Experiences of the Integrated Management of Acute Malnutrition (IMAM) programme in Nepal: from pilot to scale up

Click here to listen to an interview with one of the authors on the ENN podcast channel

By Karan Courtney Haag, Anirudra Sharma, Kedar Parajuli, and Anju Adhikari

Karan Courtney-Haag is Chief of Nutrition for UNICEF Nepal Country Office.

Anirudra Sharma is a Nutrition Specialist for UNICEF Nepal Country Office.

Kedar Raj Parajuli is Chief of the Nutrition Section, Family Welfare Division, Department of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Population Nepal.

Anju Adhikari is a UNICEF Nutrition Consultant, Nutrition Section, Family Welfare Division, Department of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Population Nepal.

Location: Nepal

What we know: Despite falls in the prevalence of stunting in children, wasting remains a persistent problem in Nepal, a country prone to emergencies.

What this article adds: A combination of a persistently high wasting prevalence, advocacy efforts by United Nations (UN) agencies and development partners and the need to respond to severe and recurrent humanitarian crises catalysed an initial pilot Community-based Management of Acute Malnutrition (CMAM) programme in Nepal in 2009 to test delivery models within existing health services. Ten years later, a sustainable scale up of the integrated management of acute malnutrition (IMAM) has been achieved through a government owned and managed approach enabled by a strong policy framework (embedded within the Multi-sectoral Nutrition Plan), national and devolved governance architecture, commitment and dedicated financing and services integrated within a well-developed community health system. The Ministry of Health and Population (MoHP) now funds 90% of the IMAM programme. Technical and financial assistance from United Nations agencies, bilateral donors and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) have enabled the evolution of the IMAM programme. Owing to its success, IMAM was scaled up to cover 38 of 77 districts across the country with capacitated and skilled government health workers delivering care. Surge capacity to emergencies is embedded as part of emergency preparedness. Ongoing challenges being addressed include the supply chain management of ready to use therapeutic food (RUTF), case identification, treatment coverage (low at 15%) and the management of moderate wasting.

Context

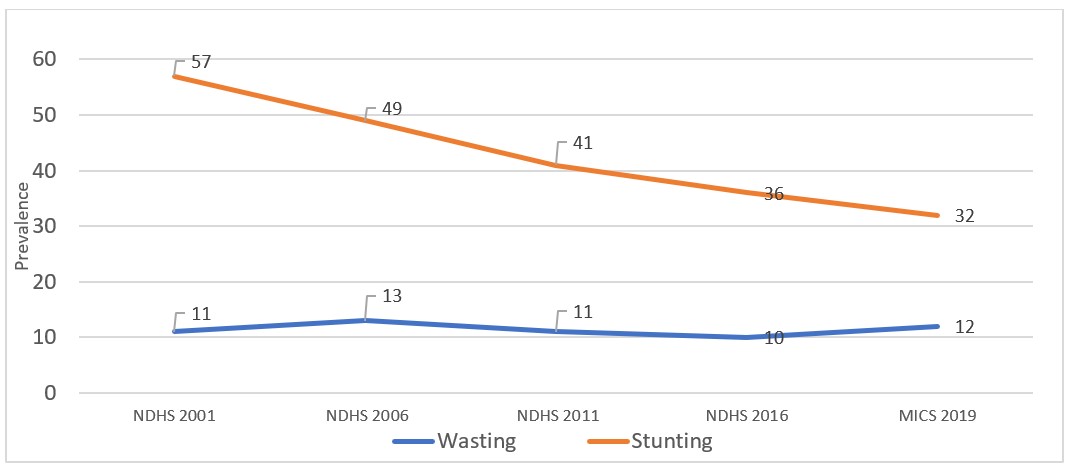

Improving the nutritional status of children under five years of age is a major challenge in Nepal. The prevalence of stunting in children has steadily decreased over the past 16 years from 57% in 2001 (Nepal Demographic Health Survey (NDHS) 2001) to 32% in 2019 (Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) 2019). However, the prevalence of wasting has remained almost the same, currently standing at around 12% nationally (Figure 1). An estimated 3% of children under five years of age are severely wasted, equivalent to 54,000 children (MICS, 2019). The high national prevalence of wasting masks geographic, ethnic, socio-economic and age disparities across Nepal’s seven provinces that are reflected in varying wasting levels, from 17.6% in Karnali Province in the far west to 4.7% in Bagmati Province in central Nepal.

Figure 1: Trends in the prevalence of wasting and stunting among children under five years of age in Nepal

NDHS = Nepal Demographic Health Survey

MICS = Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys

Nepal’s malnutrition crisis is the result of multiple causes and factors including household socio-economic status, sub-optimal breastfeeding practices, recurrent childhood illnesses, poor complementary feeding practices and underlying poor sanitation and environmental conditions. These issues are exacerbated by the impact of severe and recurrent humanitarian crises in the country including annual floods in the southern provinces and districts of Nepal and topographic challenges in other parts of the country that lead, for example, to lack of access to essential services in hilly and mountainous areas.

Prior to the introduction of community-based management of acute malnutrition (CMAM) in Nepal, the treatment of acute malnutrition was carried out mainly in Nutrition Rehabilitation Homes (NRHs) established since 1998 by the Nepal Youth Opportunity Foundation (NYOF),1 an international non-governmental organisation (INGO), managed by the Ministry of Health and Population (MoPH) and staffed by government health workers. Assistance to families of wasted children focused mainly on caregiver counselling on hygiene, feeding practices and balanced diet and treatment with therapeutic milk (prepared according to the World Health Organization (WHO) recipe) and nutrient-dense food. Severely wasted children were treated as inpatients at NRHs where they and their caretaker were expected to stay for a minimum of four weeks. This posed difficulties for caretakers in terms of care for other children and work responsibilities, leading to a high default rate. In addition, the NRHs could not address severe wasting on a large scale due to their limited number (14) and the low capacity of each NRH nutrition unit (10 to 20 beds).

In March 2007, the WHO, the World Food Programme (WFP), the Standing Committee on Nutrition (SCN) and United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) released a joint global statement in support of CMAM which recognised that large numbers of severely wasted children could be treated in their communities without being admitted to a health facility or a therapeutic feeding centre. This gave impetus to the Government of Nepal to implement CMAM programming, the evolution of which is described in this article.

Building the evidence for CMAM in Nepal – pilot study and evaluation 2009-2012

UNICEF and the Ministry of Health and Population (MoHP) in Nepal carried out a study in 2008 to assess the feasibility of implementing CMAM (known as Community Therapeutic Care at that time). The study confirmed that there was sufficient capacity in Nepal to pilot a CMAM programme within the existing health system through government hospitals, health post staff and female community health volunteers (FCHVs) in collaboration with the national and district health authorities. The pilot programme was subsequently approved for implementation by the Government of Nepal in 2008 and included in the National Emergency Nutrition Policy.

The purpose of the pilot was to evaluate the integration of CMAM programming within the existing government health system in the three different agro-ecological zones of the country (terai in the south and the hill and mountainous regions). Five pilot districts were selected across the three zones due to their high prevalence of wasting (>10%), widespread poverty, hospital infrastructure and existing capacity for Community Based Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (CBIMCI). A baseline nutrition survey was undertaken in all five pilot districts by Action Contre la Faim (ACF) and Concern Worldwide.2 Three different operational models to treat severe wasting were then tested in the five pilot districts. In model one, Concern Worldwide, an international non-governmental organisation (INGO), provided technical and financial assistance to government health personnel to implement the CMAM programme in one district. In model two, UNICEF provided direct financial support and technical assistance to the central government who, in turn, allocated funds to two districts for implementation of the CMAM activities. In model three, a local non-governmental organisation (NGO) supported the capacity development of district and provincial health officers with remote technical support from UNICEF and the Ministry of Health and Population (MoHP). The pilot was funded by the government, the UK Department for International Development (DFID), UNICEF, the European Union (EU) and the Central Emergency Response Fund.

By the end of the pilot, 75 outpatient therapeutic centres (OTCs) had been established in the five pilot districts. Most of the OTCs were located in a room or building in a primary health centre (PHC), hospital or health post (HP) and, in a few cases, OTCs were implemented in a sub-health post (SHP). OTCs were staffed by existing government health workers who were trained on the CMAM protocol. These were typically nurses who were seconded from their normal work posts and services and who provided services free of charge to the programme. Ready to use therapeutic food (RUTF) was used to treat severely wasted children without complications, sourced by development partners and managed by the MoHP outside of the health supply chain system.

In 2011, UNICEF supported the MoHP to conduct an evaluation to assess the performance of the CMAM pilots (UNICEF, 2012). The evaluation demonstrated good performance with respect to Sphere indicators in all five pilots. As of June 2011, out of 5,609 discharged children, 86% recovered, 0.2% died and 9% defaulted (Table 1). The average length of stay was 49 days and the average weight gain was 4.8g/kg/day. Treatment coverage was not calculated. The evaluation found that model two, direct support from UNICEF to the government, was the most cost-efficient modality and the model that fostered strongest government ownership of the programme. The lessons and recommendations from the pilot evaluation were used by national stakeholders, United Nations agencies, donors and NGOs to advocate for the allocation of resources for the scale up of CMAM in areas of Nepal with high wasting burdens.

Table 1: Total severe acute malnutrition (SAM) treatment in Nepal (2009-2018)

Facilities | Admission | Discharged | Recovered* | Deaths* | Defaulter* | Other discharged* |

Outpatient (OTC) | 82,923 | 66,439 (80.1%) | 55,274 (83.2%) | 176 (2.6%) | 7,214 (10.9%) | 3,755 (5.7%) |

Inpatient (NRH) | 17,076 | 17,076 (100%) | 16,588 (97.1%) | 7 (0.04%) | 0 | 481 (2.8%) |

Total | 99,999 | 83,515 | 71,862 | 183 | 7,214 | 4,236 |

% | 83.5 | 86.0 | 0.2 | 8.6 | 5.1 | |

* % of discharged

Integration of CMAM into Primary Health Care Services

Policy framework

The success of the pilot was the trigger for the introduction of Nepal’s CMAM programme across six out of seven provinces across the country, selected on the basis of their nutritional vulnerability. At this point, the programme was transformed into the Integrated Management of Acute Malnutrition (IMAM) - a term that encompasses the intention to further integrate facility and community-based approaches as well as prevention and treatment services. In 2013, national IMAM guidelines were developed by the Ministry of Health and Population (MoHP) and the IMAM programme was included in the country’s first Multi-sectoral Nutrition Plan (MSNP-I, 2013-2017). This was a significant step forward, reflective of the government’s increasing commitment to the programme and the nutrition agenda and recognition of the need to embed CMAM programming within wider treatment and prevention services. In 2018, the second edition of the MSNP (MSNP-II, 2018-2022) was finalised and approved which also prioritised IMAM for the health sector. The MoHP is the overall lead ministry for nutrition specific interventions within the MSNP, including CMAM programming, and is accountable to the High-Level Nutrition and Food Security Steering Committee which sits within the National Planning Commission. The National Health Policy, National Health Sector Strategy and IMAM guidelines are other important policy and technical documents that drive the IMAM programme in Nepal.

Accountability and funding

At provincial level, the Ministry of Social Development (MoSD) is responsible for implementing nutrition specific interventions developed by the MoHP and health facilities are responsible for implementation at municipal level. However, since the federalisation of Nepal, all three tiers of government (federal, provincial and local) are independent, therefore the MoSD is not accountable to, nor does it report to, the MoHP for this implementation.

The IMAM programme was initially funded by development partners, including UNICEF. However, the MoHP now funds 90% of the programme and the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID) and the World Bank support the remaining 10%. Government funds include the procurement and management of therapeutic food and milks within the health system’s supply chain, staffing, training of the government health workforce and information management. UNICEF, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and Action Contre la Faim (ACF) provide ad hoc support for capacity development activities on request from the MoPH and UNICEF has supported ready to use therapeutic food (RUTF) procurement when the government process has been delayed or constrained. A five-year costed action plan for nutrition is currently being developed by the MoHP which will inform the exact costs of the IMAM programme.

CMAM implementation modality

IMAM is delivered through the government health system as a part of a comprehensive set of nutrition interventions, integrated within the basic package of health services. At municipal level, IMAM is delivered at government health facilities through a separate room or desk alongside other child health and nutrition programmes, all of which serve as platforms for identifying children with moderate or severe wasting. Children attending a health facility for growth monitoring and infant and young child nutrition counselling or for the integrated management of childhood illnesses (IMCI) are screened using weight for height and, if severe wasting is indicated, are referred for treatment in either an outpatient therapeutic centre (OTC) or a Nutrition Rehabilitation Home (NRH) depending on whether complications are present. When a child is identified as moderately wasted, their caregiver is given nutrition counselling.

Female community health volunteers (FCHVs) also screen children using mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) during the biannual vitamin A campaigns, distribution of micronutrient powders and during village-level mothers’ groups and nutrition education activities. When children are referred to a health facility for nutrition assessment and subsequent treatment, those who are not yet included in the government’s universal child cash grant are identified and referred for registration.

Performance indicators

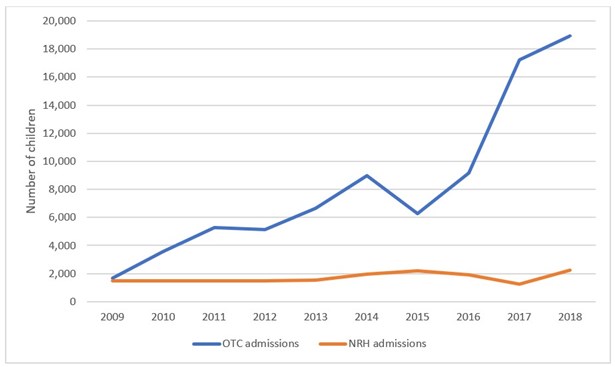

Since 2012, the IMAM programme has expanded and is now implemented in 38 out of 773 districts through 500 OTCs located in health posts and 21 NRHs located within hospitals. Figure 2 shows the increase in admissions of severely wasted children to OTCs between 2009 and 2018 as the programme expanded into new districts and the number of OTCs increased. The increase in admissions was also due, to some degree, to increased social mobilisation efforts and media campaigns promoting the services as well as the increased capacity of health workers to identify and treat severely wasted children. The drop in admissions in 2015 shown in Figure 2 is likely due to the immediate disruption in services caused by the earthquake that occurred resulting in the loss of healthcare infrastructure and reduced capacity for service provision. OTC indicators between 2009 and 2018 show high performance including an average recovery rate of 83%, a low death rate of 0.26% and a defaulter rate of 10.9%, well within Sphere standards.

Figure 2: Admissions to OTCs and NRHs between 2009 and 2018

Barriers and bottlenecks

The continued high prevalence of wasting indicates that there is a need to give greater priority to actions to prevent children from becoming wasted. Currently there is more emphasis on the treatment of wasting and very little is understood about actions to prevent it within the Nepal context.

Despite the successful scale-up of the IMAM programme in Nepal, there are barriers to coverage and quality of services that still need to be addressed. Active case finding through the health system is weak with screening linked to two mass vitamin A campaign events per year, the reach of which is limited and constrained by topography and access issues. Outside of the vitamin A campaigns, FCHVs are not systematically or routinely screening children for wasting, for example at the time of admission for other child related issues. This is a missed opportunity for the detection and referral of children in need of treatment. On the demand side, caregiver recognition of wasting is very low. Parents and caregivers often do not recognise the signs of wasting among their children, nor do they know about the associated increased risk of morbidity or mortality. Weak case finding and low demand by caregivers results in poor early detection and referral and health seeking for treatment.

Another barrier to improved treatment is weaknesses in the government supply chain management system. Stock outs at health facility level of RUTF or therapeutic milks are too frequent and the loss of stock due to expiry is linked with low detection rates and treatment defaulting. The MoHP is set to address these bottlenecks by first revising the national guidelines to include ‘family MUAC’ or ‘mother-led MUAC’ to enable caregivers to screen their own children for wasting and hence trigger early detection and care seeking. Supply chain issues are systemic and will require increased financial and human resource investment by MoHP to resolve. Another barrier is the lack of treatment for children with moderate wasting. Currently, caregivers of children identified as moderately wasted are counselled on feeding, hand washing, sanitation and hygiene practices. The MoHP is currently considering a change to the national IMAM guidelines to include a treatment option that would also encompass moderately wasted children, either through the provision of supplementary food and/or a change to a simplified wasting management protocol. This would help to prevent children with moderate wasting slipping into severe wasting.

More recently, the MoHP with support from development partners, has adapted the national IMAM protocol in light of the restrictions imposed as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Adjustments include follow up visits having been extended from one week to two weeks and the MoHP is considering including family-MUAC in the revised version of the guidelines.

Lessons learned implementing IMAM in Nepal

The following are some of the lessons learned and factors contributing to the success of the IMAM programme in Nepal and areas that require more attention:

National policy framework: The IMAM programme is included in national policy and plans, including in the first Multi-sectoral Nutrition Plan (MSNP-I, 2013-2017) and its successor, MSNP-II, 2018-2022, as a high priority programme. Similarly, it is reflected in the national health policy and national health sector strategy and implementation is supported by national IMAM guidelines. The most recent National Nutrition Strategy and the Ministry of Health and Population (MoHP) five-year costed action plan also includes the IMAM programme. These policy documents form the foundation on which the programme is managed and implemented in Nepal.

Well-established nutrition governance architecture and financing commitment: After the formulation of MSNP-I in 2013, nutrition governance architecture was established at all levels of government. Nutrition and food security steering committees and coordination committees at federal, provincial and local government levels are responsible for planning, budgeting and ensuring funds are allocated for nutrition programmes. Without these, the IMAM programme would not have received the funding necessary for it to evolve.

Well-established community health system: In every ward of local government, there is at least one health facility consisting of five to eight health workers. In each community, there is one mothers’ group led by a female community health volunteer (FCHV). These health workers, mothers’ groups and FCHVs have the knowledge and skills to support community-based nutrition programmes including IMAM. The FCHVs screen children for wasting using mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) and facilitate and strengthen the referral linkages between village and health facility.

Commitment and ownership of different tiers of governments: Local governments across Nepal have declared their commitment to eliminate all forms of maternal, adolescent and young child malnutrition through a multi-sectoral approach. Provincial and local governments have included nutrition programmes with budget allocation in their annual work plans and budgets so they can realise their respective commitments for universal coverage of essential nutrition services including the IMAM programme. While UNICEF continues to provide technical assistance, the Government of Nepal has since allocated domestic resources for the procurement of ready to use therapeutic food (RUTF), capacity development of healthcare providers and a commitment to fulfill its scale up plan for sustainable continuity of the programme.

Procurement and supply of RUTF: For the last five years, the MoHP has gradually assumed responsibility for procuring RUTF and therapeutic milks using domestic resources, with development partners no longer providing this support. Despite this positive step to full government ownership, the allocated budget from government is not yet sufficient to meet 100% of the needs of severely wasted children in Nepal. There is an intention by MoHP to include RUTF in the Essential Medicine list in Nepal which may facilitate increases in allocated funds to meet the full need. Additionally, there are times when MoHP requests UNICEF to fill supply gaps that arise due to lengthy delays in the government’s procurement processes. This requires further attention. Since local production is not financially feasible in Nepal, supplies are currently imported from India.

Technical assistance to MoHP: The technical and financial assistance provided by UNICEF, the European Union, the Department for International Development (DFID), Action Contre la Faim (ACF) and Concern Worldwide to the MoHP over the past decade has helped to guide and steer the evolution of the IMAM programme and take a health system strengthening approach. Partners to the MoHP are still supporting in-service training of healthcare providers, capacity development of FCHVs, technical guidance for supply chain management, programme monitoring and reporting and periodic programme reviews and, most recently, the revision of the national IMAM guidelines.

Coverage gaps: Whilst there has been good progress in scaling up the IMAM programme to 38 out of 77 districts in Nepal and the establishment of outpatient therapeutic centres (OTCs) and Nutrition Rehabilitation Homes (NHRs) within the health system, the treatment coverage remains low at approximately 15%. More attention is needed to increase active case finding and the referral of severely wasted children so that more children who need it receive treatment.

Capacity for surge support in emergencies: Humanitarian crises have also played a critical role in the evolution of CMAM/IMAMcommunity-based management of acute malnutr programming ition (CMAM)/IMAM programme in Nepal. There have been multiple humanitarian crises that the government has responded to over the past decade, each of which has strengthened the resolve of the MoHP to scale up and fully integrate the IMAM programme into its overall nutrition programme. The capacity development of healthcare workers, FCHVs and civil society organisations that occurred during the pilot phase and capacity for surge support to respond to each humanitarian crisis (earthquake, drought and floods) has contributed to a pool of skilled providers. The implementation of the IMAM programme during these emergencies also provided evidence to the government of how well the IMAM programme worked to save lives in a humanitarian context.

Implementation of the IMAM programme has also contributed to the government’s improved emergency preparedness and response capacity whilst the programme surge approach due to multiple crises has also helped to scale up IMAM from the initial five pilot districts to 59 between 2006 and 2018. Those districts supported during the earthquake emergency were subsequently phased out because of the declining need and, as of 2020, the IMAM programme is being implemented in 38 out of 77 districts.

Conclusions

The IMAM programme is Nepal has been scaled up to improve coverage of wasting treatment using a government owned and managed approach, enabled by a strong policy framework, national and devolved governance architecture and financing commitment, with services integrated within the national health system. Owing to its success, IMAM is now delivered at scale in 38 districts across the country with capacitated and skilled government health workers delivering care. While continuing to develop existing services, the next critical step for the Ministry of Health and Population (MoHP) is to address how to manage children who are moderately wasted considering new ways such as simplified approaches to treatment and, equally important, to invest in understanding and implementing actions that prevent wasting.

For more information please contact Anirudra Sharma.

References

Ministry of Health [Nepal], New ERA, and ORC Macro. 2002. Nepal Demographic and Health Survey 2001. Calverton, Maryland, USA: Family Health Division, Ministry of Health; New ERA; and ORC Macro.

Ministry of Health, Nepal; New ERA; and ICF. 2017. Nepal Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Kathmandu, Nepal: Ministry of Health, Nepal.

UNICEF (2012) Evaluation of Community Management of Acute Malnutrition (CMAM): Nepal Country Case Study. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/evaldatabase/index_69858.html

UNICEF 2012. Evaluation of Community Management of Acute Malnutrition (CMAM). Nepal country case study. UNICEF Evaluations Office, July 2011. (11)

WHO, 2007. Integrated-based Management of Severe Acute Malnutrition: A joint statement of the World Health Organization, World Food Programme, United Nation System Standing Committee on Nutrition and United Nations Children’s Fund, Geneva, World Health Organization.

1 https://www.nepalyouthfoundation.org

2 Nutrition Anthropometric Survey, Mugu, Achham, Kanchanphur ACF, 2008; Nutrition Survey Report, Jajarkot, Sustainable Development Initiative report to Concern, 2008.

3 The number of districts in Nepal increased from 75 to 77 in 2017 due to federalisation