Integrating complementary food supplements at scale into national nutrition programmes: Insights from India

Purnima Menon is a senior researcher with the International Food Policy Research Institute’s South Asia Regional Office in India.

Shariqua Yunus Khan is a medical doctor and public health practitioner managing the nutrition portfolio with the World Food Programme, India Country Office.

Rajan Sankar is with The India Nutrition Initiative (TINI) of the Tata Trusts, India

Background

Every year 27 million babies are born in India. At any time, there is a cohort of over 50 million children under two years old. Good nutrition during the first two years helps to build bodies, brains and immunity for every child; yet, survey after survey tells us there is a real crisis in how babies across India are fed, especially around complementary feeding. Indeed, barely a tenth of Indian babies received a minimally adequate diet, even in 2018.

Feeding babies well is no small task. Multiple times a day, every day, parents and caregivers must prepare, feed and clean their infants – adding up to an estimated 5,000 feeding moments in the first two years of life. Parents and caregivers need information, time, resources, skills and support to undertake what is a massive caregiving task over these first two years of a child’s life.

Public programmes implemented by frontline health workers and medical professionals typically offer parents advice and information, with research finding varying degrees of impact. Indeed, programmes to provide breastfeeding and complementary feeding information and support to families are a common feature of public policy across South Asia. However, few countries in the region also offer families with young children specially formulated complementary food supplements – fortified cereals, cereal-pulse mixes, eggs – to support infant feeding. Evidence suggests that, in food-insecure populations, either food or cash should be provided to families to support infant feeding1. India and Sri Lanka are two of the countries in South Asia that include public provisioning of complementary foods in their nutrition programmes at national scale.

India’s Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) programme

India’s flagship nutrition programme, the ICDS programme, is the world’s largest community-based nutrition programme focusing on pregnant and lactating women and children under six years of age. Fuelled by the work of over 1.4 million Anganwadi workers, the programme provides a range of services at community-based centres (Anganwadi centres). These services include food supplementation, provided either as take-home food rations or as hot cooked meals, depending on the programme client. Other services provided include growth monitoring, behaviour change communication activities through community-based events at the centres, and home visits by the workers for nutrition counselling, as well as linkages and referrals within the health system.

A breastfeeding mother in Narharpur Block, Chhattisgarh, receives take home rations prepared by women from self-help groups. ©Shawn Sebastian, IFPRI

A breastfeeding mother in Narharpur Block, Chhattisgarh, receives take home rations prepared by women from self-help groups. ©Shawn Sebastian, IFPRI

The programme began in 1972 as a pilot and today is a nationwide programme that has scaled up tremendously in the last 15 years, following a legal act that linked ICDS with the right to food and a range of programme and policy efforts related to nutrition2. It has been challenging to assess the impact of ICDS on nutrition outcomes, but evidence suggests that programme expansions and coverage have contributed to declines in stunting in several states. As of 2016, use of the programme is still highly variable across states; however, in some, close to 90% of the population use the programme services.

Provision of CF supplements

India’s experiences with scaling up the provision of complementary food supplements in the ICDS programme over the last 10-15 years offer lessons on a range of issues, including composition, production models, governance, financing, and reach and uptake. Based on recent reviews3, 4and a range of stakeholder discussions, we explore each of these briefly below:

- Composition. Food supplements in the ICDS programme were initially formulated to close calorie and protein gaps and updates to the composition have been incremental over the years. Composition guidance has not separately examined the needs of children 6-24 months of age versus those of children above two years of age. Today, with updated scientific evidence on nutritional needs of infants during the period of complementary food supplementation, it is time for India to review and revise composition guidance. In addition to updating guidance on the needs of infants, composition guidance needs to consider the high levels of sugar in the current composition; the average energy contribution from sugar is about 23% of total calories. Additional composition guidance also needs to consider the role of quality protein; milk/milk powder is included in the formulation of only about 25% of products for young children. Some states in India have explored the inclusion of eggs, along with cereal-based complementary food supplements, thus improving the quality of protein in the supplementary foods.

- Production models. Across India, a range of production models for complementary food supplements have been explored. Partial financing for the programme is provided by the central government to states, which contribute their own funding and adopt their own models of production of the food supplements. In some states, these are produced by state-run production companies; in others, they are produced by women’s self-help groups, who receive contracts from the states; in yet others, frontline health workers receive cash to their bank accounts and procure and produce the food supplements. Each model has its pros and cons. The choice of the production model is ultimately made at the state-level.

- Governance. On governance, a range of insights are available on how the production models have played out. Lack of accountability mechanisms, corruption at multiple levels and poor food safety are concerns that have been documented5. All these seem to be prevalent in both centralised and decentralised self help group models. Efforts to improve accountability, regardless of the production model, must therefore be a central component of strengthening the quality and reach of the supplements. Similarly, mechanisms to test and ensure quality of supplements are highly variable across states, but these must be a key part of the overall governance mechanism.

- Financing. A key consideration is available domestic and development partner financing to cover all the costs of producing and delivering the food supplements to the last mile. In the ICDS programme, a majority of the national budgets for the nutrition programme go towards the food supplements, yet there are shortfalls that stem from either financial allocation gaps or fund-utilisation gaps at the state level6.

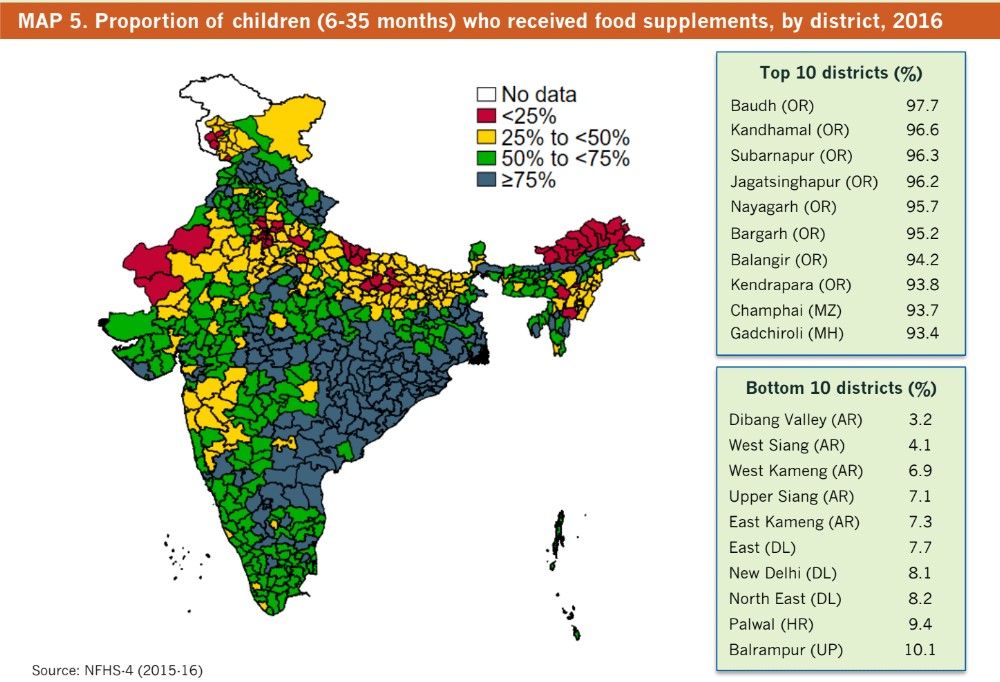

- Reach and uptake. Research indicates that, regardless of the production model, the overall reach of the food supplements is highly variable, ranging from barely 3% in some districts to over 95% in others7. A critical insight from research on the reach of the supplements is that reach is generally higher in the poorer, but not the poorest, quintiles than among the upper quintiles. This could be due to placement bias; i.e., because the ICDS programme expanded into poorer geographic areas. It could also be due to selection bias at the household level: families who felt a need for additional nutritional or food support accessed the programme more. In either case, the higher coverage in these groups implies a felt need for the programme. Unfortunately, research on coverage also shows that states with the largest number of undernourished children in India, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, are also those where the largest number of children are missed by the programme. Coverage is lowest in these states and much more effort is needed to increase the reach of the programme and use of the food supplements.

Missing evidence

Unfortunately, a missing piece of evidence in the context of India’s programmes is how client populations perceive the food supplements and the programme, and how they integrate the food supplements into the daily diets of their infants. Little is known about whether client populations value the food supplements, whether they fit their cultural norms of what infants should consume, whether they feel they are safe to feed their infants and, last, but not least, whether they can easily integrate a publicly provided food supplement into their daily routines. Contrast this with the availability of evidence from Mexico’s nutrition programme, which successfully integrated high-quality food supplements and behaviour change into the programme through careful research that listened to client populations.

Recommendations for improving the complementary food supplements

What does the evidence and experience to date imply for how India, and other countries in the region, should consider the role of complementary food supplements in their national nutrition programmes?

First, in food-insecure populations, and especially in the context of the food insecurity that is anticipated as a result of the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, complementary food supplements can play an important role in supporting parents with infant feeding. Indeed, studies suggest that appropriately formulated food supplements or high nutrient quality foods such as eggs, contribute critical nutrients without displacing breastmilk. Countries that aim to integrate these into national programmes should certainly explore whether client populations need additional food supplements to support infant feeding. Cash transfers could be explored as well, with the caveat that evidence across the region is still mixed.

Second, even as countries consider adding complementary food supplements to the programmes, or consider updating their policies and programmes, attention is needed to issues of nutritional composition and to the range of programmatic, governance and financial arrangements that affect programme reach. These affect the translation of policy guidance and intent into actual food supplements in the hands of client populations and therefore need as much, if not more, care and attention.

Third, food supplements are certainly not enough; efforts to strengthen the integration of food supplements with ongoing behaviour change communications and/or counselling elements of the programme are vital to help families use the supplements appropriately, ensuring that they do not displace breastmilk or other family foods.

Finally, a continuous learning agenda that builds on ground-up research and listens to client populations is central to ensure that food supplements meet nutritional needs and food safety standards and are culturally acceptable. Families with young children bring valuable insights on programmatic features regarding the taste and acceptability of the supplements and on their integration into the diets of their infants. Listening to the parents of young children across India – and, indeed, all of South Asia – is important to ensure that the millions of dollars that go into nutrition programmes will drive impact.

Footnotes

1Bhutta et al. (2008). What works? Interventions for maternal and child undernutrition and survival. The Lancet, 371(9610), 417-440.

2Chakrabarti et al. (2019). India’s Integrated Child Development Services programme; equity and extent of coverage in 2006 and 2016. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 97(4), 270.

3Vaid et al. (2018). A review of the Integrated Child Development Services’ Supplementary Nutrition Programme for Infants and Young Children: Take home ration for children. POSHAN Research Note. Intl Food Policy Res Inst.

4World Food Programme. (2019). Review of Take-Home Rations under the Integrated Child Development Services in India. New Delhi, India: World Food Programme, India.

5Saxena, N. C., & Srivastava, N. (2009). ICDS in India: policy, design and delivery issues. IDS Bulletin, 40(4), 45-52.

6Chakrabarti et al. (2017). Achieving the 2025 World Health Assembly targets for nutrition in India: What will it cost? (Vol. 2). Intl Food Policy Res Inst.

7Avula et al. (2018). District-level coverage of interventions in the ICDS scheme during pregnancy, lactation and early childhood in India: Insights from the National Family Health Survey-4 (No. 4). IFPRI.