Community mass MUAC screening in emergency contexts: Lessons from Afghanistan

Beka Teshome Bongassie Deputy Nutrition Cluster Coordinator Afghanistan, Action Against Hunger

Koki Kyalo Nutrition Cluster Coordinator Afghanistan, UNICEF

Dr Abdul Basir Rasuli Senior Monitoring and Evaluation Officer, Afghanistan Ministry of Public Health

Tomás Zaba Nutrition Specialist, IPC Global Support Unit, Italy

Mohammad Karim Mirzad Senior Assessment Analyst, REACH Initiative Afghanistan

What we know: Nutrition assessments are essential for understanding nutritional needs, identifying high burden areas, and estimating resource requirements.

What this adds: In resource-limited and complex settings, mass MUAC (mid-upper arm circumference) screening can be an effective tool for assessing nutritional needs, monitoring coverage, and identifying and referring cases. This mass screening exercise successfully brought together 21 partners across 17 provinces and was completed within three months.

Afghanistan has endured years of conflict, natural hazards, and climate-related shocks, profoundly affecting its citizens. These challenges have hindered economic growth and restricted access to essential services (OCHA, 2024). Against this backdrop, malnutrition is common, with estimates indicating that, in 2022, approximately one in two children would develop wasting. In 2022, a national Standardised Monitoring and Assessment of Relief and Transitions (SMART) survey was conducted, which showed that 10.3% of children aged 0-59 months were suffering from wasting, of which 1.5% had severe wasting (Afghanistan Nutrition Cluster, 2023).

Community mass MUAC screening

Since 2022, no additional SMART surveys have taken place, and nutritional planning has largely relied on routine data collection through the Community Nutrition Sentinel Surveillance (C-NSS) platform. However, 17 provinces in the country are without C-NSS. In a dynamic, ever-changing context like Afghanistan, the timely identification of emerging nutrition crises is crucial. Without the ability to conduct regular population-representative nutrition surveys or use sentinel surveillance systems, processes to utilise community mass MUAC screenings have been developed. This approach enables regular, resource-efficient, active screening to provide timely understanding of the current nutrition situation. Additionally, such surveys can assess key indicators, including geographic coverage and treatment programme admission rates, as well as inform resource allocation to ensure the areas of highest need are suitably resourced.

In Afghanistan, community mass screening was proposed to support the nutrition cluster’s key priorities, which are to assess the current national nutritional situation and to address declines in programme admission rates for the management of wasting.

Assessing current nutritional status

The primary goal of the mass MUAC screening was to collect updated data on the nutritional status of children aged 6-59 months. Specific provinces were targeted due the absence of data or concerns about data quality, enabling a better understanding of the wasting prevalence in these areas and identifying geographic areas with high rates of wasting to target interventions. This subsequently informed the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification Acute Malnutrition (IPC-AMN) analysis and supported estimations of ‘People in Need’ (PiN) (defined as people who are wasted and in need of lifesaving treatment or nutritional support within the year) to inform nutrition cluster priorities.

Addressing declines in admissions for wasting supplementation and treatment

From January to July 2024, the number of children enrolled in wasting supplementation and treatment services declined by 16.7% compared to the same period in 2023. However, given Afghanistan’s rapidly worsening humanitarian situation, it was unlikely that this was due to a reduction in actual cases. Suboptimal screening at health facilities was potentially a contributing factor, as analysis of outpatient department visits for children aged under five years in 2024 indicated that nearly 45% of children were not screened for their nutritional status. The mass screening could support with identifying and referring children with wasting, thereby contributing to improving the coverage of interventions in targeted areas.

Methodology

Mass MUAC screening planning

Planning for the mass screening began in July 2024 and included the analysis of admission and screening data, followed by a review and approval of the approach by the Afghanistan Information Management Technical Working Group (AIM-TWG). In August, partner mapping was conducted by updating the ‘who, what, where, and when’ of organisations (4Ws). At the same time, subnational coordinators discussed the approach at regional levels to orientate partners on screening methods. The mass screening exercise was carried out in two phases: 12 provinces in phase one (conducted in August) and five provinces in phase two (in September), followed by data analysis. The timing of the mass screening coincided with the typical ‘peak’ season for wasting admissions. The exercise concluded with the findings being validated by the AIM-TWG.

Sampling procedures

In each province, a minimum of three districts were purposively selected, based on the availability of functional health and nutrition treatment sites (both mobile and fixed) and access to nutrition services in underserved areas, as well as districts affected by floods or other shocks. Within each selected district, villages were further chosen based on similar criteria. In each selected village, all eligible children were screened.

The screening was conducted in convenient and accessible locations such as mosques, schools, and community centres. To increase participation, community sensitisation and mobilisation activities were conducted. To ensure screening quality, the screening was conducted by qualified nutrition staff, who received a one-day orientation session prior to the mass screening. The orientation covered key aspects of MUAC screening, including how to obtain accurate MUAC measurements, how to correctly assess oedema, and how to complete referral slips as well as data collection and reporting tools.

Data management and analysis

A MUAC data collection template was translated into local languages (Pashto and Dari). Data was submitted daily to the Nutrition Cluster via an Excel database for remote monitoring to check the data quality, completeness, and consistency. Records with missing or invalid information on sex, age, or MUAC measurements were excluded from the analysis.

The data’s plausibility was assessed using the SMART Initiative’s standard data quality evaluation procedures (SMART, 2017), as well as methods suggested by Bilukha and Kianian (2023).

Overall, only age-ratio tests were problematic across several provinces where there were more younger children than older children. This was adjusted for by analysing the prevalence of the respective provinces with age-weighting. The methodology and data collection were reviewed and validated by the AIM-TWG.

Findings

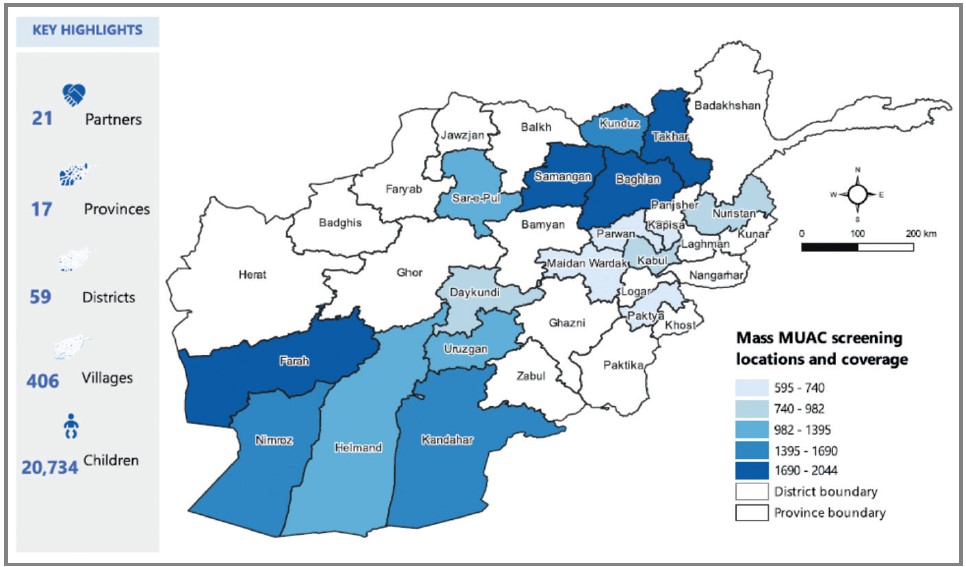

The mass screening was carried out across 17 provinces where the C-NSS was not operational (Figure 1). It targeted 59 districts and covered 406 villages, with a total of 20,734 children aged 6-59 months being screened. Twenty-one nutrition partners were involved in the screening process.

Figure 1. Mass MUAC screening locations marked in blue

Children’s nutritional status

The mass MUAC screening revealed varying rates of proxy wasting across the provinces, with the highest rates observed in Helmand at 22.3%, followed by Sar e Pul at 17.2%. In total, the prevalence of wasting exceeded 10% in nine provinces. The lowest wasting prevalence rates were recorded in Wardak (5.6%), Kapisa (7.7%), and Paktia (7.8%). These findings highlight significant provincial variation in wasting prevalence, with several provinces experiencing wasting prevalence well above emergency thresholds for MUAC of 10-14.9%. This indicates an urgent need for targeted nutrition interventions.

Coverage insights

The mass screening also provided findings on programme coverage. To estimate proxy coverage rates, the caretakers of wasted children identified were asked whether or not the child had been enrolled in an outpatient therapeutic programme (OTP) or a therapeutic supplementary feeding programme (TSFP). Of the total 20,734 children screened, 609 cases of severe wasting and 2,146 cases of moderate wasting were identified. Of these, 342 severe and 1,232 moderate wasting cases were not yet receiving nutrition treatment or supplementation, indicating an estimated coverage of 47% for OTPs and 43% for TSFPs respectively.

OTP coverage was below the recommended 50% threshold in several provinces, ranging from 33.3% in Nimroz and Takhar and 38.5% in Kandahar to 71.4% in Kapisa and 63.6% in Paktia. Similarly, TSFP coverage varied, with some provinces falling far below the recommended standards for rural contexts. For instance, Kabul’s coverage was very low at 19.2%, while Nimroz and Sar-e-Pul also reported low rates of 30.6% and 28.0%, respectively. Provinces such as Kunduz (60.2%) and Baghlan (57.8%) showed relatively higher coverage, although still below ideal targets.

MUAC prevalence by age

The analysis of MUAC prevalence by age revealed that wasting peaked during the first two years of life, consistent with previous SMART survey findings. This finding supports the established understanding that the first 1,000 days represent a critical window of opportunity for improving a child’s health and wellbeing.

Referral and admission outcomes for children with wasting

During the mass screening, wasted children that were not yet receiving wasting treatment or supplementation were referred to the nearest health facility with a referral slip and their caregivers were counselled on the importance of these services. The children’s details were also shared with the community health programme for follow-up. Some 75% of severely wasted children referred were admitted into an OTP, ranging from 33% to 100% across provinces. The overall average number of days it took for children to be admitted following referral was 5.1 days, with significant variation across provinces from 0.9 to 28.9 days.

With those identified with moderate wasting, 76%, ranging from 40% to 100%, were enrolled into a TSFP. The average time to enrolment was approximately 5.5 days, ranging from 0.6 days to 28.3 days across the provinces.

Lessons learned

The success of this mass screening exercise highlights its value as an alternative data source for understanding an overall nutrition situation, particularly when population-level surveys, like SMART surveys, are unavailable.

The initiative demonstrated that high-quality MUAC data can be collected within a short timeframe using existing resources. Its quality was ensured by close supervision by the AIM-TWG. While the MUAC data was deemed to be acceptable, inconsistencies in age-ratio data indicated a need for further enumerator training.

The mass MUAC screening was an essential tool to assess wasting prevalence across the 17 provinces and provided valuable insights into the overall nutrition situation. Data from the mass screening became a crucial resource for the IPC-AMN analysis conducted in October 2024. This analysis was not possible the year before due to a lack of available data. The screening exercise also supported PiN estimates that informed the 2025 Afghanistan Humanitarian Needs and Response Plan (OCHA, 2025). Interestingly, results from the mass screening aligned with the PiN estimates on the expected number of wasted children, indicating that different assessment methods showed similar results. It remains important to continue monitoring how different data collection approaches influence estimates of wasting prevalence and PiN over time.

Additionally, the mass screening data enhanced understandings of programme coverage, enabling the identification of service delivery gaps. This information was crucial for nutrition cluster partners and donors to suitably allocate resources based on need, enhancing programme impact. In the absence of routine coverage surveys, the mass MUAC screening facilitated referral to nutrition interventions and helped to reach those most in need.

By identifying a high number of wasted children in a timely manner and referring them for nutritional support, the mass screening exercise contributed to improved access to nutrition supplementation and treatment. Following the mass screening, health facilities, to which children were referred, reported that they were able to manage the influx of new cases without any overcrowding. However, several factors continue to affect access and the utilisation of nutrition services for women and children. For example, the need for a male guardian (a mahram) to accompany women, including female health workers, when leaving the home remains a barrier to accessing care. Additionally, a previous strategy was discontinued that focused on larger cities, like Kabul, and has led to a shortage of human resources at health facilities, contributing to a decline in admissions. The presence and capacity of NGOs vary across provinces, and this is likely to have also impacted coverage.

Furthermore, due to funding cuts and government reprioritisation, approximately 52% (~340) of mobile health and nutrition teams and over 450 TSFP sites throughout the country had to close in 2024, significantly impacting hard-to-reach areas and contributing to the decline in admissions. Provinces like Nuristan and Takhar were particularly impacted by these closures, which contributed to the low admission rates of referred children due to long travel distances and geographical barriers to accessing health facilities. It is expected that, in 2025, even more TSFPs and OTPs will need to close due to the impact of the USAID funding freezes. Initial estimates note that 246 OTPs and 42 TSFPs had already closed in February, impacting over 4,000 children and 2,000 women.

Conducting the screening exercise across 17 provinces and with 21 partners was enabled through several key factors. Firstly, subnational cluster coordinators played a crucial role in coordinating regional stakeholders, as well as cluster partners present at both provincial and district levels. Additionally, strong leadership from the nutrition department within the Ministry of Public Health at national level streamlined the process and facilitated the involvement of experienced nutrition staff, who were instrumental in ensuring data quality. A major learning was the importance of early planning at national level for such a large-scale initiative. This included ongoing engagement with all stakeholders. Moreover, conducting community sensitisation and mobilisation activities helped high levels of caregiver participation in the mass screening.

Despite its success, the planning and implementation of the mass screening faced several limitations, collectively reducing the coverage of the screening initiative. Many partners as well as government departments were unfamiliar with the concept of mass MUAC screening compared to established methodologies, such as SMART surveys. Thus, significant coordination and sensitisation efforts were required, reducing the time available for implementation and data collection, resulting in small sample sizes in certain districts. Additionally, access to remote areas posed a significant challenge, often due to a lack of roads. In some areas, low community awareness affected caregiver participation. Furthermore, given the focus on MUAC measurements, weight-for-height measurements were not collected, and some wasted children may have been missed in the process.

Conclusion and recommendations

The mass screening was planned and conducted relatively quickly, utilising existing resources and the capacity of Nutrition Cluster partners across the 17 provinces. The widespread presence of Nutrition Cluster partners ensured that the screening occurred effectively and efficiently without the need for additional resources. By regularly conducting such screenings, the Nutrition Cluster and its partners can be better positioned to improve the reach of nutrition programmes, assess the current nutrition situation, and respond promptly to emerging needs and trends.

A mass screening does not replace routine screenings by facility-based healthcare workers and community health workers. However, in a rapidly changing context like Afghanistan, integrating quarterly mass screening into national and regional nutrition response plans and programmes is a helpful tool to increase monitoring trends in the nutritional situation in the absence of standard survey data. The mass screening can also provide a proxy estimate of coverage for identifying and prioritising geographical areas with significant gaps and needs, thereby supporting targeting nutrition interventions and strategic resource allocation.

For more information, please contact Beka Teshome Bongassie at nut-clusterco@af-actionagainsthunger.org

References

Afghanistan Nutrition Cluster (2023) Afghanistan National SMART Survey Report (April-October 2022)

Bilukha O & Kianian B (2023) Considerations for assessment of measurement quality of mid-upper arm circumference data in anthropometric surveys and mass nutritional screenings conducted in humanitarian and refugee settings. January 2023. Maternal & Child Nutrition e13478

Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) (2024) Afghanistan humanitarian needs and response plan: Humanitarian Program Cycle 2025

SMART (2017) Manual 2.0. Action Against Hunger Canada and the Technical Advisory Group

About This Article

Download & Citation

Reference this page

Teshome Bongassie B, Kyalo K, Basir Rasuli A, Zaba T & Karim Mirzad M (2025). Community mass MUAC screening in emergency contexts: Lessons from Afghanistan. Field Exchange issue 75. Emergency Nutrition Network (ENN), Oxford, UK. https://doi.org/10.71744/8ktq-8594