff to identify beneficiaries and place them in groups, and still allowed for 100% coverage of the target group and a group-nominated LM. This method worked well with transient populations in an emergency context, when it was not possible to get accurate and up-to-date lists of beneficiaries from community leaders.

Because of the saturation approach of the Care Groups model, all the women in the target age range (15 to 49 years of age) or target status (e.g. pregnant women) within a geographical area are registered to participate in the project. This methodology works well in areas where there may be tension among different socioeconomic, ethnic or livelihood groups, since it prevents workers from subjectively excluding some of the more vulnerable women from the project.

Allowing for shifting Neighbourhood Group membership enabled the project to adapt to population movement caused by insecurity and flooding. Frequent meetings and communication between project staff and beneficiaries allowed for the informal communication networks that facilitated easy flexibility and adaptation of the Care Groups when the displacement occurred and there was an influx of IDPs. This is why it was easy to connect NW to new groups.

In transient communities and those with frequent conflict, it is good to assign fewer women of whom the LMs are in charge. Neighbourhood Groups typically have between 10-15 NW, but it is best to limit the numbers of NW to around 10. This will allow the groups to accommodate more people if there is displacement, especially if there are expected seasonal displacements that happen on an annual basis. To prevent disruptions in the group leadership structure, LMs who relocate should appoint a replacement LM to lead the Neighbourhood Group.

For more information, contact: Julie Tanaka, jtanaka@samaritan.org

1 The second-lowest administrative division, below counties, in South Sudan, with a minimum population of 25,000.

2 The Technical and Operational Performance Support Program (TOPS) 2016. Care Groups: A Reference Guide for Practitioners. Washington, DC: The Technical and Operational Performance Support Program.

References

UNOCHA, 2015. UNOCHA Situation Report No.70 (as of 15 January 2015). reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/South_Sudan_SitRep_70_15Jan2015.pdf