Embedding nutrition within the Farmer Field School approach: Experiences from Malawi

Mary Corbett is the Global Nutrition Advisor at Self Help Africa, Ireland

Virginia Mzunzu Kwizombe is a former Nutrition Advisor at Self Help Africa, Malawi

Dalitso Baloyi is a Senior Researcher at DMT Consult, Lilongwe, Malawi

Ulemu Priscilla Chiyenda is a Nutritionist and Researcher at DMT Consult, Malawi

The authors would like to thank the European Union, which funded the programme and the accompanying research component.

Key messages:

- The Farmer Field School (FFS) approach strengthens technical capacity at community level and empowers farmers to make decisions on the best crops to grow according to the local context. Nutrition may be included within FFS as a ‘special topic’.

- Results from a robust endline evaluation of Self Help Africa (SHA)’s five-year programme in Malawi demonstrated the effectiveness of concerted efforts to improve the overall nutrition sensitivity of the FFS approach. FFS participants were three times more likely to meet their minimum dietary diversity requirement than non-FFS participants (OR = 3.592, p < 0.001).

- Nutrition needs to be embedded within the FFS approach, and not just included as a ‘special topic’. Activities that were found to be particularly useful were strengthening sector integration, the use of context-specific resources and adaptations, addressing gender norms and embedding market analysis.

A better project

The Better Extension Training Transforming Economic Returns (BETTER) project was implemented by SHA Malawi between 2018 and 2022. Funded by the European Union, BETTER was delivered to 10 districts of Malawi - Chitipa, Karonga, Mzimba, Nkhatabay, Nkhotakota, Salima, Kasungu, Thyolo, Chiradzulu and Mulanje. The programme was implemented by a consortium of four partner organisations: SHA (Lead Agency), Plan International Malawi, Action Aid Malawi and the Evangelical Association of Malawi. The objective of the project was to increase resilience and to improve the food, nutrition and income security of 402,000 smallholder farmers through 13,400 FFSs (Box 1).

The BETTER programme promoted nutrition-sensitive agriculture by integrating nutrition education within all value chain activities in FFS. This approach ensured that participants gained knowledge of how to link the production of more diverse crops, as well as improved harvest and post-harvest practices (including storage), with improved utilisation of crops using locally developed recipes and cooking demonstrations, thereby facilitating the increased consumption of more diverse diets in a sustainable way.

Box 1: The FFS approach (FAO, 2023)

The FFS approach was developed in Indonesia in the late 1980s by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), together with national stakeholders, especially the Ministry of Agriculture. FFSs offer an alternative to top-down approaches, which have often proved ineffective. The FFS approach strengthens technical capacity at community level and empowers farmers to make decisions on what crops to grow that are context specific. Crop trials using different agriculture practices and pest management help farmers make decisions on the best crops and varieties to grow, rather than decisions being made at central level.

As part of the FFS approach, groups of 20-25 farmers (ensuring a gender balance) test conventional local practices for growing specific crops compared to national/global standard practices over a planting season, with a strong focus on integrated pest management. Weekly meetings are held to monitor successes and failures. Crops from different trial sites (different types of seed, fertiliser amounts, intercropping, different types of pest management) are viewed and measurements taken to monitor crop growth, disease and (at harvest time) crop yields and produce quality. Records are kept on a weekly basis, and the results inform decisions going forward. Over time the approach has broadened to include a focus on "special topics" such as nutrition, HIV and gender, depending on context and needs. Currently, each FFS meeting includes at least three activities: an agro-ecosystem analysis, a ‘special topic’ and a group dynamics activity. Under the BETTER programme, although the main focus was on agro-ecological practices with nutrition considered to be a ‘special topic’, overall efforts were made to increase the nutrition sensitivity more generally across the whole approach.

When establishing FFSs, the FAO is responsible for training Master Trainers and Community-Based Facilitators in the approach. Master Trainers - often government agriculture extension staff - support 30 Community-Based Facilitators, who each form an FFS. The implementing partners at district/community level are responsible for further training and monitoring of FFS activities, including collaboration with district level personnel from different ministries.

SHA’s approach to strengthening nutrition within agriculture programmes

Historically, nutrition has not been embedded within agriculture programming. However, over the past 10 years, evidence has suggested positive benefits of ensuring that the agriculture sector incorporates a nutrition-sensitive approach, including increasing the quantity and diversity of nutritious crops produced, in combination with a strong nutrition behavioural change component to improve dietary diversity (Ruel et al, 2018). Considering this, SHA aims to include nutrition within agriculture and enterprise programming, where possible. Within the BETTER FFS programme in Malawi, guidelines and standard operating procedures for nutrition-sensitive agriculture were developed. Sensitisation and training was then delivered by the SHA nutritionist to SHA and implementing partner staff, as well as to Ministry of Agriculture colleagues at district and regional level.

As part of the programme, nutrition education focused on promoting crop diversification using a food availability calendar (Box 2), dietary diversity (the promotion of Malawi’s six food groups) (Ministry of Health, 2007), improved infant and young child feeding practices, and food budgeting and planning. The promotion of nutrient-dense crops such as groundnuts, beans, soybeans and orange-fleshed sweet potatoes was a core component to increase the availability of more nutritious foods at household and community levels. The programme also provided information on maximising nutrient yields, food processing and cooking demonstrations to ensure better food utilisation (combining foods and food groups). Improved hygiene practices were also promoted, given their documented links with nutritional status (Shrestha et al, 2020), as were strategies for post-harvest management using improved storage.

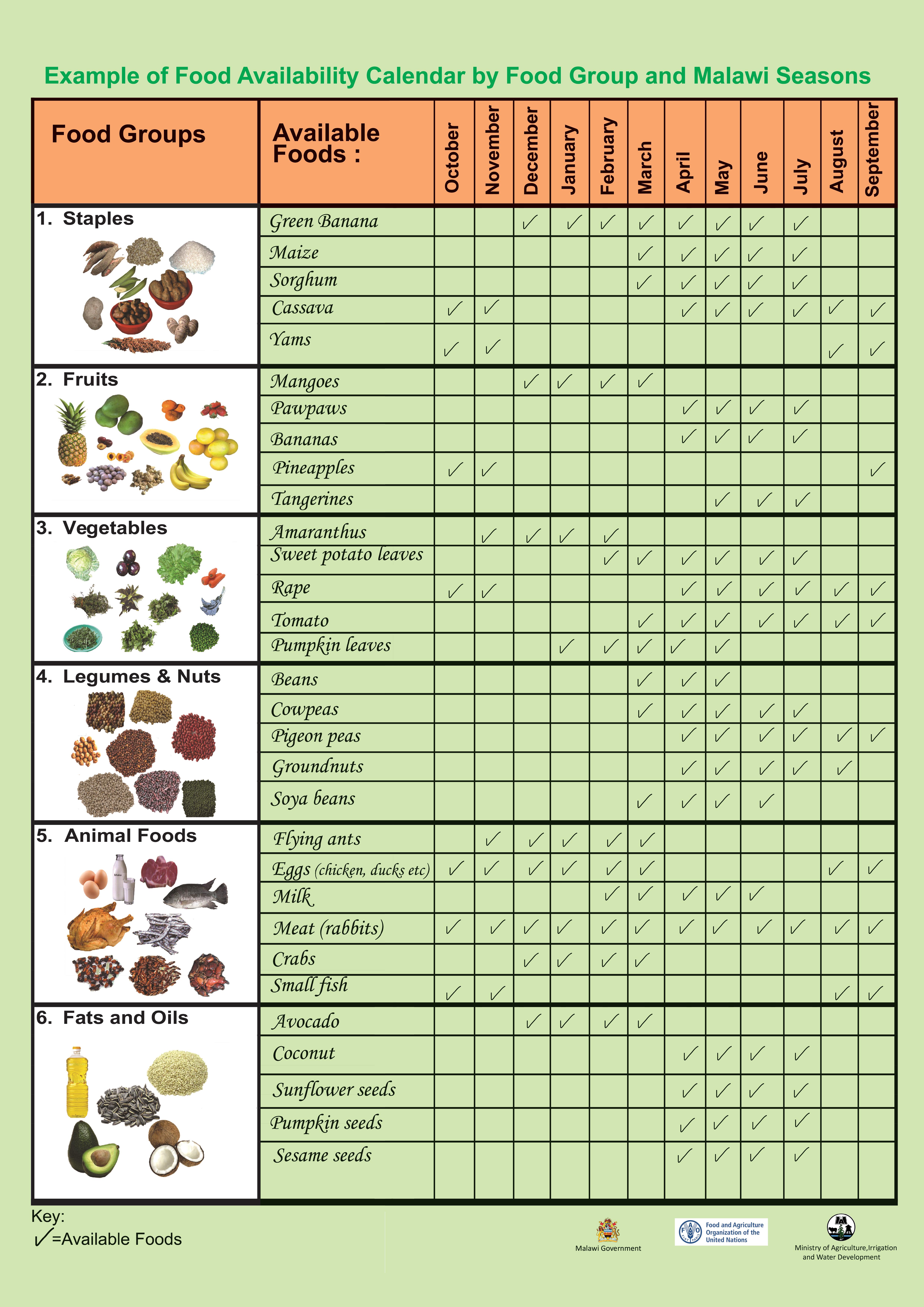

Box 2. Food availability calendar

When completed, the food availability calendar identifies the gaps and times of the year when foods from certain food groups are not available or limited. Discussions can then be had, and decisions made, on how to address these gaps - for example, what foods can be grown to reduce that seasonal gap.

Example of a completed food availability calendar:

Research methodology

In Year 4 of the programme, research was conducted by two external consultants with support from SHA Malawi to understand how well the nutrition components were embedded within the FFS approach, how successful uptake of knowledge and behavioural change was and what lessons could be learnt for future programming (Baloyi et al, 2022).

The operational research incorporated mixed methods approaches to collect qualitative and quantiÂtative data. Participatory research approaches were used to understand the overall functionality, effectiveness, efficacy and short-term and long-term nutritional benefits of FFSs, as well as to inform recommendations. Data were collected through household surveys, key informant interviews and gender-disaggregated focus group discussions (FGD).

In total, a regionally representative sample of 225 FFS participants and 76 non-FFS participants were included in this research from three BETTER programme disÂtricts: Karonga, Thyolo and Salima. FGDs involving FFS participants only took place in Kasungu and Mzimba South due to cost and logistics constraints. A matched case control study design was used, where data were collected, analysed and interpreted for those participating in the FFS (case) compared to data for those not participating in the FFS (control).

Effectiveness of the approach

Nutrition integration within FFSs

- Across the three districts, all nutrition education sessions were facilitated by Master Trainers and Community-Based Facilitators, who are normally more knowledgeable and better versed in agriculture (rather than nutrition) content. There was limited involvement of key nutrition stakeholders, such as health workers and cluster leaders.

- There was variation in the frequency and timing of training on nutrition topics/sessions within FFS. This was largely a result of the different competing interests and expertise of Master Trainers and Community-Based Facilitators, as well as of the lack of a uniform FFS curriculum.

- When considering gender dynamics, there was a divide between women and men’s responsibilities and workload, especially in terms of nutrition and preparation of meals. In cases where there were potential economic benefits, for example related to juice making in Salima district, men were more interested in participating in the interventions.

"Sometimes some of the meals for demonstration involves pounding of groundnuts for nsinjiro (seasoning), and this is not what most of us men are used to do." - FGD, Mkanakhoti, Kasungu District

Impact of the FFS approach on nutrition outcomes

"We have learnt of food groups and examples of foods that we should be eating to have balanced diets." - FGD, Mpata Karonga

- Compared to non-participation, participation in FFS was associated with high levels of adoption of improved nutrition and water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) practices at household level. FFS participants were more likely than non-participants to have a backyard garden, to own livestock and to have fruit trees around their homes.

- FFS participants were three times more likely to meet their minimum dietary diversity requirement than non-FFS participants (OR = 3.592, p < 0.001).

- There was a significant increase in joint decision-making (by women and men) regarding access to, and control of, backÂyard gardens, what foods were consumed and how to use the proceeds from the sale of crops/livestock among FFS participants (63.1%) as compared to non-FFS participants (36.9%).

Winaka Amina produces eggs commercially on her small farm in Balaka district. Malawi © Self Help Africa

Discussion

Although the linkages between agriculture and nutrition are complex, evidence to date indicates that integrating nutrition education and crop diversification into agriculture programmes can improve dietary diversity and other nutrition outcomes (Pandey et al, 2016). Particularly in rural communities, what is grown determines what is eaten. Thus, building knowledge on what to grow and how best to harvest, store and utilise foods - and why - should contribute to improved dietary diversity at household level.

Findings from the BETTER programme indicated that FFS participants were three times more likely to achieve minimum dietary diversity than non-participants. One caveat to these promising results is that, as with all findings based on household surveys, they are based on reported rather than observed intakes: FFS participants may be more likely to report what they know they should be eating than non-FFS participants. This being said, FFS participants were more knowledgeable regarding good nutrition and WASH practices, and were more likely to have homestead gardens, fruit trees and own livestock, all of which are factors that can contribute to improved dietary diversity.

Based on our experience and the results from a study conducted in Uganda and Rwanda in 2014 (Nafula-Kuria, 2014), the integration of nutrition within the FFS approach still has limitations and constraints. The following are crucial steps to take towards achieving better outcomes for nutrition within the FFS approach.

Ensure nutrition is a core component of the FFS curriculum

Currently, nutrition is considered a ‘special topic’ within the FAO FFS training curriculum, but consideration should be given to making it a core component, since sufficient evidence exists regarding the benefits of including nutrition components within agriculture programmes.

Rather than comprising a one-off training session, nutrition should be embedded throughout FFS training. It is also important to highlight how improved agriculture practices, including climate smart agriculture,1 can positively impact on nutrition. For example, activities such as intercropping with pulses positively impacts on soil fertility and also benefits human nutrition via increased access to pulses for both consumption and income generation.

Strengthen sector integration

For nutrition to become a core component during the training of Master Trainers and Community-Based Facilitators, it may be beneficial to develop training materials within the main curriculum that draw on technical expertise in health, nutrition and WASH from Ministries of Health. Currently, in Malawi, the Ministry of Health does not play and active role in the FFS approach. Increased engagement would support improvements in sector integration.

Including a basic WASH component within nutrition education/promotion facilitated increased adoption of these practices among the FFS participants.

Use context-specific/locally developed resources to greater effect

The Ministry of Agriculture, Irrigation and Water Development, together with the FAO and funded by the Government of Flanders, produced a Nutrition Handbook for FFS in 2015 (Ministry of Agriculture, Irrigation and Water Development, 2015). While this resource was revised during the programme implementing period, it was not shared with Master Trainers and SHA staff. This would have been a valuable resource for the Master Trainers and Community-Based Facilitators and should potentially have been translated into the major Malawian language (Chichewa). This is an example of a case where a resource is developed but not used for various reasons, including lack of awareness of the resource, perceived need to produce tailored material for individual programmes and the unavailability of material in local dialects.

Basic training materials, such as the seasonal food availability calendar, the malnutrition problem tree and the Malawi food group chart, were translated into local dialects and made available to members at FFS level. This was important for accurate sharing of basic nutrition information and for participants to be able to refer to the material when necessary. Cooking demonstrations also supported knowledge retention through practical hands-on learning, with community participatory engagement.

Context-specific adaptations can optimise results

Within the FFS approach, the farmers decide which crops to focus on during trials. However, under the Malawi FFS programme, a majority of the farmer groups focused on maize (the main staple). To ensure farmers considered other crops and therefore produced a more diversified harvest, it was decided that farmers would also have to trial a less common crop within the FFS. The programme was successfully adapted to reflect this by conducting trials on crops such as sorghum, cassava and cowpeas, and also by trialling drought-tolerant varieties as part of the intervention.

The Fall Armyworm - an invasive species with broad geographical coverage and a propensity for crop destruction - became a major pest during the programme. To address this, trials were conducted in different parts of Malawi using four different options: synthetic pesticides, hand picking and two types of botanical pesticides - fish soup and chilli and tobacco pellets crushed and made into a spray with detergent. The latter was identified as the most successful approach in terms of availability, affordability and results. This shows how flexible the FFS approach can be to changes in local context.

Embed a stronger market analysis

Moving forward, it is valuable to embed a stronger market element at the start of an FFS programme. Ideally, market surveys should be conducted to understand the baseline situation, and a plan should be developed for strengthening the various elements of the value chain so that increased production can increase access to markets and income, and ultimately consumption within the household.

Members of Chimankhuku Women's Poultry Club, selling chickens at their local market. Malawi © Self Help Africa

Gender dynamics

Gender was a cross-cutting issue within the BETTER FFS programme. Considerably higher levels of joint decision-making were reported in FFS households as compared to non-FFS households in two of the three districts surveyed - Thyolo (62% and 38% respectively) and Salima (57% and 43% respectively). In the third district (Karonga), there was no difference in level of joint decision-making.

Interestingly, in this district, a particular cultural tenet holds that most decisions should be made by males/husbands. This suggests more focused, context-specific efforts are needed to improve gender dynamics where gender norms are more strongly entrenched. Improving women’s empowerment in agriculture is an important pathway through which nutrition outcomes can be improved.

Conclusion

Overall, strengthening the nutrition component of the FFS (including WASH) showed great promise in contributing to improved food and nutrition security at community level, particularly in rural agriculture communities where chronic malnutrition remains a challenge. Increasing the production of more diverse crops and improving harvest and post-harvest handling, including storage and better combination and utilisation of foods, is a ‘win’ for all. It is important to continue embedding nutrition components within agriculture interventions to support poor rural communities in better understanding how changes to agriculture production can improve access to diverse nutritious diets and generate incomes from excess resources/harvests. Ensuring that nutrition is better integrated as a core component of the FFS approach is a priority.

For more information, please contact Mary Corbett at mary.corbett@selfhelpafrica.net

References

Baloyi V, Mzunzu K, Ulemu C, et al (2022) Operational Research on Integrating Nutrition in Farmer Field Schools. Self Help Africa. https://selfhelpafrica.org/ie/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2022/06/FINAL-Operational-Research-Integrating-Nutrition-in-FFS-web-short-version.pdf

FAO (2023) Global Farmer Field School Platform. www.fao.org/farmer-field-schools/ffs-overview/nutrition/en/

Ministry of Agriculture, Irrigation and Water Development (2015) Nutrition Handbook for Farmer Field Schools. https://www.fao.org/farmer-field-schools/ffs-overview/nutrition/en/

Ministry of Health (2007) National Nutrition Guidelines for Malawi. https://cepa.rmportal.net/Library/government-publications/National%20Nutrition%20Guidelines%20for%20Malawi.pdf

Nafula-Kuria, E (2014) Integrating nutrition in Farmer Field Schools - Lessons learned in Eastern Africa. https://agrilinks.org/sites/default/files/resource/files/MEAS%20EVAL%20Full%20Report-%20Integrating%20Nutrition%20in%20FFS%20in%20Eastern%20Africa%20-%20Nov%20%202014.pdf

Pandey VL, Mahendra Dev S & Jayachandran U (2016) Impact of agricultural interventions on the nutritional status in South Asia: A review. Food Policy, 62, 28-40.

Ruel MT, Quisumbing AR & Balagamwala M (2018) Nutrition-sensitive agriculture: What have we learned so far? Global Food Security, 17, 128-153.

Shrestha A, Six J, Dahal D, et al (2020). Association of nutrition, water, sanitation and hygiene practices with children’s nutritional status, intestinal parasitic infections and diarrhoea in rural Nepal: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 20, 1241.

1 Climate smart agriculture aims to increase agriculture productivity, improve adaptation and resilience to climate change, and mitigate the impacts of climate change through reducing greenhouse gas emissions.