Can low-literate community health workers treat severe acute malnutrition? A study of simplified algorithm and tools in South Sudan

Summary of research1

By Naoko Kozuki, Casie Tesfai, Annie Zhou and Elburg van Boetzelaer

The authors would like to acknowledge financial support from the Eleanor Crook Foundation.

Introduction

Low access to and coverage of acute malnutrition treatment are persistent challenges due primarily to distance from health services, high opportunity costs to caregivers, insecurity and lack of awareness of the signs and symptoms of malnutrition (Bliss, Njenga, Stoltzfus & Pelletier, 2016; Puett & Guerrero, 2015; Rogers, Myatt, Woodhead, Guerrero & Alvarez, 2015). Community-based delivery has been shown to increase the timely and effective treatment of childhood illnesses in low-resource contexts, such as through the integrated community case management (iCCM) of childhood illness strategy. ICCM equips community health workers (CHW) with training, simplified diagnostics, supervision and an uninterrupted supply of drugs to provide timely treatment for uncomplicated pneumonia, diarrhoea and malaria in the community. Community-based delivery models have also been tested to treat uncomplicated severe acute malnutrition (SAM). Recent studies from Pakistan, Malawi and Mali have shown positive outcomes in SAM treatment delivered by CHWs when compared to standard care at health facilities (Linneman et al, 2007; Puett, Coates, Alderman & Sadler, 2013). However, existing evidence is for literate CHW cadres only.

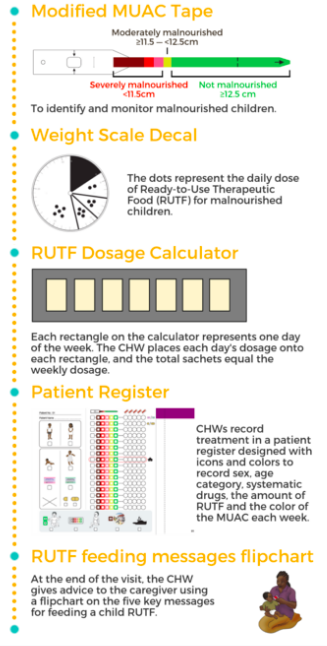

Recognising the burden of malnutrition to be higher in areas with lower education, income and healthcare access, the International Rescue Committee (IRC) developed tools and a protocol adapted for low-literate CHWs to treat uncomplicated SAM cases in their communities. A detailed description of the design process is available in Field Exchange Issue 52 (Tesfai, Marron, Kim & Makura, 2016). The five resulting tools were: 1) a patient register, 2) modified mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) tape, 3) weight scale decal to identify the daily dosage of ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF), 4) weekly RUTF dosage calculator, and 5) pictorial counselling cards (Figure 1). Following this, the IRC conducted a feasibility study to assess the ability of low-literate community-based distributors (CBD, the CHW cadre in South Sudan) to adhere to the treatment protocol using these tools. The treatment protocol followed South Sudan national guidelines for treatment of uncomplicated SAM, but MUAC was the only anthropometric tool used for admission, monitoring and discharge, and children were treated until fully recovered. Children were provided RUTF based on weight according to South Sudan national guidelines, but with half sachets rounded up. Treatment outcomes of children included in this study will be available in a future publication.

Figure 1: Simplified tools developed by IRC

Methods

A mixed-methods feasibility study was conducted to assess adherence of low-literate CBDs to a simplified SAM treatment protocol, the outcomes of children treated in the community by these CBDs, and the community acceptability of CBDs providing SAM treatment. Sixty CBDs in Aweil South County, Northern Bahr el Ghazal, South Sudan were randomly selected to receive training on the simplified protocol and tools, 57 of whom completed the training. Those who met a predetermined performance standard on a post-training assessment (n=44) were deployed to treat uncomplicated SAM in their communities. The checklist used to assess the performance is available in Annex 3 of the full report. Between May and September 2017, 320 SAM children were passively identified and enrolled, asked to return for weekly treatment, and followed until they reached a discharge outcome, with children treated to full recovery (two consecutive weeks with MUAC ≥12.5cm); 308 children had eligible results. CBD performance assessments were conducted during bi-weekly supervisory visits by research staff.

Results

In a performance assessment immediately after training, 91% of the CBDs passed the predetermined 80% performance score cut-off and 49% of the CBDs had perfect scores. Research officers conducted 141 case management observations during the study period, resulting in a mean score of 89.9% (95% CI: 86.4-96.0%). For each performance assessment completed, the final performance score of the CBD rose by 2.0% (95% CI: 0.3-3.7%). Treatment delivered by CBDs met SPHERE performance indicators, even when looking at treatment outcomes to full recovery. In total 75% of children were discharged as fully recovered, 15% defaulted from treatment, 9% were discharged as non-respondent, and no child was reported to have died under treatment. The median time of treatment to full recovery was eight weeks. All CBDs reported feeling proud of treating children for SAM and some gained respect in the community for this new responsibility. Overall, caregivers trusted CBDs to treat their children, but some caregivers and community leaders also expressed reservations that CBDs were keeping the RUTF for themselves or providing treatment to select children only.

Discussion

The high adherence by CBDs to a simplified treatment protocol in this study and overall local acceptability of this service show promise for deploying CBDs to improve access of acute malnutrition treatment, regardless of their literacy levels, in remote communities. The upfront investment to design tools and protocol suited to the skill set of CHWs in difficult contexts is invaluable in setting frontline health workers up for success and assuring programme effectiveness. In the hard-to-reach areas of fragile contexts with limited healthcare access, there is particular potential for the integration of nutrition treatment into the community-based service delivery model of iCCM to better stem the infection-malnutrition cycle and more effectively reduce the incidence of both.

A challenge experienced in developing a low-literacy protocol was how to monitor whether cases are stationary, regressing or progressing slowly in treatment. To address this, smaller MUAC colour zones were created and a safeguard for referral after four consecutive weeks in one colour zone was put in place. Based on the larger-than-normal proportion of referrals from this study (37%), further exploration is needed to adjust this safeguard.

Conclusion

Proper adaptations of tools and protocols can empower community health worker cadres with no formal education to provide critical lifesaving health services successfully. These results, combined with high recovery rates of the enrolled children, show great potential to increase effective coverage of acute malnutrition treatment in fragile contexts. The IRC is currently leading a consortium of four other non-governmental organisations (Action Against Hunger, Concern Worldwide, Malaria Consortium and Save the Children) to pilot versions of these tools adapted for other contexts to create a greater body of evidence behind CHW-delivery of acute malnutrition treatment.

For more information, please contact Casie Tesfai.

Endnote

1Link to full report here (treatment protocol available on pages 78-80) and Van Boetzelaer E, Zhour A, Tesfai C, Kozuki N. Performance of low- literate community health workers treating severe acute malnutrition in South Sudan. Matern Child Nutr. Pending publication in early 2019. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/17408709.

References

Bliss JR, Njenga M, Stoltzfus RJ & Pelletier DL. (2016). Stigma as a barrier to treatment for child acute malnutrition in Marsabit County, Kenya. Matern Child Nutr, 12(1), 125-138. doi:10.1111/mcn.12198

Linneman Z, Matilsky D, Ndekha M, Manary MJ, Maleta K & Manary MJ. (2007). A large-scale operational study of home-based therapy with ready-to-use therapeutic food in childhood malnutrition in Malawi. Matern Child Nutr, 3(3), 206-215. doi:10.1111/j.1740-8709.2007.00095.x

Puett C, Coates J, Alderman H and Sadler K. (2013). Quality of care for severe acute malnutrition delivered by community health workers in southern Bangladesh. Matern Child Nutr, 9(1), 130-142. doi:10.1111/j.1740-8709.2012.00409.x

Puett C & Guerrero S. (2015). Barriers to access for severe acute malnutrition treatment servies in Pakistan and Ethiopia: a comparative qualitative analysis. Public Health Nutr, 18(10), 1873-1882. doi:10.1017/S1368980014002444

Rogers E, Myatt M, Woodhead S, Guerrero S & Alvarez JL. (2015). Coverage of community-based management of severe acute malnutrition programmes in twenty-one countries, 2012-2013. PLoS One, 10(6), e0128666. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0128666

Tesfai C, Marron B, Kim A & Makura I. (2016). Enabling low-literacy community health workers to treat uncomplicated SAM as part of community case management: innovation and field tests. Retrieved from www.ennonline.net/fex/52/communityhealthworkerssam