Thriving Together: Improved nutritional outcomes in children with disabilities in Zimbabwe

Svitlana Austin Paediatrician, Sally Mugabe Children’s Hospital, Harare, Zimbabwe

Faith Kamazizwa Nutritionist, Global Cleft and Craniofacial Organisation, Zimbabwe

We would like to acknowledge the Zimbabwean Ministry of Health and Child Care and UNICEF for their generous support for this work. We are also grateful to the SPOON Foundation for sharing their tools and resources to support us in this initiative.

What we know: Children with disabilities face a high risk of undernutrition, with complex needs that make sustained recovery more challenging. In Zimbabwe, no specific interventions currently exist to address the unique needs of children with disabilities.

What this adds: A community outreach intervention can successfully address some of the most immediate needs of children with disabilities, such as inadequate care practices and limited access to treatment for older children with undernutrition. However, additional holistic support is needed, including improved household income and food security to sustain recovery and ensure long-term wellbeing.

According to the Global report on health equity for persons with disabilities, 16% of the global population lives with some form of disability. An estimated 80% of those people with disabilities live in low- and middle-income countries, where access to health, nutrition, and social support services are severely limited and where children with disabilities are among the most vulnerable (WHO, 2022). The exact prevalence of children with disabilities in Zimbabwe is unknown. The most recent survey on the prevalence of disabilities in Zimbabwe, conducted over a decade ago, estimated that 7% of the population live with some form of disability. Additionally, 26% of surveyed households reported having at least one family member with a disability (Ministry of Health and Child Care (MOHCC) & UNICEF, 2013).

Zimbabwe’s strategy on the management of malnutrition aims to address childhood undernutrition by combining hospital- and community-based treatment. Unfortunately, the nutritional guidelines do not highlight the unique needs of children with disabilities. The main treatment for wasting, which is ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF), is primarily designed for children aged 6-59 months with wasting, excluding wasted children over five years old, and those with disabilities. Currently, no alternative treatment or specialised supplement exists for these children. Ideally, families caring for children with disabilities are provided with a comprehensive social support package, including access to appropriate nutritional products, protein-dense foods that are affordable, locally available, and culturally acceptable, and, where possible, cash-based assistance.

Challenges faced in the Zimbabwean context

Children with disabilities in Zimbabwe experience multiple challenges, including medical complications, mental health issues, social exclusion, and limited access to essential services. These difficulties extend beyond the child, placing immense strain on caregivers, often leading to family breakdown, loss of employment, and mental health struggles for parents (particularly mothers).

A major challenge in addressing childhood disability in the country is the lack of effective early identification tools and the absence of a national registry for children born with disabilities. Currently an ‘at-risk’ surveillance system is used to identify infants who may be prone to developmental disabilities. This system flags babies with risk factors such as low birth weight, prematurity, HIV exposure, birth complications, low APGAR scores, severe jaundice or neonatal convulsions. An “at-risk” sticker is placed on their Child Health Card to prompt closer monitoring. However, identification and registration are inconsistent and, in most cases, do not translate into access to additional resources or specialised healthcare services.

Stigma and social isolation of children with disabilities are pervasive, further compounding the difficulties faced by these children and their families. These children and their caregivers are often marginalised and belong to the poorest segments of society. In some cases, fathers abandon their families upon the birth of a child with disabilities, accusing mothers of witchcraft and leaving them to care for their children alone. With full-time caregiving responsibilities, these mothers struggle to secure employment, resulting in significant financial, emotional, and psychological burdens. Children with disabilities are also at heightened risk of violence and abuse, and many mothers fear leaving their children unsupervised, further limiting their ability to work or engage in income-generating activities. Government support for these families is minimal, making daily caregiving extremely difficult, particularly for children who require special feeding, rehabilitation, or assistive equipment.

It is well established that children with disabilities are at great risk of developing undernutrition, while undernutrition, in turn, can exacerbate disability. Feeding difficulties are a major factor causing undernutrition among these children, with 80% of children with disabilities experiencing challenges with feeding (Klein et al, 2023).

A unique community-based intervention

Sally Mugabe Children’s Hospital is one of two central referral hospitals in Harare, for those with severe wasting needing inpatient care. At Sally Mugabe Children’s Hospital, efforts to standardise and improve care have successfully reduced hospital mortality rates. However, clear gaps in care remained for children with neurological disabilities, who accounted for approximately one-third of children admitted to the malnutrition unit. These children experienced longer hospital stays, higher mortality rates, and frequent readmissions due to recurrent episodes of complicated malnutrition. Their caregivers often struggled to manage daily care during extended hospital stays, with little to no support available outside the hospital. Given this, it became clear that, to break this cycle of recurrent hospital admissions, improvements to their care needed to be made.

With assistance from UNICEF and support from MOHCC, the hospital developed a pilot community care intervention to provide a more comprehensive and holistic service for children with disabilities. The initiative targeted high-density areas in Harare. It expanded the already existing rehabilitation team, run by the hospital’s rehabilitation unit, consisting of rehabilitation specialists (physiotherapists, occupational therapists, and rehab technicians) to also include paediatricians, nutritionists, and trauma counsellors. Several teams conducted outreach visits to 12 high-density urban sites in Harare, visiting the same sites every three weeks.

The intervention provided a comprehensive package of care to children with disabilities and their caregivers. Children were enrolled through the hospital’s rehabilitation unit or via self-referrals from the community. The comprehensive package of care included a medical assessment, as well as, where needed, psychological counselling and physiotherapy. The nutritionist would also conduct a growth monitoring assessment on each child. Any child with low weight-for-height or length z-score (WHZ/WLZ) would receive RUTF according to the national guideline, as would children above five years of age with low body mass index-for-age z-score (BMI-for-age). However, it was not always possible to measure a child’s height or length, and low mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) or low weight-for-age z-score (WAZ) was used to assess eligibility for RUTF, in consultation with the paediatrician. Considering compounding challenges that children with a disability face, like difficulty eating and food insecurity, the team recognised that these children required nutritional support beyond the standard age cut-off for wasting treatment of five years.

The nutritionist also led educational group sessions covering essential topics around caring for a child with disability. The sessions were adapted based on materials from the SPOON Foundation. Topics included responsive feeding, safe feeding practices, positioning of children during feeding, improving the nutritional value of foods, identifying cheap, nutrient-dense, locally available foods, and preventing iron deficiency anaemia. Some sessions also focused on caregivers themselves, such as how to deal with stigma and self-care. The same standard package was delivered across all the facilities. When needed, some caregivers would receive one-on-one counselling, which would often include an assessment of feeding and feeding positioning.

The intervention was monitored and evaluated by analysing the anthropometric and medical assessments of the children and as well as through caregivers’ feedback, collected through individual semi-structured interviews, as well as group discussions. This included assessing the acceptability and impact of the intervention on nutritional and rehabilitation needs. To better be able to provide further support, a register of children living with disabilities in the target areas was set up, along with a community support network led by trained lead mothers.

The intervention was implemented with permission from MOHCC, as well as the City of Harare administration.

Findings

Health and nutrition outcomes

A total of 617 children with disabilities, aged five months to 13 years, were enrolled in the programme across 12 participating sites. Of these, 27 (4%) children were aged 0-5 months, 454 (74%) were aged 6-59 months, and 136 (22%) were over five years old. Sessions were held in community halls or local clinics, with attendance varying between visits due to factors such as travel distance and caregivers’ conflicting commitments. Most children in the programme had cerebral palsy (72%), primarily attributed to birth complications, with a smaller proportion linked to neonatal jaundice. Other disabilities included trisomy 21 (“Down’s Syndrome”) (4%) and hydrocephalus (spinal fluid build-up) (3%). Due to limited diagnostic capacity in Zimbabwe, where childhood disability assessments are often based on clinical assessment alone, 21% of children enrolled in the programme did not have an established cause for their disability.

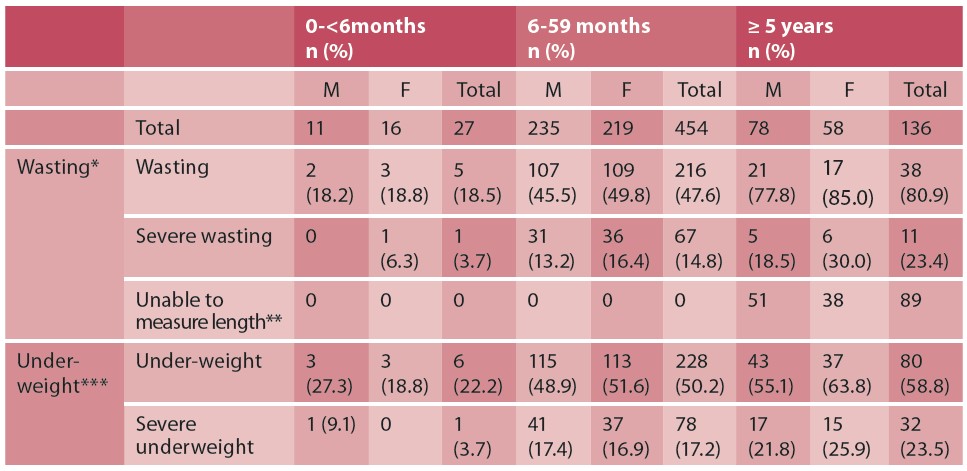

At the onset of the programme, severe wasting was identified in 15% of the children and moderate wasting identified in 34% (see Table 1). Height or length measurement was not possible in 89 (65%) of the children aged above five years due to presence of contractures (stiffness of limbs). However, weight measurement was possible in all enrolled children, and so underweight was also used as a criterion for RUTF. 51% of children enrolled in the programme were underweight, highlighting the high prevalence of undernutrition in these children. The breakdown by age category showed: 22% among infants aged 0-6 months, 50% among children aged 6-59 months, and 59% among children aged above five years were underweight. Among all age categories, underweight and wasting was slightly more prevalent in girls compared to boys, except underweight in infants aged 0-6 months, where 27% of boys were underweight compared to 19% of girls.

Table 1. Nutrition status of children on enrolment into the programme

Over half of caregivers reported feeding difficulties in their children, including choking on feeds, regurgitation, and difficulty tolerating age-appropriate textures. Inappropriate feeding practices were frequently observed, such as force-feeding and unsafe feeding positions. Additionally, the quality and nutrient density of provided meals was often inadequate, with children frequently given diluted porridge or maize-based drinks, under the assumption that they would be unable to tolerate other foods.

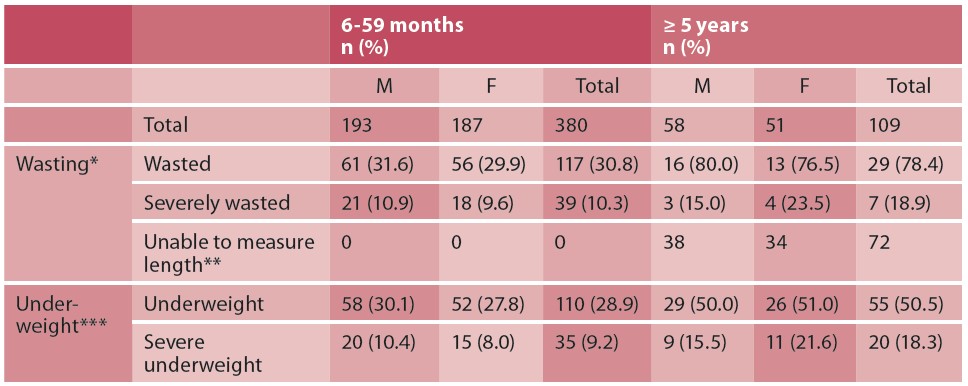

Of the 617 children enrolled, 489 were included in the final analysis at the end of the intervention (see Table 2). Over the course of the intervention, improvements in undernutrition rates were observed. The proportion of children with underweight, combining all age categories, declined from 50.9% on enrolment to 33.7% at the end of the intervention and for severe underweight from 18.0% to 11.0%. However, despite the progress, a significant number of children remained undernourished after a year in the programme, highlighting the ongoing need for sustained nutritional and caregiving support.

Table 2. Endline data on children enrolled in the programme that were measured at baseline

Impact on caregiving practices

Through caregiver feedback it was found that the programme was well received by both the caregivers and their children, with most parents reporting greater confidence in looking after their children following the intervention. Caregivers gained a better understanding of their children’s nutritional needs and learned how to enhance meal quality using affordable, locally available foods. This led to improved feeding practices and more enjoyable mealtimes for both children and their caregivers.

Lessons learned

This initiative was able to fill a major service gap for children living with disabilities in the targeted communities in Harare. Support for this group has traditionally been fragmented, often relying on non-governmental organisations rather than a structured government service. By integrating this initiative with the existing rehabilitation outreach programme, it was possible to provide support despite a limited budget. This small pilot project demonstrated that both the nutrition status of disabled children and caregiving practices can be improved through a coordinated effort to address different aspects of their needs.

However, there were also some challenges in the implementation of this intervention. For example, many caregivers skipped sessions due to conflicting commitments. Some children with feeding difficulties had issues with consuming RUTF due to swallowing difficulties, and alternatives were not available. There was also limited access to medications, requiring referrals to local health centres rather than direct provision. Many of the children continued to have feeding challenges in food-insecure households and sharing of RUTF within the household was common. One potential improvement could be the provision of additional nutritious food options for children unable to tolerate RUTF, ensuring they still receive adequate dietary support. The initiative also highlighted the need for validated approaches to identify children with disabilities causing contractures. WAZ could potentially be used for this, but further research is needed.

Conclusion and recommendations

Children with disabilities and their families can greatly benefit from community-based interventions providing coordinated multidisciplinary support services. This should include early screening and diagnosis, followed by a comprehensive care package in early childhood and ongoing support for caregivers to promote better care practices and social inclusion. To maximise impact, this community care model should be expanded to other urban centres in the country. This requires strong collaboration and buy-in from the relevant government departments, including MOHCC, the Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare, and the Ministry of Education to ensure sustainability and integration into national policy frameworks. Sadly, due to the recent global funding cuts, it appears that funding for this initiative may be limited in the future while MOHCC focuses on identifying funding for critical HIV and tuberculosis treatment services. Going forward, services for children with disabilities are unlikely to be prioritised, highlighting the vital need for sustainable solutions to support these vulnerable children.

For more information, please contact Svitlana Austin at dr.svitlana.austin@gmail.com

References

Klein A, Uyehara M, Cunningham A, Olomi M, Cashin K, Kirk CM (2023) Nutritional care for children with feeding difficulties and disabilities: A scoping review. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2023 Mar 17;3(3)

MOHCC and UNICEF (2013) Living conditions amongst persons with disability survey 2013: Key findings report.

WHO (2022) Global report on health equity for persons with disabilities. who.int

About This Article

Download & Citation

Reference this page

Austin S & Kamazizwa F (2025) Thriving Together: Improved nutritional outcomes in children with disabilities in Zimbabwe. Field Exchange issue 75. Emergency Nutrition Network (ENN), Oxford, UK. https://doi.org/10.71744/ets5-8b35