How countries can reduce child stunting at scale: lessons from exemplar countries

Summary of research1

Location: Nepal, Ethiopia, Peru, Kyrgyz Republic, Senegal

What we know: Global levels of stunting remain unacceptably high; progress is needed to reduce national stunting prevalence in order to achieve the World Health Assembly and Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) targets.

What this article adds: Several countries have dramatically reduced child stunting prevalence with or without the closing of population inequalities. The progress made by five exemplar countries was reviewed and synthesised to provide guidance on how to accelerate reductions in national stunting prevalence. Despite significant heterogeneity and differences in context, interventions unrelated to health and nutrition contributed to about 50% of child stunting reduction in each country while interventions from the health and nutrition sectors contributed to about 40%. An improved classification of nutrition actions, presented in this article, allows countries to effectively plan, prioritise and invest in strategies that will lead to the intended population level nutrition-related outcomes. Clearly demarcating responsibilities by sectors to deliver on their core sectoral mandates with an equity lens also has strong potential to build an enabling environment for nutrition at the household level.

Although the global prevalence of childhood stunting has declined over previous decades, it remains unacceptably high. The progress made by five exemplar countries where stunting prevalence has dramatically reduced, despite population inequalities, was reviewed and synthesised to provide guidance on how to accelerate reductions in national stunting prevalence. Exemplar countries are defined as those that have an outsized reduction in child stunting prevalence in a 15 to 20 year period relative to economic growth and include Peru, Kyrgyz Republic, Nepal, Ethiopia and Senegal. Methods included descriptive analyses of cross-sectional data, a deterministic analysis of quantitative drivers of change in linear growth, country-level stakeholder interviews, a review of policy and programme evolution over the time period of study and a resulting integrative analysis of insights.

The review of the burden, trends and distribution of child stunting prevalence revealed similar progress in stunting reduction across the exemplar nations despite very diverse contexts. Gains in overall development, employment, literacy, female empowerment, household conditions, health and out-of-pocket spending, health worker availability and maternal and child health (among other indicators) were observed across the exemplar countries. Strong stunting reduction was coupled with entire child stunting distribution shifts in the exemplar countries suggesting that child growth faltering is reducing at a national level. Interestingly, wealth inequalities did not reduce and, in fact, even widened in Nepal, Senegal and Ethiopia over time. Child stunting compared with age curve analysis suggests that Ethiopia, Nepal and Kyrgyz Republic have had substantial improvements in length at birth which could indicate improvements in maternal nutritional status and maternal and newborn care. Peru and Senegal had dramatic flattening of the stunting curve over time for children aged 6 to 23 months which suggests improvements in disease prevention and management, better dietary practices and improved household environments.

When examining quantitative drivers, the multivariate analysis models could explain 72–100% of mean stunting improvement across the countries. Despite significant heterogeneity and differences in context, interventions unrelated to health and nutrition contributed to about 50% of child stunting reduction in each country while interventions from the health and nutrition sectors contributed to about 40%. Some of the gaps related to “unexplained” fractions in Kyrgyz Republic, Senegal and Nepal are likely related to food security/dietary intake or maternal newborn healthcare or nutrition improvement because proxies for these were lacking in those countries. Improvements in maternal education, maternal nutrition, maternal and newborn care and reductions in fertility/reduced inter-pregnancy intervals were strong and common contributors to change. Some variations in drivers were evident across the countries examined, a finding that largely resulted from differing country contexts and status at baseline. For example, reduced open defecation contributed to 17% of the change in stunting in Ethiopia whereas improved Water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) practices did not emerge as a factor in Kyrgyz Republic.

Key policy, strategy and programmatic investments adopted by countries to reduce child stunting had several commonalities. Effective initiatives included health and nutrition interventions addressing the immediate determinants including those to improve maternal nutrition and newborn outcomes, promote early and exclusive breastfeeding and improve complementary feeding practices. Investments in improving reproductive health practices were also important for increasing contraceptive use, delaying first pregnancy and increasing birth spacing. Other sectoral strategies, such as those to improve economic conditions, parental education and WASH, also played a key role in addressing underlying determinants of child growth. Pivotal to gains were high-level political and donor support as well as sustained financing to improve child health and nutrition overall, investments in granular data, national capacities for monitoring and decision-making and capacities for programme implementation at scale.

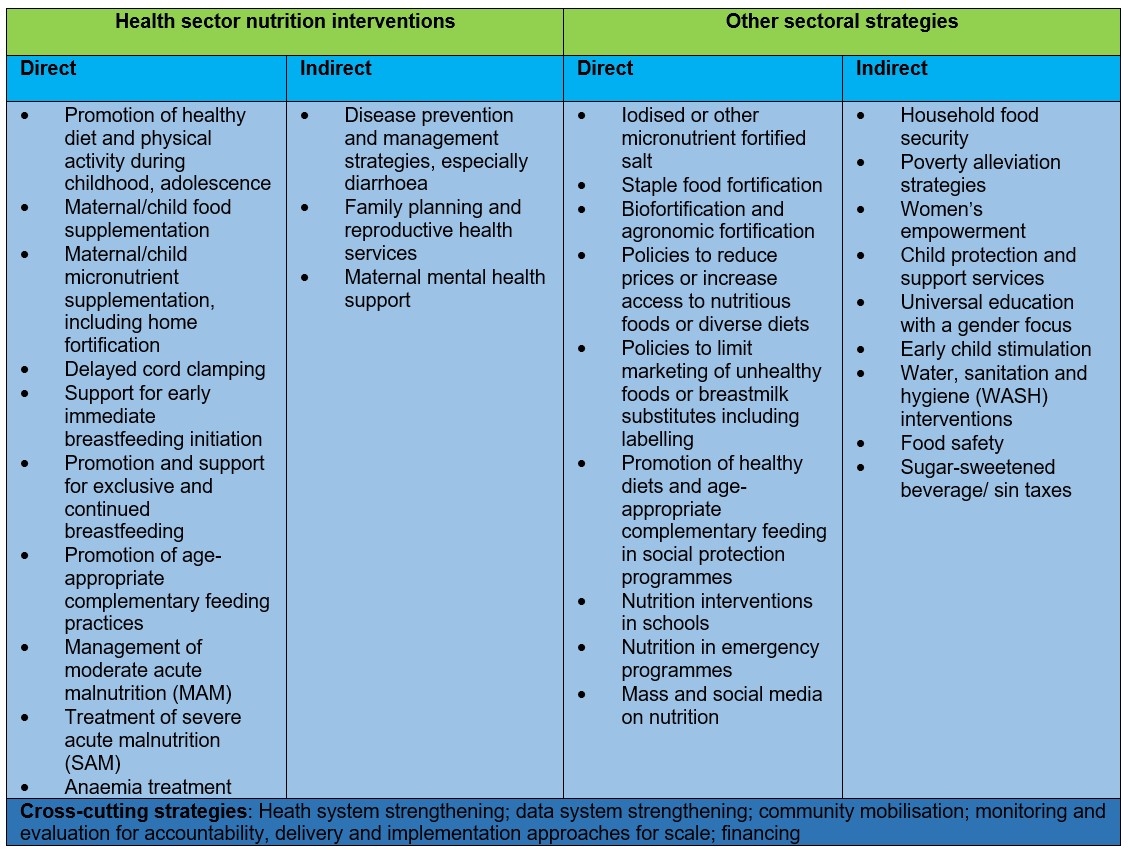

The authors propose a new framework for categorising drivers of change when mapping child stunting causal pathways and planning interventions and strategies to accelerate stunting reduction. They suggest that nutrition interventions are organised as direct/indirect and inside/outside the health sector. This is to replace the nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive divide that emerged from the 2013 Lancet series on maternal and child nutrition. In this new framework (Figure 1), direct or indirect nutrition interventions within the health sector are considered separately alongside other sectoral approaches that aim to improve nutrition in a more supportive manner. Direct nutrition interventions, which in this framework extend beyond stunting reduction to encompass multiple nutrition outcomes and conditions such as reduction of wasting and anaemia, are nearly synonymous with those that were previously named nutrition-specific. However, several approaches that were previously deemed nutrition-sensitive are better reclassified as indirect nutrition strategies (e.g., disease prevention and management and reproductive health). Other interventions, which also contain direct and indirect actions, fall into the other sectoral strategy categories including agriculture and food security, social safety nets (such as conditional cash transfers) and other poverty alleviation strategies, promotion of women’s empowerment, child protection, education and WASH. Within this schema, direct interventions addressing the immediate determinants of all forms of child undernutrition and indirect interventions (that are both inside and outside the health sector) work to alleviate the more distal, underlying determinants. Not all indirect interventions explicitly include a nutrition focus but sectoral agendas can firmly and positively address the underlying determinants of child growth when implemented with a focus on closing social and geographic equity gaps.

A two-phased roadmap is proposed by the authors for reducing child stunting at scale: 1) policy and investment cases for reducing child stunting beginning with a robust diagnostic comprised of a situational analysis, stakeholder consultations and identification of interventions and delivery mechanisms and 2) strengthening of delivery systems and implementation of scaled-up actions identified through the iterative process in Phase I in both the health and nutrition sectors and non-health sectors.

The authors propose that this improved classification of nutrition actions will allow countries to effectively plan, prioritise and invest in strategies that will lead to intended population level nutrition-related outcomes. Given the complex and multi-causal nature of suboptimal growth and development, multi-sector approaches are generally preferred. However, clearly demarcating responsibilities by sectors to deliver on their core sectoral mandates with an equity lens also has strong potential to build an enabling environment for nutrition at the household level.

Figure 1: Conceptual framework for interventions related to child and maternal undernutrition

Subscribe freely to receive Field Exchange content to your mailbox or front door.

Endnotes

1 Zulfiqar A Bhutta, Nadia Akseer, Emily C Keats, Tyler Vaivada, Shawn Baker, Susan E Horton, Joanne Katz, Purnima Menon, Ellen Piwoz, Meera Shekar, Cesar Victora, Robert Black, How countries can reduce child stunting at scale: lessons from exemplar countries, The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Volume 112, Issue Supplement_2, 1 September 2020, Pages 894S–904S, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqaa153