Risk factors associated with severe acute malnutrition relapse in Sudan

Iris Bollemeijer, Senior Nutrition Advisor, International Medical Corps, USA

Jennifer Majer, Senior Advisor, – Monitoring and Evaluation and Research, International Medical Corps, USA

Shimelis Cherie, Nutrition Coordinator, International Medical Corps, Sudan

Abd Elbasit Ahmed, Associate Professor at Faculty of Public and Environmental Health, University of Khartoum, Sudan

Rania Hamid, Assistant Professor at Faculty of Public and Environmental Health, University of Khartoum, Sudan

Israa Abobaker, Lecturer at Faculty of Mathematical Science and Informatics, University of Khartoum, Sudan

Osman Fadle, Lecturer at Faculty of Public and Environmental Health, University of Khartoum, Sudan

Nazik Mustafa, Associate Professor at Faculty of Public and Environmental Health, University of Khartoum, Sudan

We would like to acknowledge the efforts of the International Medical Corps data collection team and operations staff in Sudan, as well as the support of the Ministry of Health (MoH) and the Humanitarian Aid Commission (HAC), especially Dr Nuha Salheen (National Nutrition Director, Federal MoH) and Fatima Mahmoud (Nutrition Coordinator, Federal HAC). Finally, our deepest appreciation goes to the caretakers who took the time for the interviews. This study was funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), Bureau of Humanitarian Affairs. USAID had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, or in the writing of the manuscript.

What we know: In Sudan, the onset of conflict in April 2023 exacerbated already critical levels of malnutrition. Community-based management of acute malnutrition is an effective treatment model, but limited evidence exists on post-exit outcomes and the sustainability of recovery.

What this adds: This unmatched case-control study adds evidence to potential risk factors for severe acute malnutrition (SAM) relapse. The protective role of individual counselling and breastfeeding are highlighted. The impact of other factors on relapse, such as agricultural land access and suboptimal care-seeking behaviour, need further exploration.

Malnutrition is widely recognised as the greatest single threat to public health, with nearly half of all deaths among children under five attributed to malnutrition (Victora et al, 2008). In 2021, the Global Nutrition Report (GNR) stated that 16.3% of children aged under five years in Sudan were acutely malnourished, although this figure is based on 2014 data. A survey conducted in East Jabel Mara (South Darfur) in 2020 by International Medical Corps reported a global acute malnutrition (GAM) prevalence of 18.1% and SAM prevalence of 5.3%. The onset of the conflict in April 2023 exacerbated the already critical levels of malnutrition, with a persistent risk of famine reported in October 2024. GAM prevalence among children aged under five years had reached the critical (15-29.9%) or extremely critical threshold (≥30%) in 13 localities (IPC, 2024).

In 2022, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that approximately 7.3 out of 19 million children with SAM received the appropriate treatment (WHO, 2023). Contributing to the treatment gap is the fact that a proportion of children relapse after completing treatment. The Council of Research and Technical Advice for Acute Malnutrition (CORTASAM) define relapse as “an episode of severe wasting within six months of being discharged from treatment for severe wasting”. A systematic review found that relapse cases ranged from 0% to 37% of admissions (Stobaugh et al, 2019). It also found that, there was considerable variation in both the definition of relapse and reporting across settings. Although the body of evidence related to risk factors for relapse is growing, knowledge gaps persist.

The ongoing conflict in Sudan has severely impacted health infrastructure and reduced access to treatment services (Sudan Nutrition Sector, 2024). Thus, understanding the protective and risk factors for relapse is crucial as this can inform targeted interventions to improve the sustainability of treatment outcomes.

Methods

Study design and participants

An unmatched case-control study was used to assess potential risk factors for relapse. Cases and controls were identified from outpatient therapeutic programme (OTP) registers in 30 International Medical Corps-supported facilities in Blue Nile, South Kordofan, Central Darfur, and South Darfur states of Sudan.

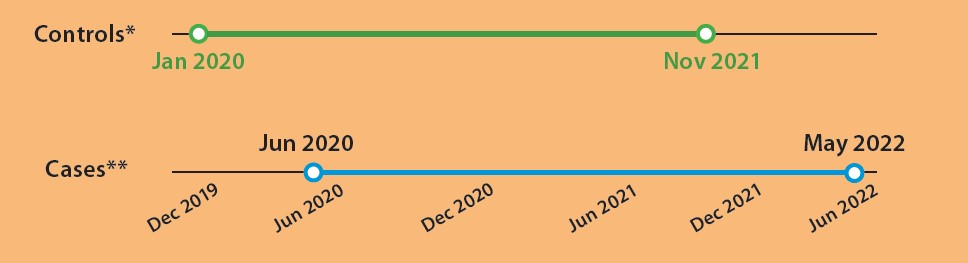

Relapse cases were defined as children aged 6-59 months enrolled in the OTP for the management of uncomplicated SAM within three months of exiting as recovered (weight for height z-score ≥-3 and/or mid-upper arm circumference ≥11.5 cm) as per the national community-based management of acute malnutrition (CMAM) guidelines. Controls were children aged 6-59 months enrolled in OTP who did not relapse within the three-month window as per the definition of the Sudan CMAM guidelines. To ensure that controls were not misclassified, an earlier enrolment period for eligibility was applied (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Eligibility period for cases and controls based on study criteria

*Controls = All children enrolled in OTP after December 2019 and discharged before November 2021 without an episode of relapse within three months of discharge.

**Cases = All children enrolled in OTP as a case of relapse after May 2020 and before May 2022.

Sampling

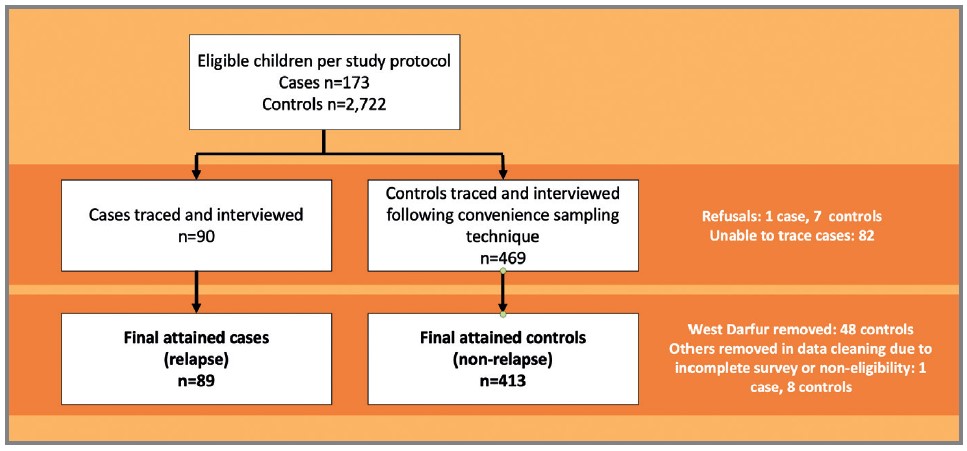

A list of all eligible children was compiled from 30 OTP registers by health facility staff, systematically reviewed, and cleaned in consultation with the research team. Controls were selected using simple random sampling. However, challenges in locating a high proportion of the randomly selected controls for interview led the research team to incorporate convenience methods. The cleaned study population frame contained 173 validated relapse cases and 2,722 controls. A sample size of 1,200 was estimated using a package in RStudio.

Data collection

Data was collected using an adapted version of UNICEF’s multiple indicator cluster survey (MICS) questionnaire, administered to children’s primary caregivers by trained community health workers after obtaining verbal consent. Interviews were conducted between June and October 2022. The questionnaire was completed by enumerators on paper and then entered into Kobo Toolbox. Data quality was subsequently reviewed on the platform.

The study considered individual- and household-level demographics and hypothesised risk factors for relapse. Six thematic areas known to affect children’s nutritional status and/or relapse were considered: general demographics, household socioeconomic characteristics and humanitarian assistance received, food security, nutrition, health, and water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH).

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using R version 4.0.5 and RStudio version 1.4.1106. Risk factors were summarised as univariable descriptive statistics and cross-tabulated against relapse status. Distributions were compared for categorical variables using a chi-square test with Rao and Scott’s second-order correction or Fisher’s exact test. Variables that were significant in univariable analyses, along with pre-selected confounders (child’s sex, age at admission, and household displacement status), were considered for inclusion in multivariable logistic regression models. These models were used to assess the independent associations between selected risk factors and the odds of relapse. Variables that were dependent on other variables (for example, time elapsed since admission with age, nutrition information source with attending infant and young child feeding (IYCF) counselling), thematically related within a sector (for example, handwashing knowledge and having sufficient quantity of water), or determined by study design (for example, state of residence) were excluded from the regression models to avoid overlapping influence and poor model fit.

Ethics

The University of Khartoum Institutional Review Board represented by the Faculty of Public and Environmental Health Research Board and the National Research Ethics Review Committee of the Sudanese Federal MoH approved this study (number 1-3-22). Written permissions were also obtained from the four state MoHs and the Sudan HAC.

Findings

Among all eligible children, the relapse rate was 6%. A total of 502 children (89 cases and 413 controls) were included in the final analysis (Figure 2). No differences were detected between cases and controls in terms of sex, age at interview, or age of child at treatment enrolment. However, a higher proportion of controls were from displaced households compared to cases (53% vs 38%, p=0.012).

Figure 2: Data collection flow chart

Crude and adjusted odds ratios (OR and aOR) were calculated to assess the relative effect size of associations between risk factors and relapse status. Only the adjusted odds ratios are presented where associations remained significant after confounders were considered.

Protective factors

In the adjusted analysis, several factors were negatively associated with relapse, demonstrating independent protective effects. Children who were ever breastfed had 61% lower odds of relapse compared to those who were not (OR: 0.39, 95% CI: 0.24-0.65). This association remained significant in the adjusted model (aOR: 0.47, 95% CI: 0.24-0.95).

In addition, lower odds of relapse were observed in the adjusted analysis among caretakers who received individual IYCF counselling (aOR: 0.29, 95% CI: 0.09-0.73). Conversely, knowledge of key nutrition practices or group participation was associated with increased risk of relapse. Participation in care groups or mother-to-mother support groups was associated with a 70% increase in relapse odds (OR: 1.70, 95% CI: 1.04-2.80). In addition, caregiver knowledge, rather than being protective, was associated with increased odds of relapse. Knowing two or more ways to prevent malnutrition (OR: 2.15, 95% CI: 1.33-3.48), three or more recommended times for handwashing (OR: 2.16, 95% CI: 1.36-3.48), and the recommended breastfeeding duration of 24 months or more (OR: 1.95, 95% CI: 1.18-3.32) were associated with increased odds of relapse. Children of caregivers who cited CMAM services as a source of nutrition information had nearly twice the odds of relapse (OR: 1.99, 95% CI: 1.07-3.74). This association may have been observed as they were more likely to be frequently attending the nutrition facility. These findings highlight the importance of strengthening individual IYCF counselling and personalised recommendations by improving the availability and capacity of community-based nutrition workers, rather than broader knowledge dissemination. This is especially relevant given the current context where counselling might be interrupted due to security, access, or programmatic constraints.

Our findings showed lower odds of relapse among households reporting sufficient quantity of drinking water in the last month (OR: 0.40, 95% CI: 0.23-0.67). The existing evidence base for the relationship between household WASH interventions and relapse is limited and inconsistent (MacCleod et al, 2024). However, our findings suggest that, given the current situation in Sudan, access to sufficient and safe drinking water to prevent relapse should be prioritised.

Risk factors

Households reporting access to land for agriculture had over twice the odds of relapse compared to those without access, even after adjustment for potential confounders such as displacement status (aOR: 2.73, 95% CI: 1.27-6.31). This association could be partially explained by time constraints on the primary caregiver. Previous studies, while not specific to malnutrition relapse, have noted that women’s caregiving capacity is strongly influenced by agriculture workload, leading to suboptimal IYCF practices (Nyantakyi-Frimpong, 2021). This warrants further investigation, as research on the topic is limited. It is also important to consider the increased proportion of cases who were from the host community (62% vs. 38%) when interpreting this finding.

Moderate or severe food insecurity was associated with increased odds of relapse (OR: 2.13, 95% CI: 1.12-4.40), although this relationship was not significant in the adjusted model. The link between household food security levels and malnutrition relapse rates remains uncertain. In a three-country cohort study (summarised in Field Exchange 75), food insecurity has been found to be a risk factor for relapse in certain contexts (King et al, 2025). Relapse was negatively associated with certain socioeconomic assets, including owning a phone (OR: 0.51, 95% CI: 0.29-0.89). Furthermore, control households were less likely to report receiving humanitarian assistance in the last 12 months than relapse cases (OR: 0.29, 95% CI: 0.08-0.81). These trends, although not significant in the adjusted models, perhaps echo the vulnerability of the food-insecure households, in households who have access to limited resources.

Other risk factors included the use of unprescribed medications for treating malnutrition, which more than doubled the odds of relapse (OR: 2.21, 95% CI: 1.18-4.02). Although the association between relapse and use of unprescribed medication is not clear, other studies have reported that use of herbal medicine increases the odds of mortality among children with SAM (Gavhi, 2020). This finding supports the link between suboptimal care practices and increased risk of relapse.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting these results. Despite extensive efforts to ensure the quality of the lists of eligible children, some misclassification of cases and controls is likely. Some relapse cases may have gone undetected if they did not present for treatment, as the study did not include prospective follow-up. The elapsed time between enrolment and interview completion should also be considered in interpreting the findings and may also have introduced potential recall bias. Additionally, the sample size for cases and controls was smaller than anticipated, as not all eligible households were enrolled due to accessibility issues and population movement. Thus, the study may have lacked sufficient power to detect some risk factors.

Households reporting access to land for agriculture had over twice the odds of relapse compared to those without access, even after adjustment for potential confounders such as displacement status (aOR: 2.73, 95% CI: 1.27-6.31). This association could be partially explained by time constraints on the primary caregiver. Previous studies, while not specific to malnutrition relapse, have noted that women’s caregiving capacity is strongly influenced by agriculture workload, leading to suboptimal IYCF practices (Nyantakyi-Frimpong, 2021). This warrants further investigation, as research on the topic is limited. It is also important to consider the increased proportion of cases who were from the host community (62% vs. 38%) when interpreting this finding.

Moderate or severe food insecurity was associated with increased odds of relapse (OR: 2.13, 95% CI: 1.12-4.40), although this relationship was not significant in the adjusted model. The link between household food security levels and malnutrition relapse rates remains uncertain. Food insecurity has been found to be a risk factor for relapse in certain contexts (King et al, 2025). Relapse was negatively associated with certain socioeconomic assets, including owning a phone (OR: 0.51, 95% CI: 0.29-0.89). Furthermore, control households were less likely to report receiving humanitarian assistance in the last 12 months than relapse cases (OR: 0.29, 95% CI: 0.08-0.81). These trends, although not significant in the adjusted models, perhaps echo the vulnerability of the food-insecure households, in households who have access to limited resources.

Other risk factors included the use of unprescribed medications for treating malnutrition, which more than doubled the odds of relapse (OR: 2.21, 95% CI: 1.18-4.02). Although the association between relapse and use of unprescribed medication is not clear, other studies have reported that use of herbal medicine increases the odds of mortality among children with SAM (Gavhi, 2020). This finding supports the link between suboptimal care practices and increased risk of relapse.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting these results. Despite extensive efforts to ensure the quality of the lists of eligible children, some misclassification of cases and controls is likely. Some relapse cases may have gone undetected if they did not present for treatment, as the study did not include prospective follow-up. The elapsed time between enrolment and interview completion should also be considered in interpreting the findings and may also have introduced potential recall bias. Additionally, the sample size for cases and controls was smaller than anticipated, as not all eligible households were enrolled due to accessibility issues and population movement. Thus, the study may have lacked sufficient power to detect some risk factors.

Conclusion

Since April 2023, International Medical Corps has scaled back its services by 33% due to inaccessibility related to security concerns and funding constraints in three states (South Kordofan, Blue Nile, and South Darfur). Therefore, it is crucial to design and implement interventions that prevent relapse to decrease the burden on treatment services and households. Our findings suggest individual IYCF counselling, emphasising the importance of (continued) breastfeeding, access to clean drinking water, and promoting optimal care-seeking behaviour should be prioritised. Strengthening personalised IYCF counselling at community level by community nutrition workers could improve actionable appropriate care practices, decreasing risk of relapse.

Further understanding the relationship between access to land for agriculture and risk of relapse is important. Ensuring households have local access to enough diverse and nutritious foods is of critical importance to prevent malnutrition. Interventions that support the use of available land without negatively impacting optimal care practices may be worth exploring. This is of particular importance in contexts where acute malnutrition services are frequently suspended due to insecurity, shortage of nutrition supplies, and access and funding constraints.

For more information, please contact Iris Bollemeijer at ibollemeijer@internationalmedicalcorps.org.uk

References

Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) (2024) Famine review committee: Sudan, December 2024. ipcinfo.org

Gavhi F, Kuonza L, Musekiwa A et al (2020) Factors associated with mortality in children under five years old hospitalised for severe acute malnutrition in Limpopo province, South Africa, 2014-2018: A cross-sectional analytic study. PloS One, 15(5), e0232838

King S, Marshak A, D’Mello-Guyett L et al (2025) Rates and risk factors for relapse among children recovered from severe acute malnutrition in Mali, South Sudan, and Somalia: A prospective cohort study. Lancet Global Health, 13(1), e98-e111

MacLeod C, Ngabirano L, N'Diaye DS et al (2024) Household-level water, sanitation and hygiene factors and interventions and the prevention of relapse after severe acute malnutrition recovery: A systematic review. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 20(3), e13634

Nyantakyi-Frimpong H (2021) Climate change, women's workload in smallholder agriculture, and embodied political ecologies of undernutrition in northern Ghana. Health & Place, 68, 102536

Stobaugh HC, Mayberry A, McGrath M et al (2019) Relapse after severe acute malnutrition: A systematic literature review and secondary data analysis. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 15(2), e12702

Sudan Nutrition Sector (2024) Nutrition Vulnerability Analysis: Sudan. nutritioncluster.net

Victora CG, Adair L, Fall C et al (2008) Maternal and child undernutrition: Consequences for adult health and human capital. Lancet, 371(9609), 340-357

WHO (2023) WHO issues new guideline to tackle acute malnutrition in children under five. who.int

About This Article

Jump to section

Download & Citation

Reference this page

Bollemeijer I, Majer J, Cherie S, Ahmed AE, Hamid R, Abobaker I, Fadle O & Mustafa N (2025) Risk factors associated with severe acute malnutrition relapse in Sudan Field Exchange issue 75. Emergency Nutrition Network (ENN), Oxford, UK. https://doi.org/10.71744/ht30-pn47